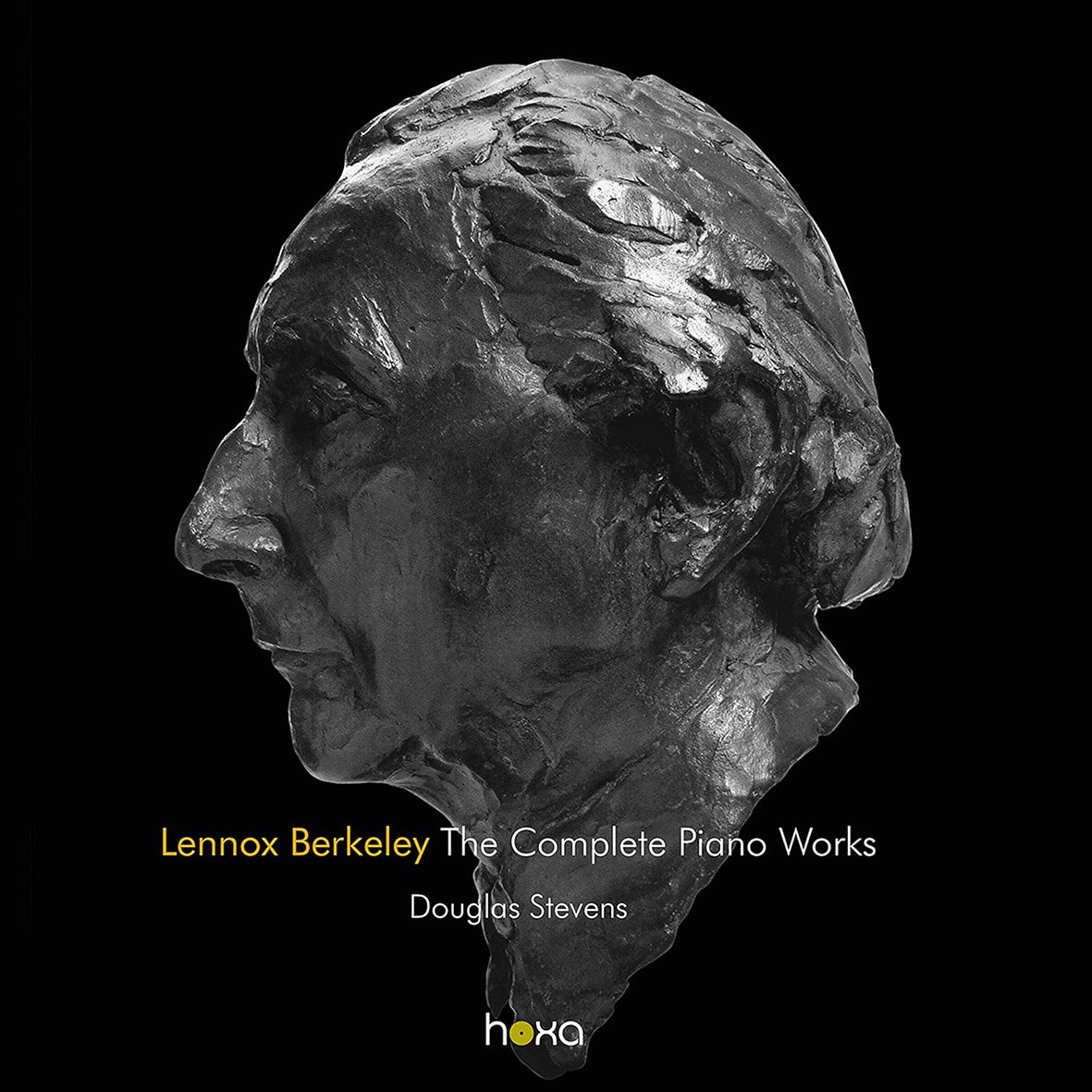

Douglas Stevens’ album of Berkeley’s piano music

Peter Dickinson reviews Douglas Stevens’ new recording of Bertkeley’s piano music

