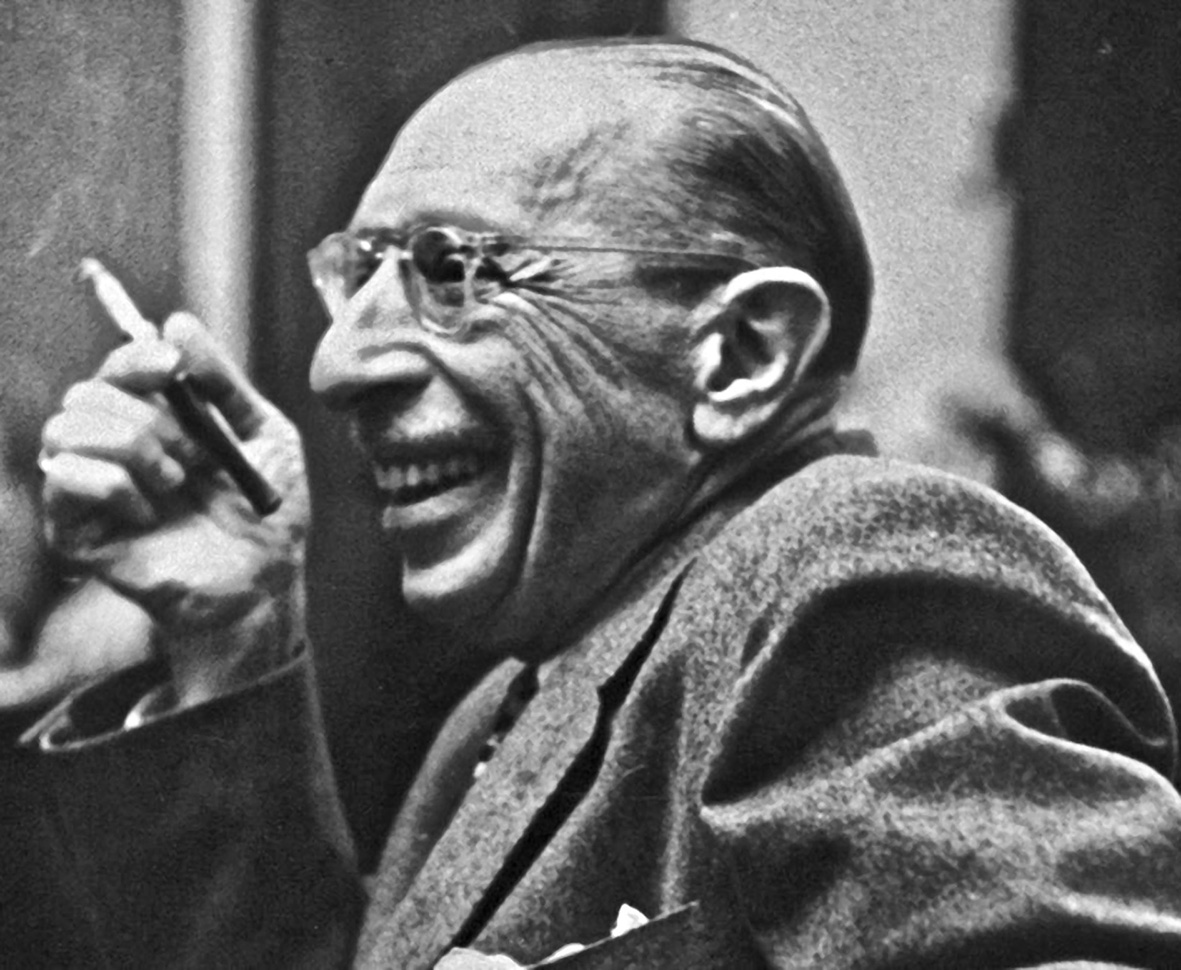

Lennox Berkeley and Stravinsky 1934

Tony Scotland introduces his book about Lennox Berkeley’s journey to Paris with Stravinsky in the Boat Train 1934

When Lennox Berkeley caught the boat train from Victoria to Paris on 30 November 1934, he little expected to share the journey with his musical hero, Igor Stravinsky. Two nights earlier he had attended the British première of Stravinsky’s melodrama Perséphone at the Proms, and, full of ideas, he had hurried back to his own new work, the sacred drama Jonah, over which he had been agonising for some months.

Working on the score through the next day, he missed the royal wedding that gripped the rest of London – the marriage, in Westminster Abbey, of Prince George, Duke of Kent (younger son of the late King George V) and the beautiful Princess Marina of Greece and Denmark. Early on the morning of the 30th he packed for Paris, where he had been living since starting his studies with Nadia Boulanger in 1926, then took a taxi to Victoria for breakfast at the Grosvenor Hotel, with its convenient back door straight onto the concourse of Victoria Station.

