Berkeley’s five film scores

Tony Scotland introduces Lennox Berkeley’s five film scores, including ‘The Sword of the Spirit’, ‘Hotel Reserve’ and ‘Out of Chaos’.

Lennox Berkeley enjoyed writing for film, and found the requirements of split-second timing an excellent discipline. In his middle years he wrote five film scores: three features and two documentaries. Prints of three are available at the British Film Institute, and fragments of some of the scores can be found at the British Library.

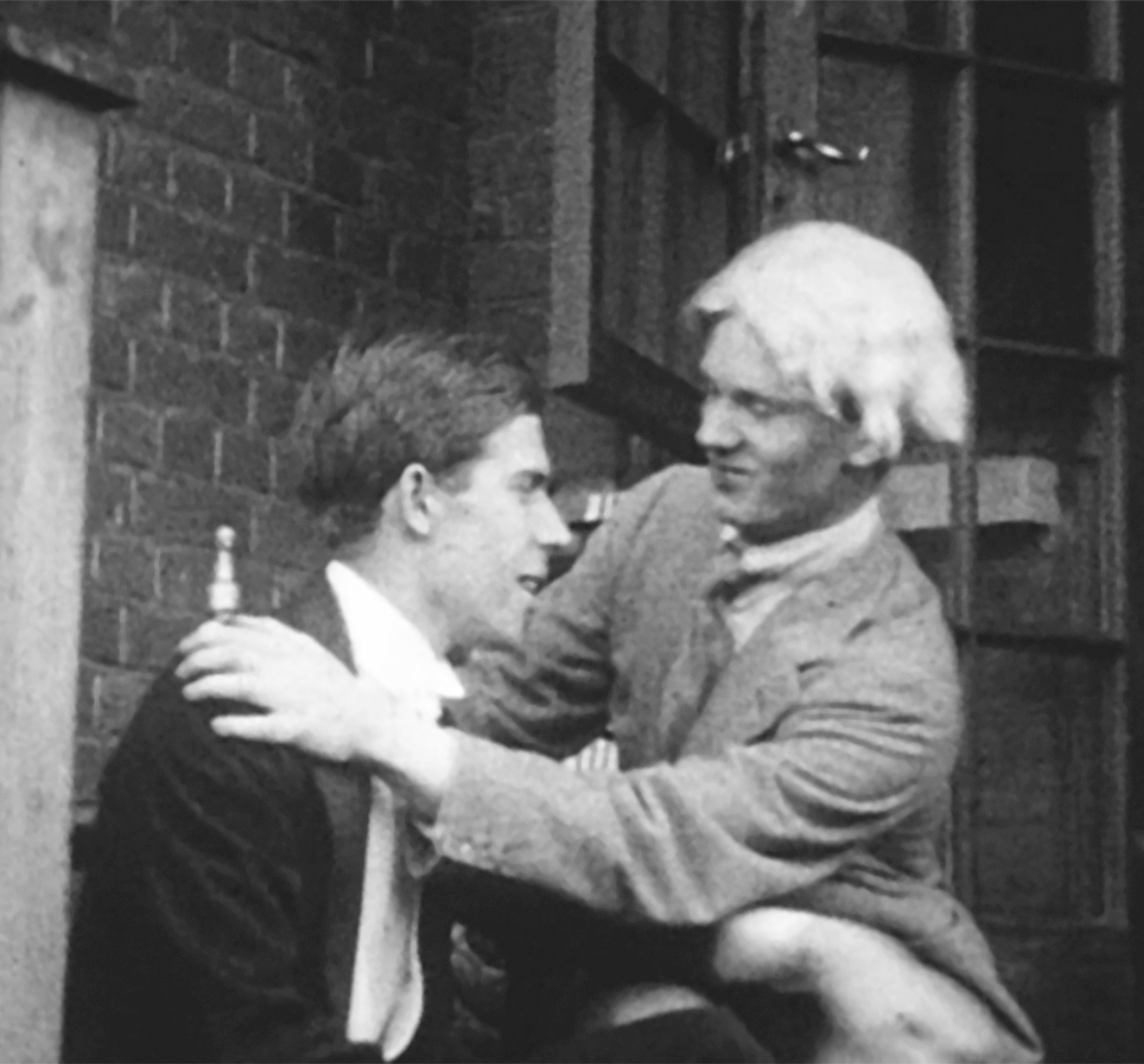

His first film was at Oxford in the twenties – an undergraduate romp called The Scarlet Woman – an Ecclesiastical Melodrama, written and directed by Evelyn Waugh with all his ‘Brideshead’ friends.1 The story revolves around a papal conspiracy to restore Catholicism to contemporary England; it is a sort of Gunpowder Plot with sex and booze, written in the satirical vein of Decline and Fall.

Lennox’s childhood friend John Greenidge played the Prince, who is converted first to Sodom and then to Rome. Waugh himself, in a wonky white wig, was the sinister and Catholic Dean of Balliol who carries out the corruption, John Sutro (who later became a film producer) played the crafty fixer Cardinal Montefiasco, while Waugh’s brother Alec was the Cardinal’s drunken mother who is having an affair with the Pope (played by a Catholic Guards officer under an assumed name). John Greenidge’s madcap brother Terence was the Irish Jesuit who steals the King’s signet ring to finance the plot, and the young Elsa Lanchester, then a dancer, was roped in (for free lunches) to play the drug-crazed Evangelical cabaret singer with whom the Prince falls in love. The plot is foiled when the singer’s Protestant scruples get the better of her, and she warns the King, who orders the death of Prince, Dean and Cardinal – by spiked cocktail.

Waugh conceived the project in July 1924. Filming started that same month, and a week or two later Waugh and Elsa Lanchester went round to John Greenidge’s flat in Great Ormond Street for a showing of the scenes shot so far. Waugh decided that he was already ‘quite disgusted with the badness of the film’ and regretted the fiver he had invested in it.2 There was a further, drunken screening of more of The Scarlet Woman at Oxford in November 1924; Waugh later remembered little of this occasion, except that he got a sword from somewhere, got into Balliol somehow and was got out again by being lowered from a window.3

