Lennox Berkeley’s neglected ‘Piano Concerto’

John France champions one of Lennox Berkeley’s hidden treasures, the ‘Piano Concerto’.

Many years ago (probably around 1972), I bought the Pye Golden Guinea album (GSGC 14042) featuring orchestral music by Lennox Berkeley, Alan Rawsthorne and Peter Racine Fricker. It was very much ‘on spec’, as I could not have conjectured what these works would have sounded like, never having heard any music by any of these three composers. I guess that it was simply because I ‘clocked’ it as 20th century British music that I made the purchase, but it may have appeared a little more daring than the records I had been buying at around that time, which included Elgar’s Cello Concerto and Vaughan Williams’s Sea Symphony.

The three works on this Golden Guinea LP were Berkeley’s Serenade for Strings, op. 12 (1939), Rawsthorne’s Concerto for String Orchestra (1949), and Fricker’s Prelude, Elegy and Finale (1949). It was originally released in 1965, and the music was performed by the Little Orchestra of London, under the baton of Leslie Jones. I immediately fell in love with Berkeley’s Serenade, which has remained a firm favourite ever since.

The Serenade remained the only Berkeley work in my ever-growing record library – until one day in 1978, I walked into Banks’ Music Shop in York (a great place in those days, presided over by the formidable Miss Banks, but sadly depleted now). There I spotted the Lyrita recording of the Piano Concerto in B flat major, op. 29, with David Wilde and the New Philharmonia Orchestra. It was bought immediately, despite the high price of £3.46 (about £20 at today’s value) and became an instant hit with me. Ever since I have considered it to be one of the most accomplished examples of this genre written by an English composer.