Members of the Society don’t need to be told that Lennox Berkeley was one of the finest British composers of piano music in the last century, but this two-CD set, which was a pleasant surprise, demonstrates this incontrovertibly. The output is varied with groups of short pieces, single studies, and the eloquent Sonata of 1945. This work was a landmark, written for Clifford Curzon who hardly ever played it, taken up by Colin Horsley who dedicated himself to Berkeley, giving many international performances of the Concerto, commissioning the now unknown Concerto for Piano and Double String Orchestra (Op. 46), as well as playing the solo works. He told me he did about ninety performances of the Six Preludes and gave me a lot of detail in his interview in my Lennox Berkeley and Friends. The Sonata was practically an avant-garde document in British music of that time, with Berkeley at the height of his powers. I got to know the work in my last year at school but never performed it complete: a copy of the bill from Miller’s Music Shop in Cambridge is reproduced in Lennox Berkeley and Friends. In those days you could go into any good music shop and find all the latest publications. Those light blue covers of the early editions, although the wrong blue for an Oxford man, seemed to symbolise something about Berkeley’s appeal. All Berkeley’s music is lyrical and there are many pieces in the piano output with memorable melodies. What is incomprehensible is that pianists neglect this repertoire in favour of the usual run of classics endlessly repeated.

Douglas Stevens is a virtuoso, and it seems extraordinary that this release may be his first appearance on CD. He did a PhD on Berkeley at the University of Bristol [Lennox Berkeley: a Critical Study of his Music, 2011] but unfortunately it has not been published. That experience must have left him wanting to do justice to the piano works. There have been several recordings over the years – Colin Horsley on LP (later CD), Raphael Terroni, Christopher Headington (an early pupil), and, most recently, Margaret Fingerhut. None of these is complete.

Perhaps Stevens’ greatest strength is his phenomenal technique. He makes light of the two sets of concert studies with all their intricate passage-work that never obviously repeats the layout of its figuration patterns. In fact, the dazzling effect of Stevens’ finger-work raises the second less impressive set to a new level. We are never going to hear the two sets of studies played better than this. The second set of Four Concert Studies is slightly slow; Horsley got this right, and is up to all the pyrotechnics of the last two in the set. There are numerous less frenetic delights with Stevens – the second of the Three Pieces, the ‘Berceuse’, is sheer perfection with a mesmeric atmosphere; so is Paysage, the last of the Six Preludes too. Berkeley played this himself and it’s close to a self-portrait. The Three Mazurkas, celebrating Berkeley’s love of Chopin, come off beautifully and Stevens usefully points out in his booklet notes that the late, singly published, Mazurka (Op. 101 No. 2), is clearly indebted to Chopin’s Mazurka in C# minor (Op. 6 No 2). Stevens introduces the second Berkeley ‘Prelude’ of the Op. 23 set, and mentions the C natural in the opening bar as ‘the chromatic neighbour note to the C sharp that also heralds the brief arrival of D minor seventh in bar 3’: fortunately, listeners are not expected to cope with much of this. He talks of Berkeley’s ‘relative obscurity’ and it may seem like this to younger people today, but the wealth of recordings speaks for itself. There are two, rare, editorial errors in the third ‘Prelude’: otherwise these are fine recordings.

Stevens is scrupulous in observing every nuance and dynamic mark throughout. This makes it disappointing to find that he has ignored Berkeley’s clear metronome mark in the ‘Adagio’ of the Piano Sonata and plays it far too slowly. Colin Horsley and, most recently, Margaret Fingerhut (on Chandos 2004) understood this movement better.

The Collected Works for Solo Piano (Chester, 2003) includes Three Dances from an untitled ballet score. The first one exists as a piano sketch, which I was able to use, and I arranged two more numbers from the still unknown ballet. It might have been worth including this attractive set which is very typical.

Of the juvenilia, the March (1924) has no mature characteristics, its opening perhaps suggested by the first of Vaughan Williams’ Songs of Travel; Mr Pilkington’s Toye (1926), in an adapted Scarlatti idiom, reflects, at an early stage, the interest in early music, its repertoire and instruments. Vere Pilkington, Berkeley’s flatmate at Oxford, possessed a harpsichord and Christopher Lewis has even recorded this piece – and For Vere (1927) – on his harpsichord CD (Naxos 2016); he’s also made an edition, and given first modern performances, of Berkeley’s Suite for Harpsichord (1930). For Vere shows Parisian bitonality as Berkeley was by now starting his studies with Boulanger.

First recordings are not indicated on the CD. These are March, Toccata, the later Four Piano Studies (1972) and Prelude and Capriccio (1978). Stevens conquers the difficulties of the Toccata effortlessly and makes out the best possible case for the later pieces too, written at a time when Berkeley was beginning to show some decline.

Stevens rightly claims ‘the remarkable individuality of Berkeley’s style attests to the way (his) influences became amalgamated into a unique compositional style’. His recording is more than ample proof of this, and all admirers of Lennox Berkeley must be grateful.