Lennox Berkeley at the Proms in 1973

John France examines the reception of Lennox Berkeley’s ‘Symphony No 3’ and ‘Sinfonia Concertante’ at the Proms in 1973.

The 1973 Promenade Concerts were the last to have been planned by the legendary (or notorious, depending on your view) Sir William Glock. Despite having retired as Controller of Music at BBC Radio Three in the previous November, he had agreed to schedule this series of concerts presented by the new Controller, Robert Ponsonby.

There were several important British débuts during the 1973 season, including four BBC commissions: Thea Musgrave’s Viola Concerto, Priaulx Rainer’s Ploërmel, Nicola Lefanu’s The Hidden Landscape and Lennox Berkeley’s Sinfonia Concertante op. 84. A little bit of historical catching up was going on too: Ralph Vaughan Williams’s Towards the Unknown Region (1906) and Gustav Holst’s Hammersmith Prelude and Scherzo (1930–31) were also belated ‘novelties.’

The Lennox Berkeley 70th Birthday Concert was held at the Royal Albert Hall on Friday 3 August 1973. It was nearly three months after his actual birthday on 12 May. The concert began with Benjamin Britten’s ‘Four Sea Interludes’ from Peter Grimes (1945). This was followed by the world premiere of Berkeley’s Sinfonia Concertante for oboe and chamber orchestra, dedicated to the evening’s soloist, Janet Craxton. Immediately after the Sinfonia, the audience heard the Proms première of Berkeley’s Symphony No. 3 in One Movement (1969) op. 74, which had been given its world première at the Cheltenham Festival on 9 July 1969. After the interval, the only work was Tchaikovsky’s Symphony No.6 in B minor, the ‘Pathétique’ (1893). Raymond Leppard conducted the BBC Northern Symphony Orchestra (now the BBC Philharmonic).

Berkeley’s Birthday Prom was broadcast live on BBC Radio 3. In an interval talk on the wireless Dr Hugh L’Etang, Editor of The Practitioner, described ‘how ailing leaders have changed the course of recent history.’

The Sinfonia Concertante lasts for about 23 minutes. It was conceived in five relatively short movements, about which the composer wrote,

… though the solo instrument has the predominating part throughout, it has neither the character nor the usual form of a concerto. The emphasis is more on the oboe’s aptitude for melodic expression and expansion than on what it can offer as a vehicle for the display of virtuosity. (Liner notes, Hickox recording, Chandos CHAN 10022).

The work opens with a ‘Prelude’ played lento. It features some sinuous melodies that lead into an ‘Allegro’ which is often abrupt and strongly rhythmic. The third movement presents a contemplative ‘Aria’ during which the oboe plays in dialogue with the orchestra. This is followed by a delightfully pastoral ‘Canzonetta’, which seems to transcend musical history by introducing material that could have been penned by any one of ‘Les Six’ in the 1930s. This movement is written in ternary (three part) form, with an almost literal repetition of the opening music after a gently contrasting middle section. The finale juxtaposes music that is initially tense, with passages that are a little (but not much) more relaxed. At the end of this movement Berkeley has provided a challenging cadenza for the oboe written in a buoyant 5/8 metre.

The Sinfonia was commenced during the summer of 1972 and completed in March 1973. Lennox Berkeley had previously composed two works for Janet Craxton: Sonatina op. 61 (1962) and the Oboe Quartet op. 70 (1967).

Joan Chissell, reviewing this Prom for The Times (4 August 1973), recognized that it was appropriate to begin with Britten’s Sea Interludes as the two composers had been close friends since first meeting in Barcelona during the 1936 International Society for Contemporary Music Festival. Both men had compositions performed there: Britten’s Suite for Violin and Piano op. 6 (1934–35) and Berkeley’s Overture op. 8 (1934, now withdrawn). The immediate artistic outcome of their new friendship was the charming Mont Juic suite of Catalan dances which they heard in Barcelona. Each composer contributed two movements.

Chissell was impressed by the Sinfonia Concertante. She judged that the oboe was used ‘melodically and expressively’ rather than ‘show[ing] off.’ The scoring was ‘characteristically transparent’ with ‘much give and take in conversational exchanges.’ Each of the five movements ‘has its own piquant flavour.’ Like several commentators, Chissell felt that the most attractive section was the ‘disarmingly simple’ D major ‘Canzonetta’ which was ‘typical of the Gallic Berkeley.’ Bearing in mind that the early 1970s were at the peak of avant-garde excesses, she understood that ‘courage is needed to write such music now….’ As to the playing, the ‘malleable’ soloist, Janet Craxton was ‘in every respect worthy of the occasion.’ Finally, Chissell was impressed by the Sinfonia’s ‘fastidious craftsmanship’, and she noted that ‘its cool, alluringly wry sound won it an immediate welcome.’

