Lennox Berkeley unfinished opera 'Faldon Park'

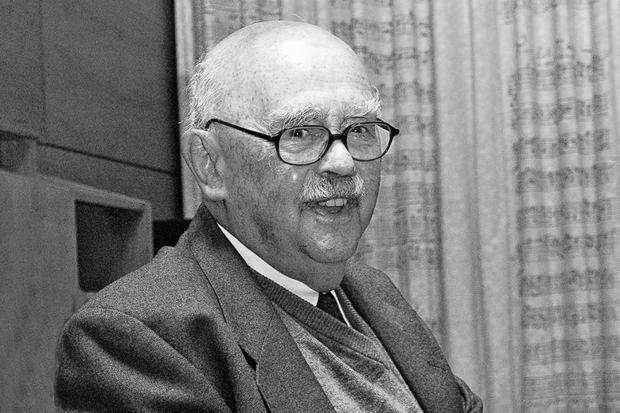

Handel scholar Winton Dean, librettist of Lennox Berkeley's opera 'Faldon Park', tells the story of why it was never finished.

I first met Lennox Berkeley with Benjamin Britten at Cambridge in November 1938, on the occasion of the première of the Auden-Isherwood play On the Frontier (with music by Britten), when we had an animated conversation on modern music and I expressed heretical opinions about Stravinsky. I was struck at once by his personal charm, modesty and air of sweet reason, though I had not much liked the only music of his I had heard, the Psalm Domini est terra at the 1938 Three Choirs Festival in Worcester Cathedral. The works he composed during the war, in which his distinctive lyrical gift began to ripen, gave me much more pleasure; I admired the String Trio1 and Divertimento2 and in May 1947 greatly enjoyed the Symphony No 1.3 On the spur of the moment I wrote to tell him so, reminded him of our Cambridge meeting, and asked if I could go and see him. He gave me a warm welcome at his flat in Warwick Square;4 this was the start of a close friendship that lasted until his death.

My chief memory of this occasion is the appearance of Freda while we were talking. Lennox did not introduce her, and I was not clear whether she was his wife or his mistress. They had in fact recently married.5 The following spring they paid their first visit to our house in Milford,6 and I took a photograph of them in the garden, with Freda palpably pregnant. This was perhaps the first visual record of Michael’s existence.7 After that Lennox and Freda spent week- ends with us almost every year, first at Milford, then at Hambledon8, with one, two or three sons, who left remarkable signatures in our visitors’ book.

Lennox was then hard at work on his opera Nelson.9 I was already fascinated by opera, and was thrilled to find a modern composer whose views coincided very much with my own. His acclaimed model was Verdi, especially Otello; his methods were traditional in that he made regular but flexible use of arias and ensembles; and he wrote memorable and even haunting tunes. The voices carried the drama and were not mere filling or, as in many modern operas, a prickly thicket of angular intervals. On each visit he played what he had written, sometimes with Philip Radcliffe10 sight-reading when the music exceeded the reach of two hands, and all three of us endeavouring to sing the voice parts. In this way I became familiar with the music long before the performance; a little of it was composed at our house. Lennox’s voice was so deep that he seemed to sing almost everything an octave or even two octaves below pitch; we felt it was quite an achievement when he rose to the bass stave.

We had endless discussions about the problems of operatic form and particularly about dramatic timing. I lent him my score of Un ballo in maschera when he was debating whether to use a backstage band for the dance music in Act I, and if so how to combine it with the pit orchestra. A little later he borrowed Simon Boccanegra, and discovered after some months that he had forgotten to return it. I felt that Alan Pryce-Jones’s libretto, though admirable in many ways, sometimes failed to make the most of the dramatic possibilities and hung fire when it should be moving on. Encouraged by Lennox, I made a number of suggestions for improvement. There seemed a danger that Nelson might appear too much the conventional tenor lover at the mercy of his emotions rather than the man of action, and that the call of duty might not be sufficiently emphasised. I suggested the conflict would be sharpened if Nelson’s former commanding officer, Lord St Vincent, until recently First Lord of the Admiralty, appeared in the middle act and put the case for the country’s need, perhaps reproaching Nelson for personal weakness. Lennox liked the idea, which he called ‘a most ingenious solution so long as we are sure it’s necessary’, but was afraid of the act becoming too long. He and Alan Pryce- Jones discussed the idea and were ‘enormously impressed by [its] ingenuity and suitability’, but Lennox pointed out that ‘the opera is not really about Nelson’s career, but about his relationship with Emma, the former only being shown in so far as it has bearing on the latter’. And he apologised, quite unnecessarily, for letting me take so much trouble (April 1950). Two years later he reverted to my suggestion, proposing to use it in a new scene at Merton (Act II Scene 2), with a love duet and Nelson’s call to Trafalgar as the first scene in Act III. He sent me a new scenic layout to this effect. (At this stage he may still have been uncertain about the final scene for Emma after Nelson’s death.) The outcome of all this was the introduction of an Admiralty representative, Lord Minto, in the second scene of Act II.

