Lennox Berkeley’s Clarinet ‘Sonatine’

Clarinettist John Slack introduces Berkeley’s ‘Sonatine’ of 1928.

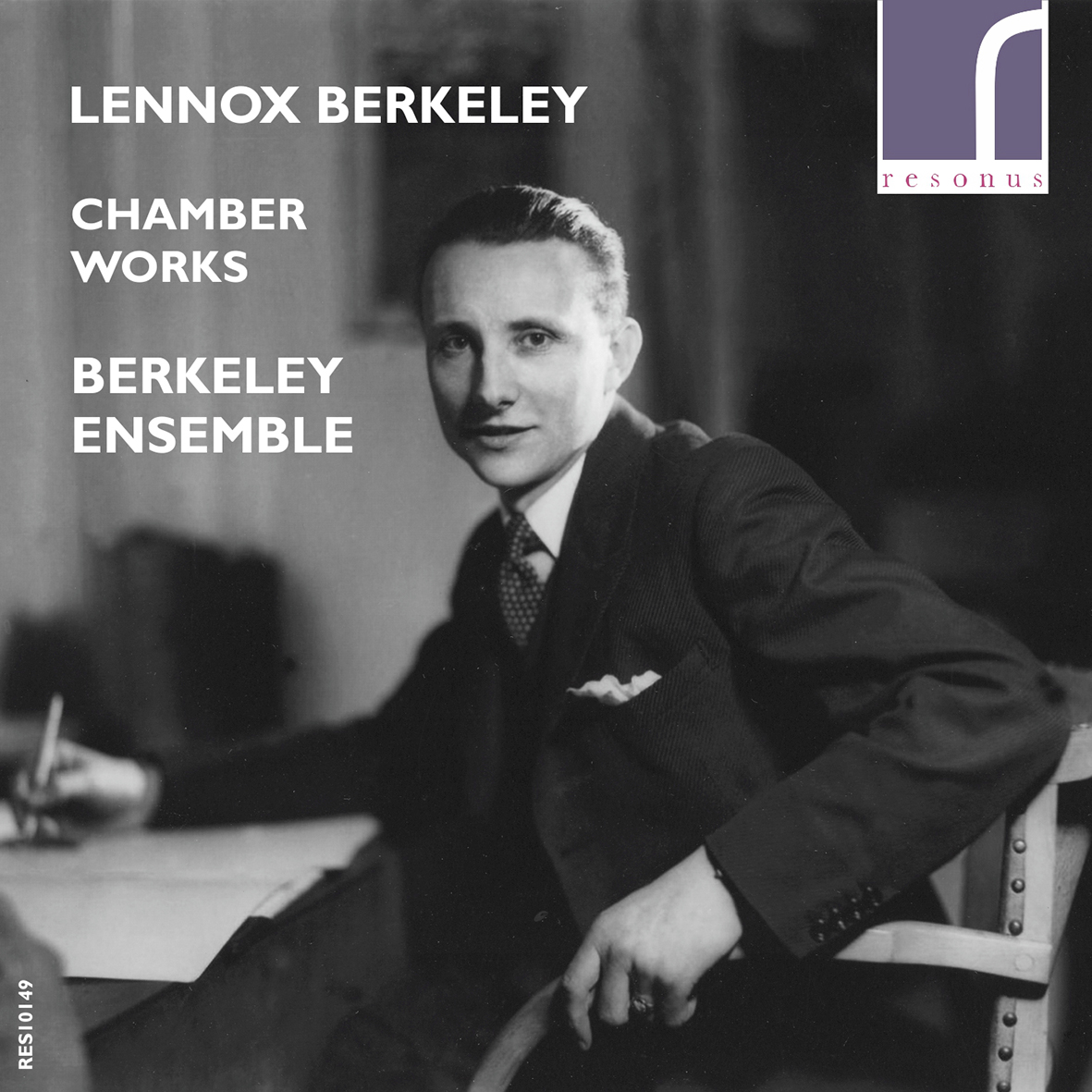

As many readers of this Journal will know, the Berkeley Ensemble was formed to explore neglected chamber music repertoire, in particular the abundance of works by British composers of the twentieth century. Lennox Berkeley’s String Trio and Sextet for Clarinet, Horn and String Quartet have been firmly in our repertoire since our first concerts in 2008, and it seemed natural, when discussing plans for our second recording on Resonus Classics, that we should turn to these two works to form part of a new survey of Lennox’s chamber music.

With excitement we set about researching other works that we had not yet explored or performed together. The Lennox Berkeley Society website proved to be an invaluable resource, and both Paul Cott (the Berkeley Ensemble’s artistic director and horn player, and a Lennox Berkeley Society Committee member) and I scoured the ‘Works’ section of the site looking for un-recorded pieces matching our instrumental line-up.

Among the tantalising offerings was the Stabat Mater, the recent revival of which we were happy to have been involved in.1 We were surprised to find that the Sonatine pour clarinette et piano dating from 1928 was not only unrecorded, but hadn’t even been published! Given the popularity of clarinet and piano works in general it was our assumption therefore that the Sonatine must be an incomplete sketch or, being a student work, of questionable quality. We turned out to be quite wrong.

With our researchers’ hats on we went to the British Library where Nicolas Bell, curator of Music Collections at the time, was extremely helpful in allowing us access to several of the hundreds of manuscripts acquired from the Berkeley family in 2014. Nicolas and the Berkeley family were quick to agree to our request for scans, photos were sent the very next day and pianist Libby Burgess (a regular collaborator with the Ensemble) and I played through the work. It was fascinating to discover the piece for the first time, in the knowledge that it would have received only a handful of performances at most since its première in 1928 by the great British clarinettist Frederick (‘Jack’) Thurston and pianist Gordon Bryan at the Aeolian Hall in London.

Our first impressions were overwhelmingly positive – this was a characterful piece, drawing inspiration from the musical world in Paris where Berkeley was studying with Nadia Boulanger at the time.

The searching and inquisitive main theme of the first movement is interspersed with a Stravinsky-esque march (reminiscent of The Soldier’s Tale), whilst the second movement is a tolling lament; the long clarinet lines punctuated by anguished outbursts foreshadowing the middle movement of Poulenc’s Clarinet Sonata which would be written some 34 years later. The third movement provides a rather fun whirlwind finale.

Gordon Bryan, writing in The Monthly Music Record in June 1929, claimed the Sonatine provided a definite advance in composition style for Berkeley, and noted the influence of Hindemith on the work and that the general effect was ‘novel and striking’. Bryan was also drawn, as was I, to the considerable use of bitonality in the piece, although a contemporary critic at the first performance accused Berkeley of having ‘caught some of the Paris tricks fashionable at the present moment’.

Following that first read-through Libby and I set to work preparing the Sonatine for recording, and we are indebted to Professor Peter Dickinson for his help in clearing up several queries we had with the score, including discrepancies in dynamics, articulations and tempo markings. Some of the writing for the clarinet does not lie so well under the fingers (particularly compared with the Sextet, written in 1955) but the practice required was certainly worth it. We have since performed the piece several times, in recital at the Dartington International Summer School & Festival in August 2015 and in private concerts in Somerset and London.

I am grateful to both the Lennox Berkeley Society and Chester Music for making the recent publication of the work possible,2 which will allow clarinettists, pianists and audiences to enjoy this joyful work more widely, and provide a worthy addition to the concert – and examination – repertoire for the clarinet.