Aubert Lemeland and Lennox Berkeley

Allan Clive Jones remembers French composer Aubert Lemeland and his admiration of Lennox Berkeley’s music.

Aubert Lemeland was born on 19 December 1932 at La Haye-du-Puits, on the Cherbourg peninsula. Shortly after his birth, his mother, a generous, gentle, musical woman, died of a heart attack, and before long his father married her younger sister. According to Lemeland, his stepmother was authoritarian, dominating and materialistic and he did not warm to her. Respite from familial discontent was found in music, initially through 78 r.p.m. discs of popular classics, and later through the piano and printed music that had belonged to his mother. He soon became a keen score-reader, despite finding piano lessons and solfège boring.

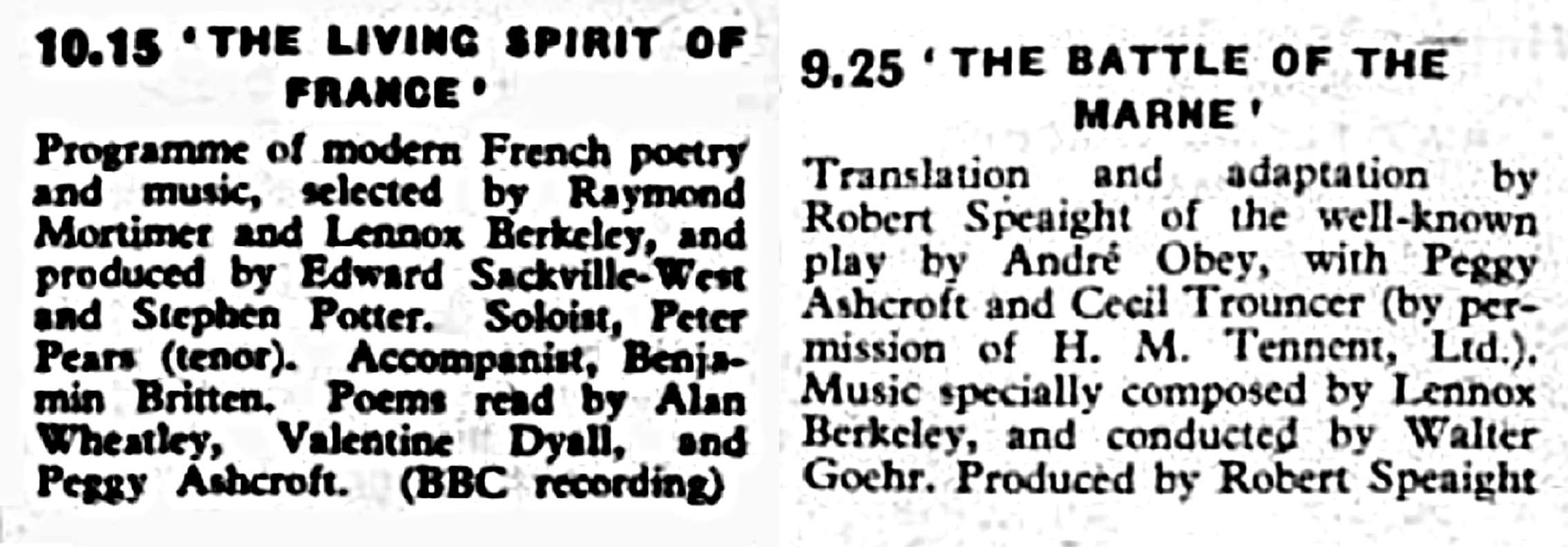

BBC music broadcasts, which could be received in Normandy, also contributed to Lemeland’s musical development. We can only guess at what he heard, but some of the BBC programmes available during the later war years would certainly have been devised by Lennox Berkeley, who had joined the BBC in November 1941, initially in the French Service and then in the Music Department. Berkeley was also associated with two literary broadcasts in August and September 1943 that were probably motivated – at least in part – by the plight of occupied France. Doubtless they would have been rather advanced for the ten-year old Lemeland if he had tuned in to them.

If the young Lemeland had tuned his wireless dial to the BBC’s French Service in 1942, he could have heard Berkeley speaking, in French, on ‘French Music in London’; and by early 1945, when listening to the BBC would have ceased to be politically risky, Lemeland could have heard Berkeley’s Divertimento, conducted by Adrian Boult, on a domestic BBC broadcast on 30 January.