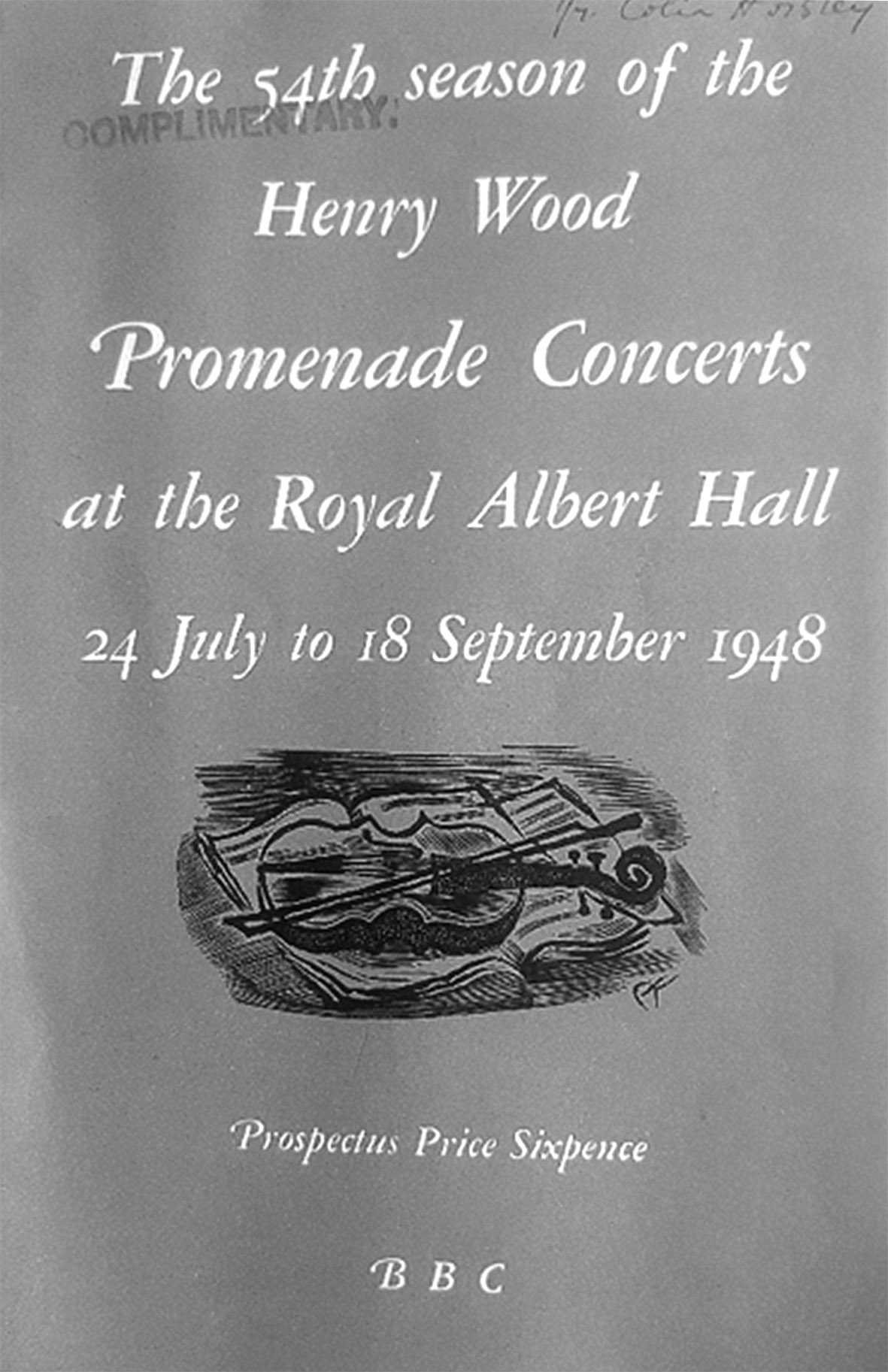

Anyone writing about Lennox Berkeley’s music is beholden to Peter Dickinson’s magisterial The Music of Lennox Berkeley.1 A case in point is Dickinson’s extensive study of this Piano Concerto (pp. 76–84). I do not wish to repeat that detailed analysis here. I want to dig a little deeper into the reception history of the work, with special emphasis on the premiere at the Proms in 1948, and the performance at the International Society for Contemporary Music (ISCM) in Palermo, Sicily, the following year. Additionally, I intend to investigate the two recorded versions of the Concerto. Finally, I will include a short note about the work’s dedicatee, and first soloist, Colin Horsley.

The 1940s saw a large amount of music from Berkeley’s pen. This included the Symphony [No.1], op. 16 (completed 1940) and the Divertimento in B flat op. 18 (1943). His most prolific achievement was in chamber music. Major contributions at this time included the String Quartet No. 2 op.15 (1940), the String Trio op. 19 (1943) and the Sonata in D minor for viola and piano op. 22 (1945). Three of Berkeley’s most important works for piano solo were written at this time: the Piano Sonata in A major op. 20 (1945), the Six Preludes op. 23 (1945) and the Three Mazurkas op. 32/1 (1949).

The most significant event for Lennox Berkeley during 1948 was the birth of his first son, Michael, on 29 May. From a musical perspective there were four important premieres. On 4 April Kathleen Ferrier gave the premiere of the Four Poems of St Teresa of Avila op. 27. On 31 May Berkeley’s fourth film score, The First Gentleman, starring Jean-Pierre Aumont, Joan Hopkins and Cecil Parker, went on general release in cinemas; this was a tale of intrigue and romance involving the Prince Regent’s daughter, Princess Charlotte, and Prince Leopold of Saxe-Coburg. On 31 August the Piano Concerto in B flat major was given its premiere at the Proms. And on 13 December the Concerto for two pianos and orchestra op. 30 (1948) was premiered at the Royal Albert Hall, with the soloists Cyril Smith and Phyllis Sellick.

On 14 December 1946 Lennox had married Freda Bernstein (1923–2016), and, in his book about the Berkeleys, Tony Scotland explains that just as the Stabat Mater op. 28 and the St Teresa Poems op. 27, both written in 1947, celebrate the composer’s faith, the Piano Concerto ‘reflects the new sense of optimism which his marriage had brought.’ 2

We are fortunate in having some information about the genesis of the Concerto in an interview with Colin Horsley recorded by Peter Dickinson on 30 November 1990. In it Horsley recalls that:

Val Drewry [a pianist who was at that time producing chamber music programmes in the BBC Music Department] and I got together and decided to commission a concerto from Lennox. It’s really a chamber concerto with Mozart at the back of his mind. I remember him saying that K. 503 in C was one of his favourites: the unisons were so beautiful, and in Lennox’s slow movement you have them.3

