Discovering Berkeley’s long-lost ‘Violin Sonata’

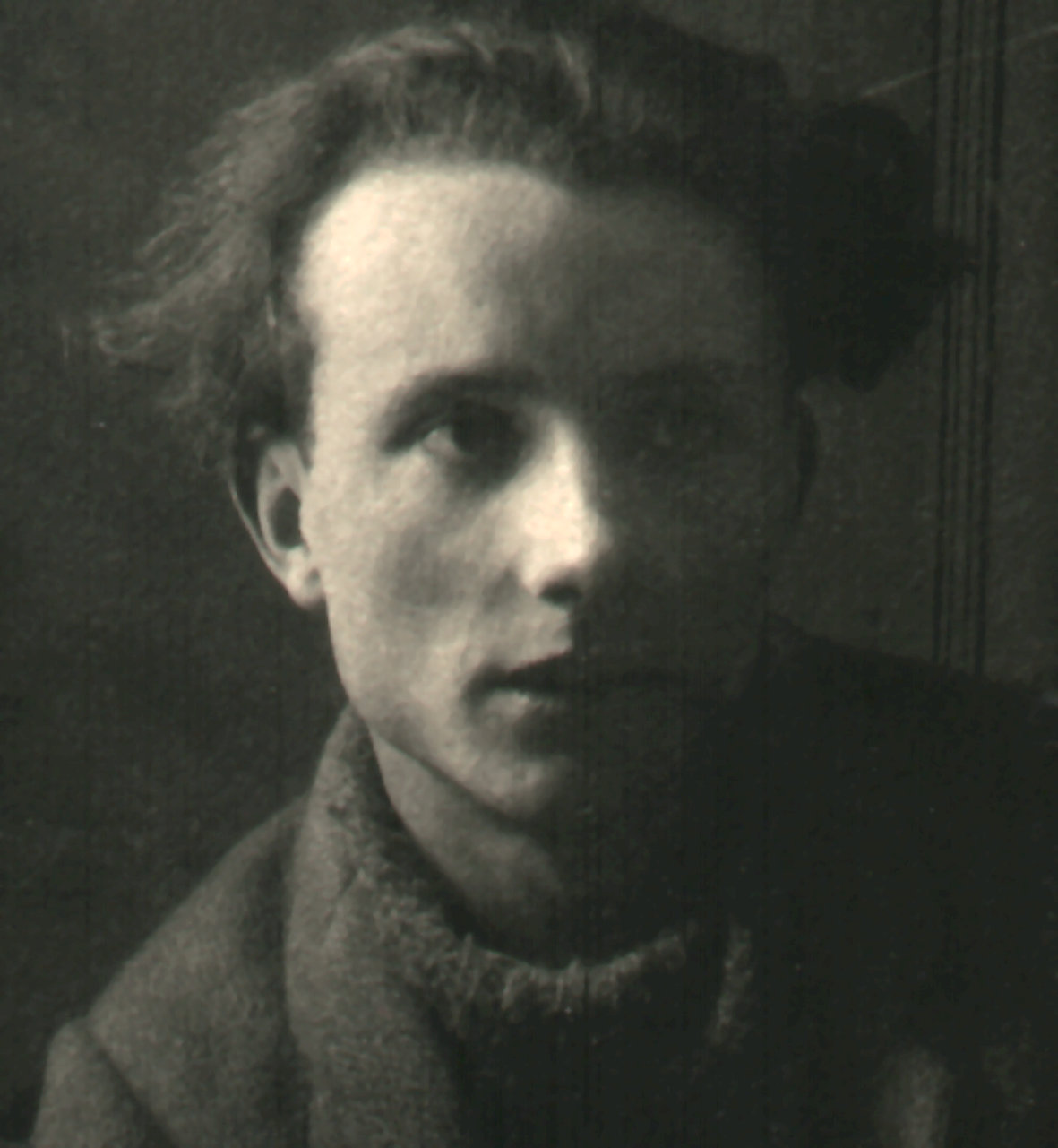

Tony Scotland tells the story of Berkeley’s ‘First Violin Sonata’, composed in 1931 with the advice of Nadia Boulanger, and eventually published by the Lennox Berkeley Society and Chester Music