The 1944 D-day landings in Normandy, and subsequent liberation of France, were formative for Lemeland and had two artistic consequences. First, he developed a lifelong interest in the cultures of the Allied countries. Second, the liberation inspired some of his most significant compositions. For example, the orchestral song cycle Songs for the Dead Soldier (1993) sets poetry by classic American poets and by Americans who participated in the liberation. A CD recording of it received the Grand Prix du Disque Charles Cros in 1995. (Berkeley himself marked the liberation with a piano piece, Paysage, ‘in honour of a redeemed France’, which Lemeland may have come across in later years.)

The immediate post-war years found Lemeland studying at the Lycée Claude Bernard in Paris, where he befriended Gilbert Amy, later to be a leading figure in French contemporary music. At that stage, Lemeland’s musical enthusiasms centred on Shostakovich, Prokofiev, Sibelius, Walton, Copland, American film music and jazz. Before long, the list expanded to include William Schuman, Walter Piston, Samuel Barber, Roy Harris, Elgar, Delius, Vaughan Williams, Britten, Tippett and Berkeley, among others.

Attracted by the richness of London’s musical life, Lemeland spent a year in London from (by my reckoning) the summer of 1953 to the summer of 1954, supporting himself as a sales assistant at Selfridges. This London residency undoubtedly contributed to his appreciation of British music and musicians. As a keen Prommer, he is very likely to have attended the premiere of Berkeley’s Flute Concerto (29 July 1953), and this event could have crystallized his interest in Berkeley. On the radio, while in London, Lemeland could have heard, among other Berkeley pieces, the Divertimento (6 July 1953) and the Concerto for Two Pianos (28 and 29 May 1954); and in the weekly Music Magazine he could have heard Berkeley talking about Britten (22 November 1953). Through the following decades Lemeland maintained his interest in the British scene, even developing an enthusiasm for his near contemporary David Bedford, who was a pupil of Berkeley at the Royal Academy of Music in the late 1950s. Lemeland particularly admired Bedford’s 1974 Proms commission, Twelve Hours of Sunset, which he considered a masterpiece.

Strikingly absent from Lemeland’s favoured composers listed above are French names. Although Lemeland revered earlier generations of French composers, particularly Roussel and Jean Rivier, he was unsympathetic to the turn French music took under the influence of Pierre Boulez in the 1950s, disliking not only the music but also an undercurrent of dogmatism that he associated with it. His own music remained, as he put it, ‘somewhere between impressionism and neo-classicism’. Eventual recognition came during the 1990s. In addition to the CD award mentioned above, he won a Diapason d’Or in 1997 for a CD of Airmen, which incorporates poems by British fighter pilots, and his opera Laure, ou la lettre au cachet rouge was presented in Switzerland during the 1994/5 season. His compositions were increasingly performed abroad, in Germany, Russia and the USA. The conductor José Serebrier, in particular, became a keen advocate of his music and recorded several of his symphonies.

Lemeland died in Paris on the night of 14/15 November 2010. His catalogue includes 14 symphonies, two operas, concertos, vocal pieces and chamber works. The chamber music often features unusual pairings, for example oboe and harp, clarinet and vibraphone, and French horn and guitar. The guitar forms a small but significant part of his output, and it was his guitar music that led to my meeting him in 1998. I had arranged to interview the guitarist Alain Prévost in Paris for the British magazine Classical Guitar. Lemeland had recently composed some pieces for Prévost, who suggested that the three of us should meet at a bistro one evening.

Lemeland arrived, tweed-jacketed despite the heat, and slightly distracted, but very friendly. His English pronunciation was quirky, though probably no more so than my French. When he enthused about ‘Laynoss Bairkhlie’, for whom he had once organised a concert at the British Embassy in Paris (see my account on pp. 29-32), it took me some time to work out whom he meant. Both he and Prévost admired Berkeley’s Sonatina for guitar, and the playing of Julian Bream. Lemeland said he was busy with his Symphony No. 10 and, pulling the manuscript score from a briefcase, put it before me. Flattered by his overestimation of my musical competence, I studied a few pages out of politeness. Following this meeting, we corresponded for a couple of years. Appearing in the Lennox Berkeley Society Journal would have delighted him.