In 1953, after the public run-through 11 of part of the opera with piano accompaniment at the Wigmore Hall on 14 February, I sent Lennox a scheme for tightening up the Portsmouth scene (II i), which I felt after a splendid opening petered out and became episodic, especially with the appearance of Emma and her mother in disguise. He thought this ‘really brilliant’: if he decided to make any change at all, it would certainly be on the lines I suggested. Unfortunately I cannot remember what my solution was (though Lennox intended to incorporate it in a proposed revision after performance); since he habitually lost or mislaid letters, I doubt if it has survived.

The year 1954 saw the production of two Berkeley operas, A Dinner Engagement at Aldeburgh in June and Nelson at Sadler’s Wells on 22 September. (There had been some question of Nelson having its première at the Holland Festival, also in June.) I wrote a preliminary article in The Listener of 16 September, emphasising the difficulty of the subject: success must depend in the last resort on the character of Nelson himself.

If he is not presented as a man of magnetic personality, a hero and a genius, the opera is done for. An English audience will judge him by different standards from those it applies to the average operatic tenor. It is never easy to portray genius on stage, and the sphere in which Nelson’s genius shone hardly lends itself to operatic treatment.

Lennox was pleased with the Sadler’s Wells performance, which I thought failed to do the opera justice, and modestly accepted the rather cool reaction of the critics. Ernest Newman was curtly dismissive, and Desmond Shawe-Taylor considered much of the opera ineffective through lack of dramatic experience and Nelson himself sadly undervitalised. Almost everyone was agreed that too many words were lost. As a result of the critical reception a number of cuts were made in later performances, chiefly in the first act. The omission of the first of Mrs Cadogan’s two bird songs was a distinct improvement, but that of Nelson’s ‘Down the river reaches’ seemed to me a calamity; apart from the musical loss, it brought in Madame Serafin the moment Mrs Cadogan goes to find her, and made the fortune-teller’s scene seem longer rather than shorter by throwing out the scale.

My review in The Spectator was not uncritical, but it pleased Lennox:

I think it is extremely fair and I agree with almost everything you say. I am only too conscious of the things that the opera fails to do, but I can’t quite make up my mind how far they are due to lack of experience on my part or to my not having the kind of operatic gift that would enable me to tackle that particular subject with complete success. On the other hand, I do feel that the good things really did come off.

In the same letter (8 October) he said he had been completely carried away by The Turn of the Screw, ‘which I think the most beautiful thing that Ben has yet written’. Four days later, after I had written enlarging on the review, he added:

I agree with most of the reservations you have about Nelson – I think that the mistakes we made are mainly ones of timing, also I don’t think I gave N. music that was quite forceful enough … The Dinner Engagement has really been more successful than Nelson, but of course I was not attempting so much.

Nelson was not the only subject we discussed. Lennox gave me helpful practical advice when I was arranging a suite from Bizet’s fragmentary opera La Coupe du Roi de Thulé and filling gaps in the music. I convinced him of the advantage of using opus numbers, which made it easier to grasp the chronology of his works, and drew up a provisional catalogue, assigning numbers as they seemed appropriate. This was modified by Lennox and continued later with the co-operation of Peter Dickinson, and eventually reached three figures with Faldon Park. I remember the amusement with which Lennox pointed out that his Opus 1 was the Violin Sonata no. 2, and his subsequent concern over the placing of certain works whose existence he had totally forgotten, including the Five Housman Songs and the Cello Concerto.

Our many interesting discussions over a period of more than four years, and my growing sympathy with Lennox’s music, led me to suggest collaboration on a future opera. I was convinced that he had the skill and imagination to compose a very moving opera, perhaps a masterpiece, provided he found a suitable libretto. For all my admiration for the music of Nelson, I felt that the story of a great national hero and a man of action was not the perfect vehicle for him; and A Dinner Engagement, though perfectly turned and excellent of its kind, expressed only one aspect of his gifts. What was required, it seemed to me, was a comedy with a strong lyrical or romantic content. An idea was beginning to form at the back of my mind, and the excitement attending the production of Nelson gave it a push. I at once dropped a hint to Lennox. His reply, in the letter of 12 October already quoted, was enthusiastic:

I’m longing to know what your idea is, it sounds the right sort of thing for me – lyrical with opportunities for humour (and a nice cosy ghost who is not frightening!)