Lennox Berkeley wrote his Sonata No 1 for Violin and Piano in 1931, and tried it out, privately, in Cannes that summer before sending it to his teacher, the formidable and now legendary Nadia Boulanger, in Paris. In a letter to Boulanger on 22 September 1931, he wrote, in French, ‘… it generally sounds well, but there are some passages where I shall need your advice before making a final copy.’ The new work was given its world première in a concert promoted by the Société musicale indépendante at the École normale de musique (where Boulanger was an instructor) on 4 May 1932; the violinist was to have been Jeanne Isnard-Duval,1 but in the event she seems to have been replaced by Yvonne Astruc, dedicatee of Lili Boulanger’s Cortège.2 A second performance was given in Paris on 28 May.3

Berkeley dedicated the new work, and gave the autograph score, to his doting godmother, Miss Gladys Bryans, an elderly amateur violinist who lived at Painswick in Gloucestershire. In turn she gave it, much later, to another amateur violinist, Jean Kuhn, who passed it on to the violinist Bernard Lewis. In 1978, assuming, first, that the work had never been performed at all, and, second, that it was among those ‘lost’ apprentice works which were thought to have been rejected by the composer, Lewis wrote to Berkeley seeking his permission to give what he believed would be the world première at the Calne Music Festival in Wiltshire the following year.

In reply Berkeley wrote to say he knew he had written two violin sonatas in his student days, ‘but [I] have no very clear memory of them’. He saw no reason why Bernard Lewis shouldn’t play the sonata, if he liked it, but he wondered if he could have a look at it first.4 Just before Christmas 1978 Bernard Lewis personally delivered the manuscript to the Berkeleys at 8 Warwick Avenue, London, but the composer seems to have mistaken his visitor for the postman, and took in the package without a word. The next day, having found a covering letter in the package, he wrote to apologise – and to encourage a second visit so the two could talk about the piece.

Out of respect for one another’s privacy neither man took the next step, and five years passed. Then in 1983 Bernard Lewis caught sight of Lennox Berkeley at a concert in London and reminded him of their brief correspondence, but Berkeley, by then suffering from Alzheimer’s Disease, had no recollection of the earlier encounter. Six years later he died, after which the score joined others in the family’s possession, which were first loaned to, and then last year acquired by, the British Library.

In 2013 the English violinist Edwin Paling, formerly Concertmaster of the Royal Scottish National Orchestra, and the Tasmanian pianist Arabella Teniswood-Harvey, made a much-praised recording of all the Berkeley music for violin and for violin-and-piano, on the Australian label Move Records (MD 3361), using a scan of the Gladys Bryans/Jean Kuhn/Bernard Lewis manuscript score in the British Library, in consultation with the Berkeley scholar Peter Dickinson. Choosing this disc as his Critic’s Choice for 2014 in the Gramophone, Professor Dickinson described it as ‘an amazing rescue operation since Berkeley regularly dismissed his own early music: written in his later twenties, these works again prove him wrong.’

Encouraged by the Australian disc, Chester Music and the Lennox Berkeley Society brought out the first published version of the sonata, based on Edwin Paling’s annotated copy of his BL scan, with notes by Peter Dickinson.5 The previous year Julian Berkeley (the composer’s second son) and I heard the young violinist Emmanuel Bach playing part of the Britten concerto at his prize-winning concert with the Southern Sinfonia in Newbury, and we invited him and the pianist Jenny Stern to give a private performance of the newly-published sonata, for members of the Lennox Berkeley Society in January 2015.

After graduating from Oxford with a double First-Class Honours in Music, Emmanuel decided to take a Masters at the Royal College of Music and is now studying there with Natasha Boyarsky, as an HR Taylor Trust Scholar. Himself a graduate of the R.C.M., Julian was eager that Emmanuel and the College should be offered the chance to give the UK première of the Berkeley sonata. In the hopes of forging a new and fruitful relationship with the College, the President of the Lennox Berkeley Society, Petroc Trelawny, approached the Director, Professor Colin Lawson, and the consequence was a concert in the Recital Hall of the R.C.M. on 19 February.

Entitled Exploring the Archives, it started with the Berkeley sonata and included two pieces by Nadia Boulanger, together with a small display of associated materials from the R.C.M. Library, including its own handwritten copy of the sonata’s violin part,6 augmented by some further Berkeley and Boulanger memorabilia loaned by Julian (Nadia Boulanger’s godson).

The First Violin Sonata is certainly a student work, and, it may be that Lennox Berkeley occasionally disowned it, but it is significant that in 1963, when he was asked how old he was when he wrote his ‘first work of value’, and which work it was, Berkeley replied, without hesitation, ‘Twenty-eight. First violin sonata.’ 7