He had a ticket for the Golden Arrow Pullman express, which was due to arrive in Paris in time for dinner. At Dover the Southern Railway would transfer him to the luxury steamship Canterbury, and at Calais he would transfer again – to the Arrow’s French counterpart, the celebrated Flèche d’Or express (hauled by a Pacific 231 locomotive) for the final leg to Paris. The English and French operators had perfected the transfers so that the journey took only six hours and forty minutes from Victoria to the Gare du Nord. Berkeley was well used to this journey now that the BBC was beginning to take notice of his work, and London concerts were coming his way.

Settling himself in the Pullman bar with a pot of coffee and some brioches, he pulled the manuscript score of Jonah from his attaché case and set to work again. But just as the train emerged from the Penge Tunnel under Crystal Palace he suddenly caught the familiar whiff of a Caporal bleu and the unmistakable sounds of Russian French – and there the great man was.

The two men had already met in Paris, through Stravinsky’s younger son, Soulima, who was a fellow student of Boulanger and had taken Berkeley to dinner at home in la rue du Faubourg St-Honoré, and through Boulanger herself, who had been helping Stravinsky with the scoring of Perséphone. But they had not planned to meet on the boat train that day. Pleased to see Berkeley again, Stravinsky insisted that he should join his ‘secretary’, Vera Sudeikina, and his collaborator, the violin virtuoso, Samuel Dushkin for bridge and drinks, talk and luncheon in the Wagon Restaurant.

Stravinsky was then fifty-two and at the top of the tree, Berkeley was thirty-one and still on the lowest branches, but they both had much in common. In their different ways they were both musicians’ musicians, moving forward with their compositions, constantly exploring new ideas. Both were currently composing in the neo-classical mode, Berkeley slavishly in Stravinsky’s wake, like so many other young composers in Europe and America, then and later; and both – unlike, say, Britten – composed at the piano, Stravinsky because he needed to feel the vibrations of the strings. Both had links with Diaghilev and were intimate with Ravel, Poulenc and especially Boulanger – a mother figure to whom they remained devoted for the rest of their lives.

Both men were well connected: Stravinsky’s father, Fyodor, a star operatic bass at the Mariinsky Theatre in St. Petersburg (the Chaliapin of his day who created roles for Tchaikovsky and Rimsky-Korsakov), was descended from the noble Polish Catholic family of Sulima-Strawinski, while his mother, as she never forgot, was the daughter of an Imperial State Counsellor in Tsarist Russia; Berkeley was the grandson of the 7th Earl of Berkeley. These things may not have mattered to Berkeley, who knew little about his ancestors anyway, but they mattered very much to Stravinsky, for whom social position, success and money were temptations he had always found it hard to resist.

Both were deeply, if privately, religious – Stravinsky as a wavering Russian Orthodox with a strong attachment to his Church’s superstitions, Berkeley as a devout Roman Catholic convert with a strong attachment to St. Teresa’s mysticism – and both revered their mothers with an almost religious intensity; additionally both were profoundly drawn to their respective Church’s chants, liturgical rituals and icons, and both saw music as a means of praising God.

Both had complicated love lives – the married Stravinsky with women (despite unsubstantiated claims by his protégé and biographer, Robert Craft, that Stravinsky had had early affairs with Rimsky-Korsakov’s son, with Diaghilev, the Belgian composer Maurice Delage and even the immaculate Ravel); Berkeley had always preferred young men (though within twelve years he would find himself happily married, and later the father of three boys).

The big difference between them was that Stravinsky was already one of the great celebrities of the world, a revolutionary genius who had stretched the boundaries of music, and a brilliant self-publicist who consciously encouraged the myth that surrounded him, while the modest but musically ambitious Berkeley was, as his nursery nickname of ‘Coss’ indicated, still an ‘unknown quantity’.

During the time they were together on the Flèche d’Or I have imagined that they talked about Perséphone and Sudeikina’s influence, Jonah, neo-classicism, the purpose and meaning of music, reactionary critics, Mussolini, crayfish and steam engines; the encounter also stirs them to take stock of their complicated emotional lives.

In this new book built on a brief clue in a letter Berkeley wrote from Paris the following day, I have reconstructed the journey according to the few facts, and invented the conversation, using thoughts known to have been expressed by each on other occasions. It came to me during a long illness last year. Fanciful it may be, but I hope it may cast a different light on both composers.