I then set down to draft a scenario; but the subject ran away with me, and to my astonishment the complete libretto came out in less than three weeks. It passed through several versions later, modified in detail as a result of requests from Lennox and further thoughts of my own, but these were all verbal changes or matters of adjustment: the outline of the plot, the characters and the central ideas remained the same. I wrote it in set numbers, with arias and ensembles in verse, linked by prose dialogue (to be sung, not spoken, except for one key line); the verse metres were fairly regular and mostly rhymed. In all this I was following Lennox’s expressed preferences.

I wrote the following synopsis for the Arts Council many years later, but it could as well date from 1954.

Faldon Park

There are two acts, each with two scenes linked by a transformation during which the music is continuous and the main curtain is not lowered.

Act I

The present day. The terrace of Faldon Park, an old country house in the Midlands, which is being sold up: the Skipton family, who have lived there for centuries, can no longer afford to maintain it. The house and park are to be taken over by the Council for public recreation, the contents sold to pay the family’s debts. The removal men are carrying out furniture and pictures. Barbara, daughter of Sir Digby Skipton, seventeenth baronet, passionately resents the loss of her home, preferring to turn her back on the present and live in the past. Sir Digby warns her that this is impossible. She asks for five minutes to say goodbye to the Park. He agrees and goes to wait in the car.

Scenic transformation to a different view of the terrace and Park. The date is November 1745. Estate workers and neighbours are in a state of panic: the army of the Young Pretender is approaching, reported to be sacking cities and hanging innocent citizens. Sir Bartholomew Skipton, eight baronet, and his wife have personal troubles as well. Their only son and heir, Martin, is estranged and rebellious. He refuses to marry Eleanor, daughter of their neighbour Charles Fothergill, as they wish; instead he dissipates his substance in London on drink, women and Italian opera. Sir Bartholomew is determined to disinherit him despite his wife’s protests. Their quarrel is interrupted by the entrance of Martin, a cynical young man who taunts his parents with setting a poor example of the married state into which they propose to ensnare him. He rejects leading strings and a dull life in the country, and when he learns of the Pretender’s approach he expresses delight: it may let a breath of fresh air into their stuffy conventional environment. His parents are outraged; Fothergill, an elderly antiquarian who dabbles in archaeology, is shocked by Martin’s lack of respect for tradition; Eleanor – young, inexperienced, a little priggish and in love with Martin – tries to defend him, suggesting that if they treat him gently he will come to heel. This hurts Martin’s pride and makes him angrier than ever.

All are at cross purposes when Colonel Augustus Skipton, Sir Bartholomew’s brother, enters at the head of the local militia. An unimaginative retired soldier, confident of his ability to deal with any practical problem, he rebukes them for pettiness when the country is in mortal peril. He sings a song about the Battle of Blenheim, the supreme experience of his youth, when “the genius of our land was free and strong”. His evocation of the spirit of that glorious victory rouses everyone to a state of patriotic fervour.

Suddenly Barbara appears, dressed as in Scene I. The others are first puzzled, then afraid – all except Martin, who gazes at her as if transfixed. Some of them take her for the Pretender, others for a ghost. The Colonel, at a loss before anything he cannot at once understand, orders the militia to retreat and reform behind the orangery. Fothergill alone is interested, but the others drag him away; they must not run any unnecessary risks.

Martin and Barbara are left alone. Each recognises in the other something glimpsed in dreams, something essential to the completion of their personalities from which they have unconsciously drawn back. The act ends with a duet in which they acclaim this discovery across the centuries. Two or three estate workers peer round the balustrade of the terrace, look at each other in amazement, tap their foreheads and cross themselves.

Act II

The great hall of Faldon Park a few days later, early December 1745. Sir Bartholomew, Fothergill and the Colonel are anxious, restless and baffled. Not only is the country rent by civil war, but the natural order seems to have been subverted. Martin is in love with a ghost and wanders in the Park night and day, scarcely stopping to eat or sleep. Fothergill has consulted every available authority, including the Demonologie of King James I, and can find no precedent. Sir Bartholomew has sent for the Bishop. The Colonel will fight the Scots, alone if necessary, and has placed house and grounds in a state of siege, but he fears the supernatural and therefore despises it. Fothergill remonstrates with him: in the course of his excavations in the Park he has sometimes fancied he heard stirrings from other ages, and he cannot dismiss the idea that time may have more than one dimension and reality consist of something more than what we see and touch and hear. Astonished, the others ask if he would let his daughter marry a man infected by sorcery; Fothergill admits that his imagination may have carried him away. Lady Skipton and Eleanor find their men-folk in sad confusion. Sir Bartholomew would now prefer Martin to spend his time in London on wine, women and opera rather than consort with a phantom. The assumption that as a consequence Eleanor will reject him elicits from her a resolute declaration of her love, in this world or the next. The men propose to cure him of his madness by making him join the army.