Unfortunately, Joan Chissell said little about the Symphony No. 3 – just that its performance that night ‘must have been as strongly characterized and at the same time as finely integrated an account of Berkeley’s third symphony as any yet given in this 70th birthday year.’

A. E. P [Anthony Payne?], writing in the Daily Telegraph on 4 August 1973, enjoyed the ‘surprisingly wide emotional range’ of the Sinfonia Concertante which balanced ‘pastoral overtones’ and ‘hidden strength’, occasionally allowing the trumpets and horns to ‘suggest more monumental feelings.’ He too was ‘enchanted’ by the fourth movement, the ‘Canzonetta’.

A. E. P. considered that the Symphony No. 3 ‘embraces a considerable area of feeling.’ He accepted that ‘its taut, knotty language and forceful gestures aim more obviously high [than the Sinfonia] and its single movement makes a virile impression, moving without inflation or pretentiousness through high-tensioned, often ambivalent arguments to final resolution’.

The long-lamented Music and Musicians (October 1973) featured an extensive discussion of the two works by Meirion Bowen who considered that ‘the contrast between the Symphony No. 3 and the Sinfonia Concertante … was extreme.’ I disagree with Bowen that this latter work ‘was a throwaway effort, a five-movement salon suite that hardly engaged the attention, so unobtrusive was its musical material, so unadventurous its design’. On the contrary I feel that it is a minor masterpiece – one of the most approachable and engaging of all Berkeley’s works.

Bowen believed that Janet Craxton did her best with the piece, but ‘in sum it was a dozy affair.’ It is hardly surprising that Bowen admired the Symphony. In fact, he said, it made ‘one sit on the edge of one’s seat.’ He insisted that Berkeley had ‘faced squarely the challenges of twelve-note technique and produced a taut design’, much of which derives from the opening juxtaposition and ‘embellishment’ of two triads (based on six notes from the chords D minor and B major). Bowen noted that the outer sections indulge ‘cool and refined’ scoring, whilst the middle one ‘introduces fiery and dramatic rhetoric.’ Finally, the orchestra successfully ‘communicated’ the ‘logic and inevitability’ of the entire Symphony.

Meirion Bowen also contributed an important review to The Guardian (4 August 1973), in which he wrote that in comparison to the ‘gently appealing’ Sinfonia Concertante, the Symphony contained considerably more ‘argumentative power and sustained vision.’ This was conveyed ‘very convincingly’ by the orchestra. He pointed out that this work ‘involves a much larger orchestra than [the Sinfonia], but its textural diversity and cunning manipulation of thematic material in a continuous design, comprising various tempi, suggested what Berkeley could do at full stretch.’

His final paragraph is as pertinent in 2020 as it was 47 years ago. He writes, ‘We undervalue Berkeley, and I hope that those who heard this magnificent [symphony] for the first time will pursue their acquaintance further.’

Despite many excellent recordings, several important books and the sterling efforts of the Berkeley Society, Berkeley is still hardly well known to much of the musical public. It is a fate of many composers.

Andrew Porter wrote a major critique of the 70th Birthday Concert in the October 1973 edition of the Musical Times. Beginning with the Sinfonia Concertante, Porter felt that ‘Berkeley’s is a quiet voice saying things subtle but not tortuous, gentle even in assertion, and courteous at its most confident. But the sympathetic listener’s ear is caught by the play of his melodic and rhythmic fancy, which is the more fascinating for being temperate [and] unextravagant’.

In Porter’s opinion Janet Craxton displayed ‘lyric intensity’ in this ‘charming distinguished’ work. He writes that ‘the oboist sings throughout, sometimes with the decorative rapidity of a coloratura virtuosa but more often in smooth, shapely, yet unpredictably irregular periods.’

Turning to the Symphony, Porter sensed that

…[it] was given a more energetic and colourful (and very slightly faster) performance [by Raymond Leppard] than by the composer himself on the Lyrita recording. The sarabande at its heart still seems all too brief, and the insistent 6/8 of the final section very nearly outstays its welcome – not quite, for by an exuberant gesture it is suddenly cut short.

Richard Rodney Bennett’s review (Tempo, September 1973) of the Sinfonia Concertante is worth quoting in detail, and not only because he was a student of Berkeley at the Royal Academy of Music. He began by saying that it ‘showed all his most endearing qualities: freshness of invention, sure and imaginative formal craftsmanship, and above all an absolutely personal style.’

He continued by pointing out that

… there are some critics who, while accepting the presence of these virtues, would nonetheless make them the very grounds on which to damn the work with faint praise as tasteful, pallid, and pointless. But the civilized, civilizing qualities of Berkeley’s music are precisely what makes it strong enough to stand up to such criticism.