Several programme notes for Lennox Berkeley’s Piano Concerto in B flat major exist for both concert performances and both recordings, and Peter Dickinson’s analysis and discussion of the work can be consulted in his The Music of Lennox Berkeley. Berkeley himself has written of the Concerto:

In the spirit of the music and the shape of the movements, it has more affinity with Mozart than with the concerto writers of the nineteenth century, though of course there is no kinship with the Mozartian idiom. That sense of struggle, of a trial of strength between piano and orchestra which we get in a typical nineteenth-century work is absent; the manner is rather that of a dialogue between the two, the one commenting or enlarging upon what has been proposed by the other. Thematic material and the decoration are shared more or less equally between soloist and orchestra. The percussive quality of the piano has on the whole been avoided in favour of the melodic side, partly because an excessive use of the former in recent times has robbed it of all freshness, partly because it would not in any case suit the style of the music. The form of the movements is simple and requires no explanation.4

Summing up the progress of the Concerto, the musicologist and broadcaster Julian Herbage pointed out that each of the three movements ‘concentrates on a different aspect of our appreciative faculties. The first presents the intellectual argument, the second evokes our emotional response, while the third bubbles over with an exuberant gaiety.’ 5

The world premiere of the Concerto was given at the Royal Albert Hall, on Tuesday 31 August 1948, with the London Symphony Orchestra conducted by Basil Cameron, and Horsley as soloist. The concert opened with Mozart’s ubiquitous Serenade, Eine kleine Nachtmusik K. 525 (1787). This was followed by the Berkeley. After the interval, Prommers heard Dvorak’s Symphony No.7 in D minor op. 70 (1885), Ernest Chausson’s Poème for violin and orchestra op. 25 (1896), and two extracts from Hector Berlioz’s opera Les Troyens (1856-58): the ‘Chasse royale et orage’ and the ‘Marche troyenne’. The violin soloist was Yfrah Neaman.

One of the most succinct reviews of Berkeley’s Piano Concerto appeared in the Daily Herald, where ‘D. M.’ simply stated that ‘The three short movements are conceived as dialogues treating the piano as an extra orchestral instrument, thus avoiding any feeling of rivalry. The lyrical slow movement is the most intimate of conversations.’ It added that Colin Horsley ‘…played the piano part with great skill and obvious affection.’ 6

F. Bonavia for the Daily Telegraph gave the Concerto a mixed review. He thought that ‘Mr Berkeley uses the solo instrument well, and the orchestral score, very much reduced in the brass department, has a clearness by no means common nowadays.’ The thematic content of the Concerto displayed ‘character and novelty and … moments of austere beauty.’ On the negative side, Bonavia, in some confusion, considered that ‘the process of clarification [of what?] is not carried far enough’. He wrote, ‘Mr Berkeley seems to accept too readily a compromise that deprives his interesting work of unity of style and form.’ I can only imagine that this refers to the eclectic nature of the Concerto: on the one hand nodding towards the romantic, and on the other to the vagaries of French neo-classicism, with hints of Mozart. 7

The Times critic – possibly Frank Howes – thought that Berkeley, ‘a mature and profound artist’, had created a ‘significant product.’ It was not conceived on the ‘heroic scale’ of other concerti in that key, such as Brahms’s second, Tchaikovsky’s first or Arthur Bliss’s, but scored for ‘a small but ingeniously employed orchestra’. He thought the ‘climaxes are well handled’ and that the ‘texture throughout is lucid.’ The scoring for piano and orchestra was proportionate, so the soloist was never drowned out. The piano part was ‘deft’ and used ‘the whole range of the keyboard with [a] well-contrasted range of tone-colour.’ The soloist, Colin Horsley, had ‘carefully struck the right balance between classical and romantic playing …’ 8

Finally, The Musical Times critic, ‘R. C.’ [Richard Capell?], noted that:

The first performance of Lennox Berkeley’s Piano Concerto … provided new proof of this composer’s talent. In the use of harmonic devices and rhythm, in the invention of unusual and telling melodic lines, in the effective manner in which the parts of soloist and orchestra are joined or contrasted, Mr. Berkeley shows very uncommon skill. The scoring never misses its point, and there are no lapses of taste…The Concerto was most admirably played by Colin Horsley, to whom it is dedicated. 9

If there is one subject of modern music that demands a detailed study it is the impact of the International Society for Contemporary Music (ISCM). Since its first Festival in Salzburg in 1923, the ISCM has held an annual Festival in various worldwide locations. There have been 92 such events, with only the war years of 1940 and 1943-45 creating a hiatus. The 2020 World Music Day was due to have been held in Auckland and Christchurch in New Zealand but had to be cancelled because of the Covid pandemic.