The light begins to fade, and a chill of fear grips the company one by one (quintet). Barbara enters from the Park as the rising moon shines through the windows. They shrink back, denouncing her as a witch and the cause of their troubles, though she assures them she is of their kin and the Park is her home. They are convinced that their civilisation is about to collapse and all are doomed. She sees that they are frightened not of her or the Pretender but of the future, of life itself, and tells them their fears are groundless. Their chains are of their own forging; the prospect they find so dark is bright as the moonlight now flooding the Park. They are baffled that she should seem to know the future – a ghost with the gift of tongues. Barbara proclaims ecstatically that future and past are one and all opposite things part of the same experience – comedy and tragedy, youth and age, life and death.

This is too metaphysical for the Colonel, who itches to get back to his troops. The others suspect that Martin may be in danger, but Eleanor is convinced that they must trust Barbara. When Fothergill objects that they do not know who she is, Eleanor replies that she is hope, the light he is seeking in dark places; they must put fear behind them. Martin comes in from the Park and hails Barbara as the goddess of the moon who has reconciled all his rough places. First Eleanor, then the others begin to feel a resurgence of hope and to accept their own inadequacies. Eleanor recognises the unselfish nature of love, and the Colonel his recognition of the intangible element in life, Fothergill his retirement from the present into the past, Lady Skipton her possessive attitude to Martin, Sir Bartholomew his fear of old age and death. Barbara wishes to share the wealth and wisdom of the Park with everyone everywhere.

Suddenly the estate workers, militia, etc. burst in, wildly excited: the Pretender has fled, the country is saved. They prepare to celebrate with bonfires and fireworks. The Colonel recalls the aftermath of Blenheim, the defeated French in flight across their frontier. All depart in jubilation except Martin and Barbara.

Martin pours out his gratitude to Barbara for opening his eyes to the beauty of the Park and the richness of life and for revealing the shallow selfishness of his ways. He regrets only that he can give her so little in return. She replies that, on the contrary, he has done the same for her – and more: he has taught her the difference between love and possession. The Park is not her private domain but a treasure for all. Martin feels a pang that in gaining one priceless gift he has lost another: can they not prolong their moment of happiness? She answers that they have stolen it out of time; they must not spend its radiance on themselves. ‘Not by our captures but by our surrenders / In love and life we set the spirit free’. Each will live for the rest of his days with the vision snatched from time ever before his eyes.

As the moon sinks Martin turns to the shadows at the back of the hall, where he meets his parents, Fothergill and Eleanor. He bows to them, and Fothergill places Eleanor’s hand in his. The scene changes back to the present day. Barbara is standing before a large picture of an eighteenth-century family group. Sir Digby comes in, observing: ‘That was a long five minutes’. ‘It was an eternity’, she replies, and asks if they cannot keep just this one picture. He reads the label: ‘Sir Martin Skipton, ninth baronet, of Faldon Park, his wife Eleanor and his children. By Sir Thomas Gainsborough, 1765’. He says it is the most precious thing they have and will pay almost half their debts, but seeing her deeply moved he offers it to her. She looks searchingly at it, and refuses: she does not need what is already in her heart. She has dreamed a dream that will sustain her always, and will share it with any spirit lost in time who fears the future as she has done. ‘With all the common wisdom wrung from time / Shall we who follow be less bold?’

The removal men come in and take away the picture. Sir Digby, seeing Barbara wrapped in thought, follows them. Her mind running back in time (to the earliest point touched by the story) and reflecting on its mysterious unity and its power of healing, she sings the final lines:

On Blenheim field the sun went down, But in the night an angel passed that way And where the wrecks of men and guns were strown Young corn and flowers rose to greet the day.

She goes slowly out. The curtain falls on an empty stage.

* * *

I felt guilty and rather ashamed for presenting Lennox with a fully-fashioned object instead of a rough sketch; that was not at all my idea of how a librettist ought to collaborate with a composer. The whole thing had been thrown up with great force by my subconscious mind, where it had clearly been building up unseen and unsuspected; it had virtually written itself. For a long time I was unable to account for this, or to discover the source of the central idea: the girl and the young man separated in time and beyond each other’s reach, yet united by a spiritual link that not only conquers time but solves the apparently intractable problems that corrode their happiness and inhibit the development of both their characters. Eventually it dawned on me that it was an idealised transference of the strange and wonderful relationship that obtained between Brigid12 and me nearly twenty years earlier. There were also a number of subsidiary ideas, mostly concerned with the operation of time, that had worked themselves out quite convincingly without any conscious effort on my part.