It is no surprise that a composer with Richard Rodney Bennett’s talent for creating memorable tunes, should have delighted in the universally admired ‘Canzonetta’. He writes that

… it is ‘merely the statement of a ravishingly simple, shapely and memorable tune – which I find I can still recall in its entirety, some time after the concert. This little ‘Canzonetta’ is already reason enough for accepting the work with delight.’

Like other critics, Bennett felt that the Sinfonia Concertante was ‘beautifully played’ by Janet Craxton and the orchestra.

This was to be the only occasion that either the Sinfonia Concertante or the Symphony No. 3 has been heard at a Promenade Concert.

It may be interesting to consider a few other key concerts of the Symphony No. 3 which took place between the world première in Cheltenham on 9 July 1969 and the Proms première in 1973. Writing of the first London performance in a packed Royal Festival Hall on 19 December 1971, Ronald Crichton (Musical Times, February 1972) drew attention to the prestigious programming with Tchaikovsky’s Pathétique and John Ogdon playing Rachmaninov’s Piano Concerto No. 4. Alas the Symphony seems to have been given a less than ideal account by the London Philharmonic Orchestra and their conductor John Pritchard. Crichton was surprised by ‘the weak string playing in the Symphony’s opening’ which did not reflect the composer’s demand for ‘explicit and strong contrasts.’ He thinks that it would have made a stronger ‘impression of cogency and lucidity … if the performance had been better prepared.’

On Thursday 22 March 1973, André Previn and the London Symphony Orchestra gave another performance of the Symphony No. 3 at the Royal Festival Hall, in a concert which included Rachmaninov’s ‘attractive, slightly astringent’ Symphonic Dances op. 45 (1940) and the ever-popular Violin Concerto in E minor op. 64 (1844) by Mendelssohn. The soloist was Itzhak Perlman. Robert Henderson writing in The Daily Telegraph (23 March 1973) reported that Berkeley’s Symphony was ‘short, concise and lucidly textured, [drawing] much of its strength and musical resilience from its very deliberate economy of matter.’ Echoing several reviewers, Henderson felt that the Symphony had been ‘pared away to its bare essentials, every note performing a precise, clearly audible function within its one, tautly argued movement.’ In an interesting comment he considered that the ‘long, finely-contoured string melodies and underlying momentum [create] an illusion of breadth far beyond that suggested by its actual time span’. It certainly seems a more expansive work than the duration alone would suggest.

Ronald Crichton, reviewing the same concert in the Musical Times in May 1973, found the Symphony No. 3 ‘an engaging one-movement work written on a note [tone] row of which for much of the time only half is used’, and thought that its ‘understatement conceals precise feeling and sense of direction.’ Previn’s performance, in Crichton’s view,

… was mostly good, but the first section needed both a little more bite and a more natural unfolding. In the 3/2 Lento there was a touch of alien romanticism. But the episode for three flutes in the first section and the whole of the final section, much tauter in effect than its cantering 6/8 initially promises, were delightful.

Crichton concluded his comments by calling for a revival of Berkeley’s first two symphonies.

Somewhat belatedly, the June 1973 edition of Music and Musicians carried a review by Richard Lawrence who reckoned that the Symphony No. 3 ‘turned out to be an attractive, unpretentious piece’. He was impressed with the ‘cool’ and ‘delightful’ scoring. On the other hand, the basic musical material (the triadic arrangement noted above) was not ‘of sufficient interest to sustain the development that ensued.’

Some weeks later the symphony was given at the Cheltenham Festival on 6 July 1973 as part of their Berkeley 70th Birthday Celebrations, played by the BBC Symphony Orchestra under John Pritchard. Martin Cooper, who had reviewed the première in 1969, wrote in the Daily Telegraph (7 July 1973) that it was an ‘excellent idea’ to include in the Festival’s opening concert a work that was not one of Berkeley’s recent vocal numbers or an earlier piece with strong French influences. Reiterating some of his earlier opinions, Cooper felt it presented a ‘powerful sense of tension and climax.’ He considered that the orchestra ‘gave a strong well-disciplined performance not helped by the extraordinary resonance of the building.’ It seems that Pritchard had improved on his December 1971 effort.

Select Bibliography (cited or consulted)

Craggs, Stewart R., Lennox Berkeley: A Source Book (Ashgate, Aldershot, 2000)

Dickinson, Peter, The Music of Lennox Berkeley (The Boydell Press, Woodbridge, 1988/2003)

--- (ed.), Lennox Berkeley and Friends: Writings Letters and Interviews (The Boydell Press, Woodbridge, 2012

Scotland, Tony, Lennox and Freda, (Michael Russell, Norwich, 2010)

Files of The Times, Daily Telegraph, The Guardian, Music and Musicians, The Musical Times, Tempo, Radio Times, and Chandos Liner Notes CHAN 10022 etc.