It is hard to imagine that the usually sober Lennox was present that night too, though it is no less difficult to imagine how he could have conceived the music without seeing the film at least once before the first official showing the following year. Nothing whatever is known of his score, though he probably made notes about characters and situations and timings, then improvised on the night. A review in the undergraduate newspaper, The Isis, does not mention the music. Thirty-six years later Terence Greenidge recorded simply that ‘the film had a glorious First Night at the Oxford University Dramatic Society in 1925, Lennox Berkeley in charge of the musical accompaniment’.4

It took Lennox seventeen years to recover sufficiently to compose for the screen again, and then came three films in quick succession, during the war, when he was in a Reserved Occupation at the BBC, and serving voluntarily as an air-raid warden. The first was a propaganda documentary called The Sword of the Spirit,5 sponsored by the Ministry of Information to draw the Americans into the war by showing that British Catholics were already on-side, even if they did owe their spiritual allegiance to Rome. The title comes from the wartime movement founded by Cardinal Arthur Hinsley, Archbishop of Westminster, to provide ‘A Catholic’s Answer to Nazism’. The Sword of the Spirit crusade was intended for Catholics ‘and all men of goodwill’ who wanted ‘to join in the defence of the natural law and go forward to a just victory and a just peace …’.

The film shows Catholics attending Mass – in the old Latin rite – at Westminster Cathedral and in the shell of Southwark Cathedral, which had recently been bombed. ‘Our churches may be wrecked’, says the commentary, ‘but the spirit of Catholicism transcends material destruction.’ There are dramatic re-enactments of the bombing of the chapel of a famous Catholic girls’ school, when the Mother Superior plunges into the flames to rescue the tabernacle containing the blessed sacrament, and of a priest ARP warden climbing up into the ruins of a bombed house to give extreme unction to the dying victim of an air raid. There is also a roll call of Catholic war heroes, and footage of Catholic servicemen at Mass around the world – Polish airmen on land, British sailors at sea, Free French troops in the Western Desert. And in the middle of the film there is an address (with subtitles in Spanish – perhaps to reach the vast electorate of Hispanic Catholics in the United States) given by Cardinal Hinsley, who stresses the Church’s uncompromising opposition to totalitarianism and the necessity for spiritual rather than material goals, ‘if there is to be true freedom in victory’.