For a long period I had been consciously suppressing a strong creative urge in favour of a career devoted to musical scholarship, a decision of which I was half-ashamed and which I suspected was the product of fear or cowardice. As soon as I began to think about Faldon Park, the urge took its revenge. It followed that the libretto meant a great deal to me, and the circumstances that finally prevented its fruition were a cause of acute disappointment. I still believe that the central idea is valuable as well as original, though I am less sure of some of the language; indeed I feel that it had greater potential than anything else I have written. But a libretto has only a half-life; until it has been irradiated and transcended by music it is a dumb and wingless thing that might as well never have been born.

Lennox’s reaction on reading it was a mixture of fascination and alarm. He was greatly attracted by the subject, yet shrank from the necessary labour and what he saw as certain difficulties in the treatment, in particular the numerous ensembles (‘I am not Mozart’). I made various amendments at his suggestion, including an aria for Barbara shortly before the final curtain, and he considered this a great improvement (July 1955). He felt he needed at least eighteen months free, but with his growing public success and reputation commissions were coming in thick and fast, and he did not like to refuse them. Many were for major works. A request from the English Opera Group for a piece with Eric Crozier 13 resulted in Ruth, a lovely work, but more like a cantata than an opera. (Lennox wrote to me in October 1956 that he thought the third scene too long and ‘the ending rather ineffective but otherwise I was pleased and feel that I have made a certain amount of progress, operatically as well as purely musically’.) Then there was the Symphony No 2 for the City of Birmingham Orchestra, which made slow progress; and later another one-act piece (Castaway) with Paul Dehn,14 to make a double bill with A Dinner Engagement. This was commissioned by the librettist. There were countless other projects, which pulled him in many directions; it was not in his nature to say no. His publishers, who probably felt that a full-length opera would monopolise his energies over a long period, were constantly pressing him for orchestral works. I endeavoured to possess my soul in patience; rightly or wrongly I did not feel entitled to apply pressure.

Again and again over many years he returned to Faldon Park and announced his intention of reconsidering it. In April 1971 I made a slightly revised version, which he proposed to study on his annual visit to Monaco. ‘I have great hopes about it – the fact that it is basically, as you say, a comic opera but having lyrical possibilities is exactly what would suit me.’ Two years later he was about to have another look at it, when three commissions one after another, which he could not bring himself to refuse, deflected him into other fields. My congratulations on his knighthood (June 1974) made him search for the libretto, which he could not find ‘owing to the usual chaos’. So I sent him a fresh copy, which he took to France on holiday, at the same time making some more explicit comments:

Already I think that there are some lovely things in it, but also a good deal that I don’t think I could set as it stands; it’s musically very ambitious – I love ensembles, but they’re very difficult to write – and there are so many here that I fear I should not survive to see it on the stage!

And in a postscript: ‘You must remember that I’m 71 & my name is not Giuseppe Verdi’. Accordingly I undertook another revision and simplified or removed a number of ensembles. Still nothing happened – until April 1976, when Thalia15 and I took a step which we should have taken earlier had we thought of it. This is one of only two letters to Lennox of which I kept a draft or copy (for the other, see below). Since it may have a modicum of historic interest, I quote it in full.

First of all, very many thanks to you both for the delicious dinner and happy conversation last evening. We got home very quickly in under an hour, though I did not get to sleep till 4a.m. through thinking excitedly about the libretto. Now today an idea has struck me with considerable force – the result (of all things!) of a communication from our tax accountant. A sudden rise in dividends combined with the vicious behaviour of Mr Healey 16 is about to push us into a bracket where we pay tax at a rate of 98% on the top part of our income. There is no point in this: the capital is serving no purpose. Then suddenly I thought of a way to put it to a far better use. Why not let us commission the opera? I seem to remember you telling me that something similar occurred with one of the Paul Dehn librettos. I have no idea what the proper fee would be, but we could easily raise two or three thousand and probably a great deal more, with no delay and without any appreciable drop in income. It would give me enormous satisfaction, and we would both feel we were doing something really useful, practically and artistically, and benefiting lots of others (including posterity) as well, since I am now absolutely confident (a) that the libretto is good and (b) that you really like it.

Much will depend, of course, on how you get on with your preliminary trial. But if you approve of the scheme I would respectfully submit (though not of course insist) that it might take priority over other commissions. This is not only for selfish reasons: I have always felt that (in big works especially) you are best with words, and that you have a gift for the theatre that has been undernourished. Nor am I alone in this. What do you think? The whole thing could be a secret between us. Thalia very much agrees with all this.

Don’t ask for anything less than you think you ought to receive for a full- length opera!

Lennox replied (25 April) that he was ‘quite overwhelmed by your generous offer’, and he would certainly give it priority if he accepted the commission. A complication was that Chesters wanted him to do another orchestral work and mentioned a possible commission from the RPO. After finishing a rewrite of the troublesome Second Symphony and composing an organ work, he intended to sketch part of a scene from the opera, adding, ‘I quite agree that if I’m to do it at all, I must start reasonably soon; I shall be 73 next month, and time is getting short – it must be now or never!’ He also pointed out that he would need ‘reasonable assurance that it will be put on’, and mentioned that George Harewood, 17 a friend of both of us, might consider it seriously.