For the 1949 event each country chose representative compositions to be submitted to the International Festival Jury. In England the local panel included William Alwyn, Anthony Bernard, Roberto Gerhard, Constant Lambert, and Bernard Stevens.10 The submitted works included Berkeley’s Piano Concerto in B flat major, Benjamin Frankel’s String Quartet No. 3, op. 18 (1947), Alan Rawsthorne’s Violin Concerto [No.1] (1948), Humphrey Searle’s Fuga Giocosa for orchestra (1948), and Phyllis Tate’s Sonata for clarinet and cello (1947). Additionally, two pieces by émigré composers then resident in England: a certain K.B. (not H.D.) Koppel’s Symphony for string orchestra (c. 1948) and the Hungarian Mátyás Seiber’s Fantasia Concertante for violin and string orchestra (1943-44). The International Jury subsequently chose just three British works for the 1949 Festival: the Searle, the Seiber and the Berkeley.

The Piano Concerto was performed on Tuesday 26 April 1949 at the majestic opera house in Palermo. Once again Horsley was the soloist, and the Rome Radio Orchestra was conducted by Constant Lambert. Other works in that concert included Searle’s Fuga Giocosa, the Symphony No. 2 in C for large orchestra, op. 15 (1942-46) by the Czech composer Miloslav Kabeláč and the ‘Second Suite’ from Thyl Claes (1945) by the Russian Wladimir Vogel.

I was unable to find an online review of this concert in the Italian press archives. But of the English reviews, Frank Howes writing in the Musical Times was clearly unimpressed. The Vogel, he wrote, was ‘ideological and doctrinaire (and therefore a bore)’, Searle was not mentioned, and Lennox Berkeley’s Concerto ‘failed to make much impression.’ 11 To be fair, Dickinson explains that despite successful rehearsals in Rome, the piano was in poor fettle, and ‘…Lambert in poor health…was the worse for wear with drink.’ 12 On the other hand, for Howes there was ‘no doubt about a war symphony by the Czech, Miroslav Kabeláč, a fine piece of music of obvious sincerity.’ 13 Apart from a single recording, this last work has virtually disappeared. Interestingly, the British submissions have also vanished from the repertoire, although single recordings exist of the Frankel, the Rawsthorne and the Seiber.

To my knowledge, the full score of Berkeley’s Piano Concerto in B flat major has never been engraved and published, but a two-piano reduction was published by J. & W. Chester Ltd. in 1951, priced 12/6d. Reporting on this publication, I. K. [Ivor Keys], writing in the academic journal Tempo, suggested that:

‘A concerto in the strict sense . . . both gay and brilliant without necessarily being profound or aiming at dramatic effects’. One might well apply this description by Ravel of his own concerto to Lennox Berkeley’s Concerto. It is far removed in its winning clarity – and indeed its comparatively easy solo part [!] – from the romantic and post-romantic sludge. On the other hand, it is not finicking, and it contains some good tunes, notably the disarmingly pastoral one in the slow movement, and the sturdy echo – or even development – of Sibelius in the last ... 14

The Austrian musicologist, composer, and conductor, Hans Ferdinand Redlich (1903-68) submitted a major essay to the short-lived journal, Music Survey (1947–1952), about Lennox Berkeley. Turning to the Piano Concerto in B flat, Redlich notes that Berkeley ‘courageously endeavours to reconcile the rigid demands of traditional cyclic sonata form with the vagaries of his own weakened tonal feeling’, which involves finding ‘valid substitutes for the customary modulations and inter-relations of basic harmonies.’ This suggests that conventional sonata form – exposition, development, and recapitulation – models are being replaced with thematic material that is intended ‘for variational treatment or canonic imitation.’ None of this means that Berkeley does not rely on Romantic pianistic gestures, and Redlich notes that ‘passages from Chopin, Field and Cramer … act frequently as archaic blueprints …’ The remainder of Redlich’s essay elaborates on this compositional process. Works examined include the Stabat Mater, op. 28, the Four Poems by St Teresa, op. 27 and the Concerto for two pianos, op. 30. 15