Lennox’s contribution is small but significant. He provides a short and dramatic prelude to accompany a shot of tanks rolling across a theatre of war, an urgent section for strings as the priest clambers through the ruins to the dying woman, and a rousing closing piece, which develops and harmonizes the theme of the hymn, ‘Hail Queen of Heaven, the Ocean Star!’, sung by sailors. Otherwise the sound effects are on-site recordings of Gregorian chant and polyphony (arranged by Henry Washington, later to become director of the Brompton Oratory Choir) and of the rumbles of bombers and anti-aircraft guns.

For Lennox this commission was particularly appropriate, since it gave him the threefold opportunity to play a part in propagating the prevailing spirit of patriotism, to honour his Church and to lay the ghosts of his harrowing experiences as an ARP warden in the Blitz.

His next film assignment was altogether different. Just before Christmas 1943 he was asked, at very short notice, to write the music for Hotel Reserve, based on Eric Ambler’s thriller Epitaph for a Spy. It’s about a shy Austrian medical student called Peter Vadassy, whose holiday snaps of lizards print up to reveal hidden guns protecting the naval port of Toulon. Accused of spying for the Nazis, Vadassy manages to persuade the police that he is innocent, but unless he can unmask the real villain among the other guests at the luxurious Hotel Reserve where he is staying on the Riviera, he could still be sentenced to death. Victor Hanbury directed the film for RKO Radio Pictures, James Mason starred as the hero Vadassy, and the screenplay was by Lennox’s friend, the critic John Davenport, who may have had a hand in choosing the composer.6

It was a tough assignment: the full score – all forty-seven minutes of it – had to be written in just three weeks. ‘I don’t think it is good to write as quickly regularly,’ Lennox told his old teacher Nadia Boulanger, ‘but it does no harm – except make one very tired – to have to do it occasionally.’ Lennox must have mentioned film music in previous letters, and Mademoiselle Boulanger had clearly expressed a certain disapproval, because, in this letter, dated 25 January 1944, he went on to say that it was not necessary for a composer to lower his standards when writing film music, but merely to use an easier idiom – ‘at least that is what I do.’ It was, he said, like the difference between poetry and everyday speech: so long as the difference was acknowledged, ‘we ourselves can keep the standard up.’ Lennox added that the requirements of film composition – writing music that had to be timed to the second, yet still satisfy the composer’s sense of form – provided excellent discipline.7

In the final year of the war Lennox found himself scoring another film – like The Sword of the Spirit, a documentary and a propaganda vehicle. Out of Chaos was conceived and made by Jill Craigie, a passionate young feminist film-maker, half Russian, half Scottish, who was to marry Michael Foot four years later. Ostensibly it’s about some of the official British War Artists – Anthony Gross, Stanley Spencer, Paul Nash, Graham Sutherland and Henry Moore – but actually it goes further than that: it’s a pioneering attempt to explain art to a largely philistine British public, a public that thinks it’s enough to know what it likes – and to show that art has the power to bring order, enlightenment and inspiration out of the chaos of war.

An opening scene shows London battening down the hatches as the skies darken at the start of the Blitz. Then the artists are introduced by Kenneth Clark, director of the National Gallery – looking extraordinarily ill-at-ease in a medium he was to master to perfection years later in the BBC television series Civilisation. Craigie tried to get him to relax and to chat to the camera, in a technique that was quite new then. But he can’t get his eyes off the script or even smile. Halfway through she persuades him to sit on the edge of his desk, but he’s even less happy there.

Next we see the artists at work in the field: Gross sketching Ack-Ack girls on an anti-aircaft gun battery; Nash studying the wreckage of German fighter planes and transforming the scene into his masterpiece Totes Meer (Dead Sea); the elfin figure of Spencer darting about in the Clyde shipyards fascinated by human forms, cranes and the ribs of ships; Sutherland seeing into the darkness of the Cornish mines; and Moore watching Londoners sleeping in the Underground during the air raids, and scribbling a note to himself to ‘Remember mouths open – try to get restless feeling’.