I had already shown the libretto to George and Edmund Tracey 18 the previous summer. Both were very enthusiastic. George ‘vastly admired’ the skill in shaping the various numbers, and said he could imagine Lennox ‘reacting to the romantic involvement of Barbara and Martin very well indeed and finding it as touching as I did’. He had two reservations: the passages dealing with ‘information’ were rather long and might have to be reduced (this was easily managed), and ‘the element of nostalgia contained in the whole conception’ might not appeal to composers or, more particularly, critics nowadays. ‘We tend to be so fiercely contemporary that anything which is neither dealing with fundamental issues nor relevant to everyday and preferably lower-class life is out.’ My answer to this was that the break-up of old estates is a contemporary issue and Barbara’s experiences during the course of the opera force her to accept the terms of modern life from which she ran away at the start.

On 5 September 1976 Lennox wrote that he was trying to make a rough sketch of part of the first scene.

I’ve been thinking of your libretto a lot and find that in many ways it suits me in particular very well, but it’s very demanding – for example, hardly have things got going before the composer is expected to write an ensemble that will combine four different arias – or at least ariosos – an excellent idea, but damnably difficult to carry out. At the same time, there are many things I like very much – the ending, for instance, is very touching and could be beautiful.

In the event he set the four-part ensemble superbly, though he said it nearly killed him. In the same letter he told me he had accepted a commission to write his Symphony No 4 for the RPO for 1978, and wanted after that to write something - ‘a fairly short sort of Cantata’ – for the Three Choirs Festival, which had promised to make a special feature of his music at the 1978 Festival. He added, not for the last time: ‘I only wish I were ten years younger!’

Five days later (10 September) Edmund Tracey wrote to me:

If Lennox still feels he wants to embark on writing a full-length opera, and if you both feel that it is of a scale and nature suited to this house we would be delighted to put it on when it is ready.

He added on 16 November that he was trying to interest the Arts Council ‘in some sort of commissioning fee for the Berkeley/Dean opera’, and asked me for a short synopsis of the plot. Three days later Lennox informed me of a letter from George confirming that the Coliseum would put on the opera – ‘all very encouraging, and I long to be able to get down to it’. He was pleased to hear of the approach to the Arts Council, and proposed to work at the opera and the symphony alternately, turning to the former when he got stuck in the latter.

I think this might be a reasonable plan as I so often get stuck that it could be a god idea to have something else to turn to … I know that you have waited patiently over all these years, and I’m deeply touched by your confidence that I could ‘do the job’; I wish that I could devote myself to the opera right away, but I found it difficult to refuse the R. P. O. offer – it’s rare for one of our London orchestras to commission a contemporary composer. I only wish I had more facility and could go a bit faster, there would then be no problem.

He would let me know when he could accept a commission for the opera (12 December 1976).

The following year was a hectic one for him; he had reached ‘a rather traumatic moment with the Symphony’ and did not feel he could talk seriously about Faldon Park (25 July). Nor was 1978 any less fraught: he had intended to start the opera early in the year, but spent three months rewriting part of the symphony 19 and felt he had to accept two other things in connection with his 75th birthday year, a motet for the Three Choirs and a work for flute and piano for James Galway to play at the Edinburgh Festival. He would have a go at one section of the opera and a further look at the libretto with me ‘before committing myself to such an enormous task – at my age, when I can clearly only have a few years left, I must be certain of what I can do and what I can’t’ (9 April).

There was a party at the Festival Hall and various concerts in honour of his 75th birthday. At one of them I heard his Stabat Mater, which I had long considered one of his finest works, and was startled by the coda of one of the movements, which exactly reproduced, in harmony, spacing, key and instrumental texture, the music I had imagined for the closing bars of Faldon Park. Inevitably various scenes of the libretto had put music into my head, though I never supposed that this would have any significance for Lennox. I did mention this occasion, and he replied on a postcard (6 July): ‘I was v. interested in what you say about the E major chord at the end of ‘Virgo Virginum’!’

On 4 November 1978 Lennox and Freda spent a weekend with us, and he played the result of his trial scene. This was Barbara’s escapist aria ‘Give me the golden age’, the first music composed for Faldon Park, and I found it very moving. He was now determined to tackle the opera seriously (9 November). At his request I sent him a page of rearranged dialogue for the first scene; I also have a slightly different draft in his hand. He replied (5 April 1979) ‘Yes this suits me better. The first scene has been very difficult, but I think I’ve more or less got it now’. He had received ‘a very encouraging letter from George Harewood’. For the rest of the year the opera made slow but steady progress, though when staying with us in July 1979 he had a fall and was found to have broken four ribs. At one point some lines for Sir Digby that I had imagined as recitative flowered into an aria, and the whole first part of the scene in 1745, up to the quintet, went fairly smoothly, though Lennox had some trouble with the trio.