In his detailed discussion of the Piano Concerto in B flat, Peter Dickinson makes some interesting general comments. He points out that the ‘effortless invention throughout the piano concerto is at Berkeley’s highest level’ and that ‘Berkeley’s approach to sonata form is always unconventional and serves him well in chamber music too’. In the final movement, he writes that ‘Berkeley avoids any kind of pompous finale by setting the tone with a perky theme that would not be out of place in Prokofiev or Shostakovich.’ Dickinson cites Lennox Berkeley’s own opinion of his Concerto later in his life: ‘I still quite like the piece, though there are things I would do differently and, I hope, better now.’ (Berkeley Diary, August 1975). I agree with Dickinson’s conclusion that ‘this is a mistaken impression – Berkeley could not have improved on the Piano Concerto.’ 16

In the 1970s, Lyrita were expanding their record catalogue, at, for me, an alarming rate. There was a time when new LPs seemed to be issued every week. It was hard to keep up, but I did. I still have many of these vinyl discs, despite having replaced them with CD copies. Lennox Berkeley has been well served by Lyrita. Recordings include the first three symphonies, the Stabat Mater op. 28, the Sinfonietta, op. 34 (1950), some chamber music, a selection of piano pieces and an album devoted to the shorter orchestral works, comprising the Divertimento in Bb, the Serenade for strings, the Partita for chamber orchestra, op. 66 (1966) and the Britten-Berkeley Mont Juic Suite, op. 9 (1937).

The Piano Concerto in B flat major was issued on Lyrita SRCS 94 in 1978, with David Wilde and New Philharmonia Orchestra conducted by Nicholas Braithwaite. In a diary entry on 24 August 1975 the composer writes about the recording at Walthamstow Town Hall:

David Wilde was the soloist and I thought him really first class. His playing is deeply musical, going much further than virtuosity, though his technique allowed him to be completely relaxed so that he only had to think about the music. It was in the technically easiest parts that his musicianship showed up the most – beautiful cantabile tone and variety of tone-colour…’ 17

Reviewing the Piano Concerto in B flat in The Gramophone, ‘M.M.’ (Malcolm MacDonald), considered that ‘no passage in it could be taken for the work of any other composer…’ He thought the music ‘here and there [sounds] romantic without apology.’ David Wilde, he said, gives ‘the cleanest and most impeccable of performances and is kept in very good balance with the almost equally impeccable orchestra …’ MacDonald was also impressed with the Symphony No. 2, characterised by ‘sophistication, clarity, and [the] general avoidance of over-statement.’ And he concluded that ‘this is a record to treasure.’ 18

In America the critic Maurice Jacobson provided a somewhat negative review for Stereo Review. He began by suggesting that Sir Lennox Berkeley ‘... is not just urban, but conspicuously urbane, as his admirers never tire of pointing out.’ Jacobson qualified this by suggesting that ‘If you enjoy the sort of music that most prominently exhibits Gallic sophistication and charm – like, say, Walter Piston’s minor works … or those of Jean Françaix – Berkeley could be to your taste.’ The comparison of these two composers with Berkeley may be apposite: all three were pupils of Nadia Boulanger in Paris. Jacobson concludes his review conceding that ‘this new record of his Second Symphony and (so far only) Piano Concerto … presents decent performances in good sound.’ But the sting is in the tail: ‘Personally, I am left cold by this accomplished but essentially pointless music, as well as repelled by the paradoxically bloodless vulgarity that tarnishes its wearisome “good taste”.’ 19

For me, it is the ‘good taste’ that makes so much of Berkeley’s music such an antidote to a lot of the avant-garde music being composed in the late 1940s and 1950s.

