Tony Scotland on the faith in Lennox Berkeley’s music

In the Chapel of Lennox Berkeley’s alma mater, Merton College, Oxford, Tony Scotland talks about Berkeley’s faith and the way it is reflected in his music and that of his friends Ravel, Stravinsky and Poulenc.

Lennox Berkeley went up to Oxford in the year of the première of Walton’s Façade, when the gothic Edith Sitwell, in a towering turban with lumps of amber on her fingers, declaimed her nonsense poems through a megaphone. It was the decade of the shimmy and the Charleston, of flappers with Eton crops, and aesthetes in Oxford bags. The gilets jaunes of the Roaring Twenties were cocking a snook at their elders. They wanted change – but it wasn’t to come till after the next war. Merton in 1922 was still a male preserve, with a 10pm curfew, and compulsory Morning Prayers.

It was the morning service of the 10th of October 1922 that brought Berkeley into this beautiful chapel for the first time. Religion probably wasn’t uppermost in his mind then, nor were the academic subjects he’d just signed up for. Instead his head was full of music – Bach and Mozart; his own, untutored, early compositions; and the revolutionary new sounds bursting out of Paris through the gramophone horn – the percussive scores of Stravinsky and shimmering Ravel. Little did he imagine then that he’d soon be rubbing shoulders with both these giants of new music.

It came about when Ravel visited London in 1925 for a schedule packed with concerts, meetings and dinners. But Ravel was hopelessly disorganised: he had no idea of time, picked at his food, liked holding forth, wouldn’t go to bed, and couldn’t get up when he did. Furthermore his English ran to just three words – ‘one’, ‘two’ and ‘pencil’. So his hostess – a family friend - asked young Berkeley to look after him, to get him to the church on time. Berkeley wasn’t actually much better organised, but he spoke perfect French, he was passionate about music, charming and a good listener.

The chemistry worked – and one day Berkeley plucked up the courage to show the great man a harpsichord March he’d written here at Merton. Ravel smiled at harmonies not a million miles from his, but frowned at the lack of technique. What Berkeley needed, he said, was a strong dose of Nadia Boulanger – the greatest composition teacher of the age. And he promised to open the necessary doors.

Come 1926, when Berkeley graduated, he didn’t have to worry about his inglorious Fourth: instead he sailed away to Paris to start six years of intensive study under the stern but loving teacher who was to become the most significant influence of his life. Through Nadia Boulanger, Berkeley learned everything – not just about music, but about Life – and met everyone: Stravinsky; the great patron, Winnaretta, Princesse de Polignac; Poulenc, Milhaud, Honegger.