The Arts Council award of a grant came through on 7 December 1979: £6000 to Lennox and £2000 to me, half to be paid at once and the other half on completion of the opera. Officially it was commissioned by the English National Opera with funds provided by the Arts Council. The contract was signed in July 1980.

In April 1980 Lennox told me he had been side-tracked by two further commissions, a motet for the Benedictine celebrations20 (a beautiful piece which I first heard at his Requiem Mass in March 1990) and a Magnificat for Chichester Cathedral. But he was soon back to work on Faldon Park, and several letters contain detailed suggestions for adjustment in the exchange between Martin, his parents and the Fothergills. Early in October he asked for more lines – ‘largely exclamatory but no long words if possible. At this stage the characters needn’t express anything particularly relevant!’– to bring the quintet to an end. I sent him some, but he replied on the 16th: ‘Don’t worry about what I asked you for – I will go ahead as best I can but I find crowd scenes very difficult’. Eight days later he was in difficulties over the entry of the Colonel and the militia, where he said he had been stuck for some time because he could not see it as it would be on the stage; yet his proposed solution – the neighbours etc entering severally towards the end of the quintet, the militia marching in as a body to band music in the orchestra, the Colonel after standing them at ease turning to his relations and then moving into his aria – was exactly what I had envisaged. Meanwhile he had begun the full score. He also wrote a new orchestral Prelude about this time, and – perhaps a little later – began to set the opening scene of Act II.

By March 1981, ‘getting rather tired of the Colonel, but at the same time unable to move into the repetition of “O let the fame of Blenheim field” and join it to Barbara’s appearance’, he had composed Martin’s solo, ‘I think I saw you long ago in dreams’, at the start of the finale. He then returned to the Colonel, whose aria he considered very melodic and good to sing but too long, and was struggling with the repeat of the choral refrain ‘O let the fame’. Apparently he wanted to write new music for this (I had imagined the original melody varied by extra counterpoint and perhaps extended at the end), ‘but I can’t find the right notes’. He asked for a little verse for Barbara at her entrance (‘it might get me going again’), and I sent him four lines. He wrote a most beautiful instrumental passage for her appearance, but when we looked for it later it could not be found.

After this letter (9 March) there is a gap of more than two years in our correspondence (we were of course meeting regularly), but two occasions are vivid in my memory. Lennox proposed Colin Graham as producer (and warmly approved my suggestion that Felicity Lott should be cast for Barbara). Accordingly a meeting was arranged at Lennox’s house on 21 November 1981 at which Colin and Sheila MacCrindle of Chester’s21 were present and Tom Wade of the ENO staff played through the vocal score as far as it went (near the end of the Colonel’s aria, before the second refrain). There was a long discussion of many aspects of the opera. Sheila made some notes, and I gave my views in a long letter to Lennox the following day. Among the suggestions, many of which came from Colin, were: (i) that the two baronets should be played by the same singer (which would require the elimination of the Skiptons from the Act II transformation scene); (ii) that the chorus should be omitted, except for the militia, where they would be TTBB only; (iii) that Barbara should be glimpsed fleetingly, with appropriate frisson music, between the quintet and the entry of the Colonel and militia (I was afraid this might devalue her appearance after the Blenheim aria); (iv) that Lady Skipton should faint at the ‘apparition’ (if so, Martin must take no notice; his attention is concentrated on Barbara from the moment he sets eyes on her); (v) that there should be a scene for Barbara and Eleanor in Act II. I agreed to this, but it was never written.

I was very much against the elimination of the chorus from the first transformation scene, since, as I wrote to Lennox:

(i) The audience has to be apprised immediately of two different things, the general panic caused by the approach of the Pretender’s army, and the Skiptons’ private troubles with Martin. If Sir Bartholomew and his wife are the only persons present, it is difficult to dramatise this effectively. (ii) The chorus makes for variety of texture and contrast. We need this, especially in a big theatre like the Coliseum. (iii) While I appreciate Colin’s idea of Barbara as it were drawing the Skiptons out of the past, I think the change here should be abrupt, not gradual. We have a gradual change back in Act II. The audience needs a jolt – a sudden realisation that they are in the 18th century. The chorus could be small, not the full complement …. Then the appearance of the full chorus at the two entrances of the Colonel with the militia would be more effective.

My other concern was the point at which Lennox got stuck, the end of the Colonel’s aria.