Discography

Berkeley, Lennox: Symphony No. 3 – BBC National Orchestra of Wales/Richard Hickox (includes ‘Sinfonia Concertante’, op. 84, and Michael Berkeley, Oboe Concerto and Secret Garden), Chandos CHAN 10022 (2002).

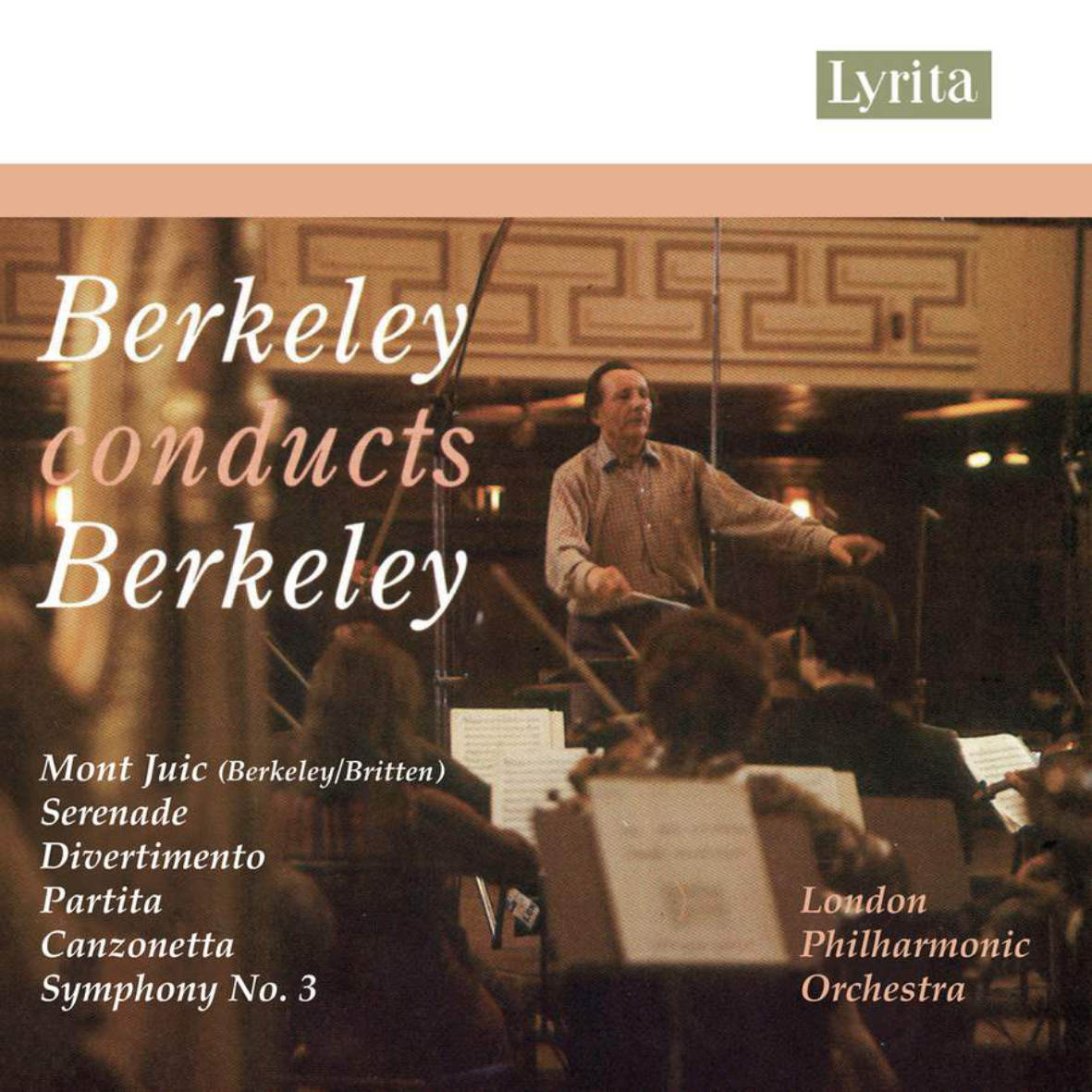

Berkeley, Lennox: Symphony No. 3 – London Philharmonic Orchestra/Lennox Berkeley (includes Mont Juic op. 9, Serenade for Strings op. 12, Divertimento in B flat op. 18, Partita for chamber orchestra op. 66 and ‘Canzonetta’ from the Sinfonia Concertante, Lyrita SRCD.226 1992