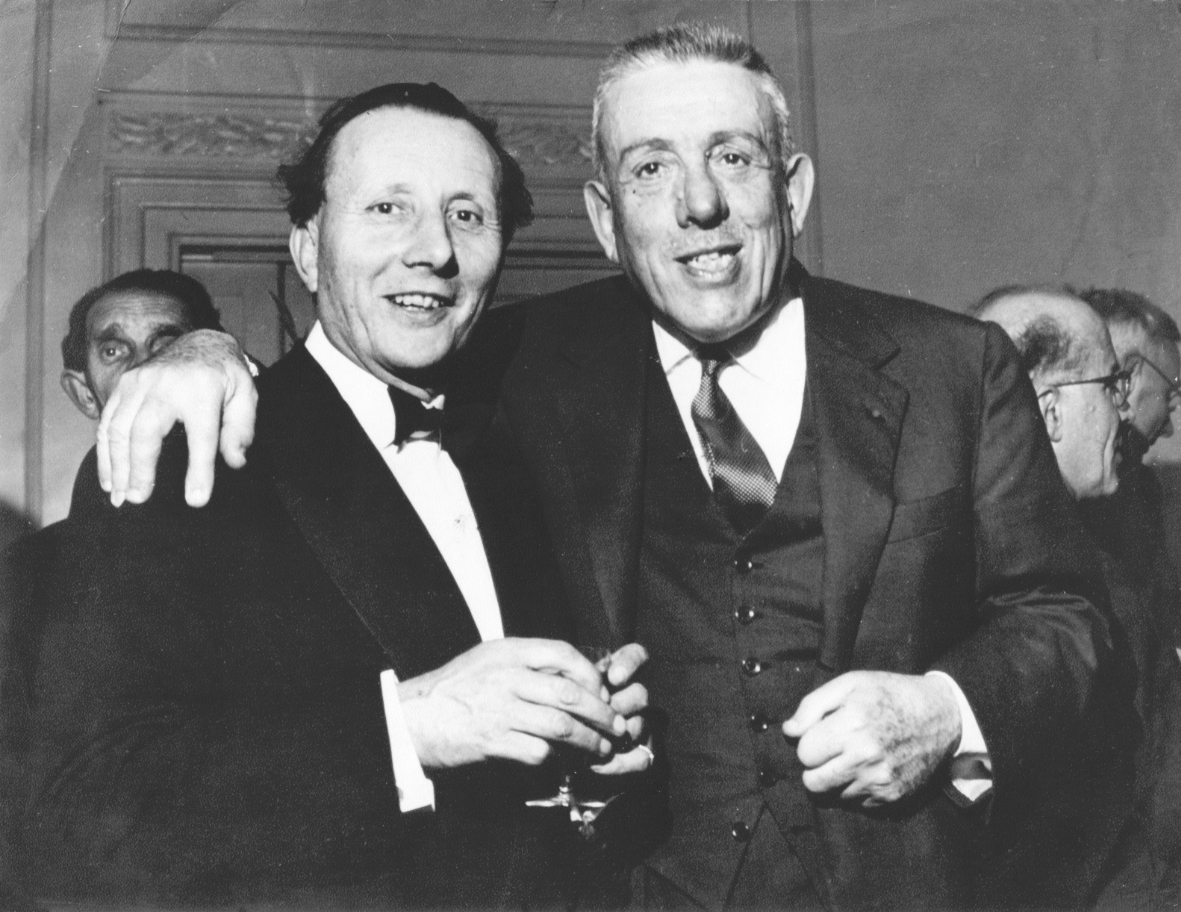

To the charming and playful Poulenc Berkeley easily drew close, and the two remained friends till Poulenc’s death. But Stravinsky was a generation older, an international celebrity, and not a little awe-inspiring. Stravinsky’s son, Soulima, a pianist and fellow student at the Boulanger school, broke the ice by inviting Berkeley home to supper occasionally. The family had a large flat near the President’s palace, full of practical old furniture, modern paintings, a barrel of fine claret – and a dense cloud of Stravinsky’s non-stop Gauloises. These two different men – one at the top of the tree, the other at the bottom – had much in common: noble blood, complicated love lives and an adoration of their mothers – and of Nadia Boulanger. They were both musicians’ musicians, constantly exploring new ideas, and both, like Poulenc, composed at the piano. More significantly both were profoundly religious in a quiet, private way.

Stravinsky and Berkeley, Poulenc too, were strongly influenced by the Catholic evangelical revival in France between the wars. Poulenc made a pilgrimage to the shrine of the Black Virgin at Rocamadour – and had a conversion experience which restored him to the faith of his youth, and led to his Litanies à la Vierge noire and the later sacred works. Stravinsky, who had grown away from the Russian Orthodox Church, was so impressed by the rich tradition of Catholic thought that he considered converting to Rome, but instead turned back to his Orthodox faith with a new devotion. One of his first compositions after this re-awakening was a setting, in Old Slavonic, of the Pater Noster, inspired by his memory of the church music of his childhood in Russia and Ukraine. He later made the version in Latin which we heard here today before the Berkeley anthem. It was from this time, the mid-twenties, that Stravinsky made a habit of praying every day, before and after composing. He also surrounded himself with the ambience of old Russia: candles, incense, icons, bells and crosses and at one point, he even invited an Orthodox priest to move in with his family.

Berkeley had been wrestling with the challenges of religious faith since his last year or two at Oxford. His father was a Protestant rationalist, his mother a believing High Anglican. Falling in with the Anglo-Catholicism of some of his Eton friends at Christ Church, who were beginning to look to Rome for authority and guidance, Berkeley discovered Thomas à Kempis and The Imitation of Christ, which introduced him to the mysticism that lies at the heart of Catholicism. Though he had no problem with faith itself, he had every problem identifying where the true Church lay. Inspired by the example of Boulanger’s Catholic piety, discovering through her the sacred music of the baroque, and finding for himself the old Latin liturgy and Gregorian Chant in the dark and mysterious interior of the basilica of Sacré Coeur near his flat, he was ripening for conversion. And on 16 October 1929, taking the baptismal name of François, he was received into the Church, gladly accepting the immutability of its doctrines and the discipline of its rules.

His new Catholic faith brought him immense happiness, though he was all too aware of how short he fell of its lofty expectations. So it was some years before he felt confident enough to compose for his new Church, but when he did – after the war, after his marriage – his Masses, motets, canticle settings, and other sacred music became – and remain – a staple of Christian worship in cathedrals, churches and university chapels.

Like Stravinsky, Berkeley believed that music comes from a profound and mysterious source, and that its purpose was to lift the human spirit and to praise God.