Then the finished works are shown to a group of sceptical visitors at the National Gallery, and the schoolmasterly art critic Eric Newton steps forward to deliver an awkward lecture on how to read a painting. These staged scenes in the Gallery now seem ridiculously artificial and dated, and Newton, who looks like the Grim Reaper, is almost comically condescending. But he makes a vital point, and it could equally well apply to any new work of art, at any time, perhaps particularly to music: beauty, he explains, isn’t about prettiness but comprehension. A painting isn’t a picture of a scene, but the artist’s vision of that scene; it’s as different from the scene that inspired it as poetry is from journalism. Only when we have discovered what the artist – or the composer – is saying can we begin to appreciate the artist’s work and to see it as beautiful.

Looking back later, Lennox made much the same point as Newton, when he told his beloved teacher Nadia Boulanger that setting a painting to music, for a film, was like turning a poem into a song: you have to understand it first. The method Lennox adopted in Out of Chaos, in order to key his music to the moving frames, was in three parts. First he wrote a musical impression of each painter’s chosen subject, then he elaborated on that impression as the artist set to work, and finally he produced what he called ‘a more orderly construction of impression and elaboration’ to accompany the presentation of the finished painting.8

His score starts with a trumpet fanfare, reaches a dramatic climax with the Battle of Britain sequence and footage of aerial combat, changing mood as the battle dissolves into Nash’s still and ghostly Dead Sea, and ends with a rousing theme that sounds like Elgar. Lennox planned to make an orchestral suite from the score. It’s not known whether this was ever actually performed in the concert hall, but three sections of the suite exist at the BL in a manuscript in his own hand.9

Out of Chaos is the first film ever made about modern British art; it gives a unique insight into the working methods of some of the twentieth century’s greatest artists. It also breaks new ground as a documentary film, introducing novel techniques such as the talking head. And it offers a glimpse of everyday life in London in wartime. So much has changed since the forties: not just clothes and hats, cars and advertisements, but modes of speech, courtesy, deference. And of course the film is of special interest to the Berkeley Society, because of its romantic score by Lennox Berkeley – played by the London Symphony Orchestra conducted by Muir Mathieson.

The film lasts half an hour. Jill Craigie wrote her own narration, and reads it herself. Her backers gave her a press showing which attracted a lot of attention, but the distributors refused to put it on general release, on the grounds that there was no market for such a film.

Lennox’s last film came three years after the war, when he was asked to write a score for an historical drama by Norman Ginsbury called The First Gentleman, which had been a West End hit with Robert Morley and Wendy Hiller. It’s set in the Regency of George Prince of Wales (played by Cecil Parker), and deals with his attempts to marry his beautiful but wayward daughter Charlotte (Joan Hopkins) into a rich and popular union. Instead she falls in love with a handsome fortune-hunter, Prince Leopold of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld (Jean-Pierre Aumont). Against the odds the marriage turns out to be a success, but then tragedy strikes and the princess dies in childbirth.

The music was ready by Christmas and recorded by the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra in London on 19 January 1948, with Sir Thomas Beecham conducting. After the session Lennox told his publisher that ‘everyone seems delighted with the music’, the great man had ‘behaved like a lamb’, and apart from one or two places where the timings had not been quite accurate, there had been no musical hitches. There were, however, some ‘technical mishaps’ (nothing to do with Lennox), including one in which the film stock caught fire – just as Princess Charlotte and Prince Leopold were enjoying their first passionate kiss.

The critics were not entirely enthusiastic. ‘Swamped in period costumes and decor,’ wrote one, ‘[it] is consistently good to look at, even when the plotline begins to drag’. Another described it as ‘a poorly mounted costume drama with a complicated script that moves at a snail’s pace’.

Lennox never turned to film again. Nor, for a while, did he need to. On the night before the grand opening of The First Gentleman Freda Berkeley gave birth to their first son, Michael Fitzhardinge, and composition took second place.