In 2002, Chandos Records began a remarkable Berkeley Edition of six CDs, featuring the music of father and son, Lennox and Michael. Each disc included works by both composers. The series provided recordings of Lennox’s four symphonies, the Sinfonia Concertante op. 84 (1972-73), the Serenade for strings, the Concerto for two pianos, Voices of the Night op. 86 (1973), the Four Poems of St Teresa of Avila. The Piano Concerto was released on CHAN 10265 (2004), with Howard Shelley as the soloist and the BBC National Orchestra of Wales conducted by Richard Hickox.

Reviewing the Chandos disc in The Gramophone, Peter Dickinson acknowledged that the late 1940s was a ‘vintage period’ for Lennox Berkeley, and wrote that the St Teresa Poems were conceived with the ‘incomparable sound of Kathleen Ferrier’ in mind. Dickinson considered that the Piano Concerto ‘…receives an impeccable performance thanks to the superlative musicianship of Howard Shelley and Richard Hickox, who both understand the music completely.’ Here the ‘tunes are memorable, the scoring Mozartian and it is incomprehensible that this outstanding British Piano Concerto has not become a repertoire standard.’ 20

So which version of this Piano Concerto in B flat major is the preferred option? From a personal perspective, there is always a tendency to favour the ‘first’ recording that I heard. I still recall being impressed with the elegance and sophistication of David Wilde’s Lyrita performance, and it did serve Berkeley enthusiasts well for nearly 30 years. On the other hand, I agree with Peter Dickinson that Shelley’s account ‘consistently sparkles’ and excels with the ‘rapt slow movement.’

Lennox Berkeley devotees will demand both versions of this work in their record libraries. I do wonder, though, if there will be another recording of this Piano Concerto any time soon.

Many composers of the British Isles have written piano concertos over the past 200 years or so. These begin with the well-crafted examples by John Field and William Sterndale Bennett and progressing down through the years to Thomas Adès’s Concerto premiered in 2018. Stylistically, they have varied from romantic to avant-garde, by way of neo-classical and post-modern. Typically, they have two things in common: they are rarely recorded and hardly ever performed in the concert hall. To be sure, there have been some innovative recordings made of this genre over the years by Naxos, Chandos, Hyperion amongst others. But think on this: currently (2 November 2020) there are some 130 recordings of Rachmaninov’s Piano Concerto No. 2 in C minor op. 18, 116 of Grieg’s Piano Concerto in A minor op. 16 and a whopping 187 versions of Tchaikovsky’s Piano Concerto in B flat major, op. 23 (figures according to the Arkiv Music catalogue, but some may be re-packagings).

It is time that concert promoters and record companies looked to the impressive achievements of British composers rather than relying on a small number of guaranteed money-spinners. Lennox Berkeley’s Piano Concerto in B flat major op. 29 is a case in point. Only two recordings of this remarkable work have been issued, and few can recall a recent live performance. Maybe one day our resident orchestras will skip yet another performance of a warhorse and oblige with one of many remarkable British piano concertos that are just waiting to be heard.

Select Bibliography

Craggs, Stewart R., Lennox Berkeley: A Source Book (Ashgate, Aldershot, 2000).

Dickinson, Peter, The Music of Lennox Berkeley (The Boydell Press, Woodbridge, 1988/2003).

___ (ed.), Lennox Berkeley and Friends: Writings, Letters, and Interviews (The Boydell Press, Woodbridge, 2012).

Scotland, Tony, Lennox and Freda, (Michael Russell, Norwich, 2010).

Files of the Daily Herald, The Times, Daily Telegraph, The Musical Times, Tempo, Stereo Review.

Notes on gramophone records, and CD liner notes, etc.

Discography

Piano Concerto in B flat major, op. 29, David Wilde, piano; New Philharmonia Orchestra/Nicholas Braithwaite, Symphony No.2 London Philharmonic Orchestra/Nicholas Braithwaite Lyrita SRCS 94 (1978) LP; re-released on SRCD 250 (2007) CD.

Piano Concerto in B flat major, op. 29, Howard Shelley, piano, and Four Poems of St Teresa of Avila, with Michael Berkeley, Gethsemane, Fragment, Tristessa, BBC National Orchestra of Wales/Richard Hickox Chandos CHAN 10265 (2004).