The trouble here, it seems to me, is that you have made the Colonel too soulful and emotionally self-indulgent (though with beautiful music!), when he should be extrovert, military, patriotic and not over-endowed with imagination. Lines 1-6 of the second stanza of the Blenheim song represent a transitory mood. I feel he should revert to type in the next couplet,

But we who lived had drained upon that scene A fiery draught yet coursing through my blood (N.B.!)

and from then on the music should have a long sustained crescendo or accelerando (metaphorical, if not literal) up to a climax at ‘O Englishmen, remember Blenheim field’, capped by an exuberant entry of the chorus.

The lines in which everyone reacts to the ‘ghost’ could be re-arranged as he thought fit, with some new ones if necessary, but I was still convinced that the chorus, who are superstitious and ignorant, should at first mistake Barbara for the Pretender. I ended: ‘Needless to say, the final decision rests with you. I begin to feel the shades of Boito and Hofmannsthal looking over my shoulder: it makes me feel rather uncomfortable!’

The second occasion I remember was a run-through at the Coliseum on 24 February 1982 in the presence of George Harewood, Edmund Tracey, Mark Elder22 and his deputy, and Robin Boyle23 and Sheila MacCrindle of Chester’s. Victor Morris and Tom Wade played the music on two pianos, one taking the voice parts. The vocal score stopped at the same point as before: the music for Barbara’s entry and the opening of the final scene for her and Martin had not been incorporated. Mark Elder looked at the fully scored opening of the opera and remarked on the neatness of the instrumental joins. I explained the plot in detail, and Lennox exclaimed in alarm at the prospect of both a quintet and a septet in Act II. I promised to do what I could to ameliorate this.

It is obvious to me now that Lennox’s final illness (Alzheimer’s disease) had already undermined his concentration; indeed it must have begun its deadly work some time earlier, before the November meeting. I was puzzled that he had stuck at a point that seemed much less problematical than many that he had surmounted earlier. It was the climax of the first act; the characters were established, and I would have expected the music to come comparatively easily. We had several long sessions in the next eighteen months, at Hambledon and Warwick Avenue,24 but I do not think any progress was made. Not that he relaxed his efforts: he began to set passages over and over again, forgetting what he had already done and sometimes giving words to the wrong character. He lost some sections that he had sketched or fully written. One of my visits to Warwick Avenue was devoted to sorting out a jumble of fragments that had become hopelessly confused and sometimes mixed up with music for other works.

Lennox’s last letters to me make sad reading. On 13 July 1983 from Cheltenham:25 ‘I fear that you will have given up seeing Faldon Park finished, but the truth is that I had a period of great difficulty and inability to get going – that side of things having seemed to dry up.’ However some fine performances of Ruth26 had inspired ‘a deep drive to get back to composition again and [I] am looking forward to working once more’. On 16 November 1983:

I have only rather disappointing news to give you about Faldon Park. The truth is that I’ve been having to cope with bad loss of memory not unusual at my age, but making creative work almost impossible or at least very difficult. I’ve had to stop for the time being.

He had hopes of a very good doctor, and longed to start again. He had enjoyed reading my Listener article (on his operas in connection with a broadcast of Nelson), but could not remember what I said. On 14 March 1984: ‘I’ve been very ill and quite unable to write to friends, still less to write any music’. However the tide had turned at last, and he was beginning to lead a more normal existence. ‘I don’t know whether I shall ever be able to write any more music but I’m hoping to try before long.’

That was his last letter to me. When he and Freda stayed with us in July (1984) his condition was painful to behold. He would sit at a table and offer to play, as if it were a piano. When we dined with him and Freda he would have rare lucid moments, but for most of the time he either remained silent or spoke a few words that had no relevance to what we were talking about. I last saw him on 22 May 1988, when a concert of his music organised by English National Opera and Chester Music was given at St Mary’s, Paddington Green, in honour of his 85th birthday, followed by a buffet supper for a large gathering of his friends at his home in Warwick Avenue. His mind was worlds away, but Freda said he recognised me.

At the concert Martin’s aria [from Faldon Park], ‘You married couples are all the same’ was sung by Edward Byles. I was not expecting it, and was assailed by a host of bitter-sweet memories. Had Lennox managed to finish the first act something capable of performance might have been saved. As it was, an immense amount of effort had gone for nothing. I have sometimes reproached myself for not having pressed him more frequently or more urgently during the nearly twenty-five years that elapsed between his initial enthusiasm and his assumption of the ENO commission, when he was not at the height of his powers. But although I was convinced – and am still convinced – that the opera would have added greatly to his achievement and contributed something of permanent value, I could not bring myself to do so. I was afraid of trespassing on his good nature and taking advantage of his friendship. The collaboration, when it did begin, was immensely happy, with never an angry or even an impatient word. But it was too late.