Obituary of Sir John Manduell

Tony Scotland pays tribute to composer John Manduell, pupil of Lennox Berkeley and founding President of the Lennox Berkeley Society

The composer and music administrator Sir John Manduell, who died on 25 October, was not only a leading figure in British music for nearly sixty years, but the Society’s first President and one of Berkeley’s most effective advocates. He was also involved in the setting up of El Sistema in Venezuela, and served on the Boards of the British Council, the Arts Council, the Association of European Conservatoires, European Music Year, Northern Ballet, the European Opera Centre and Covent Garden – and still found time to compose.

Born in Johannesburg, he studied at Jesus College, Cambridge, the University of Strasbourg, and the Royal Academy of Music, where his composition teacher was Lennox Berkeley.

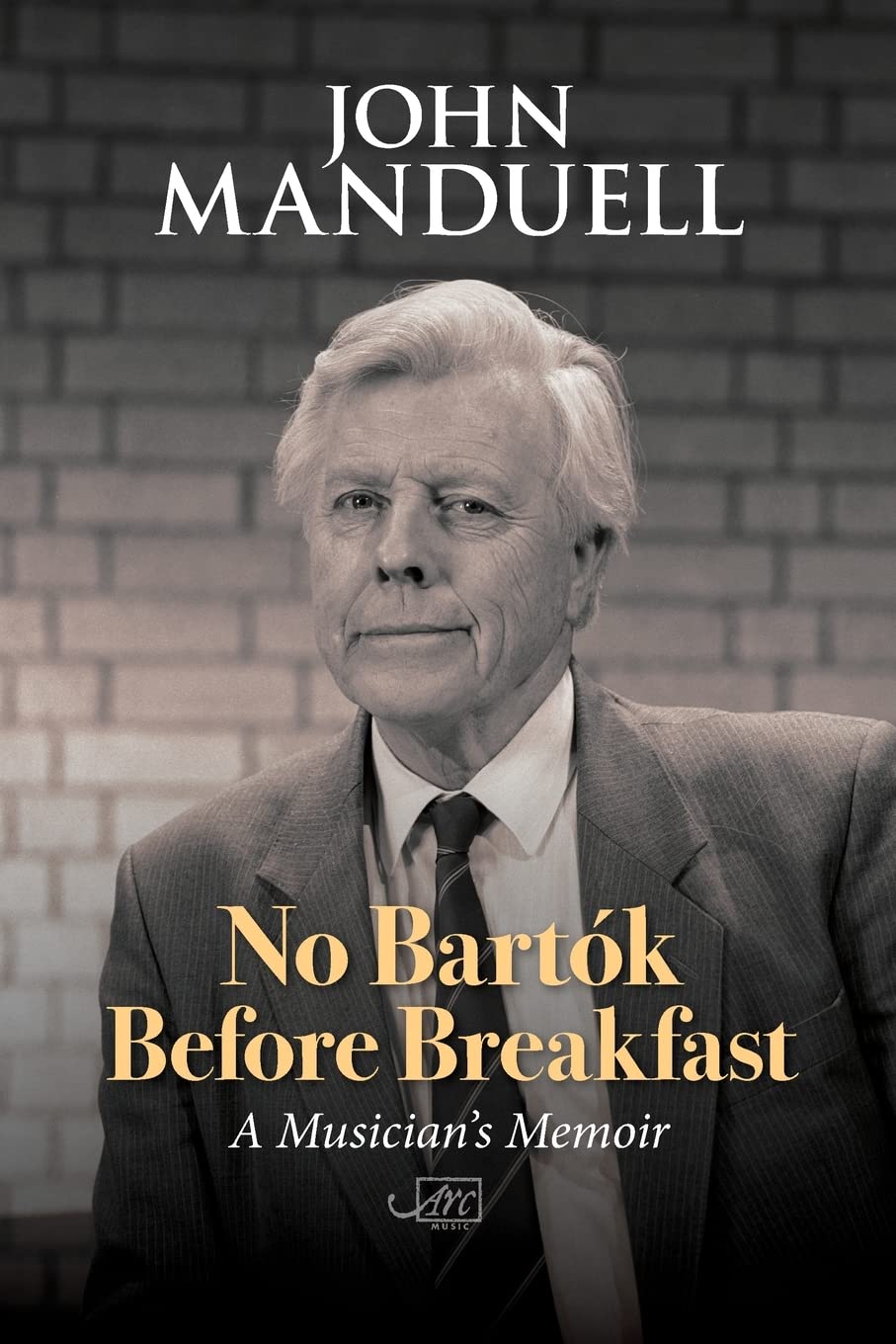

After joining the BBC as a music producer in 1956 John Manduell went on to plan the new Music Programme which replaced the old Third Programme (and would soon become Radio Three). The BBC’s intention was that the new service should be ‘kept firmly in the “middlebrow” range’ – hence an instruction from the Controller of the Home Service, ‘No Bartók before breakfast’ (a telling tag which Manduell borrowed as the title of his book of memoirs.1)

On leaving the Corporation in 1968 he became the first Director of Music at the University of Lancaster and, in 1971, the first Principal of the new Royal Northern College of Music, where he remained until his retirement in 1996.

For a full quarter of a century, from 1969, Sir John was also Programme Director of the Cheltenham Festival, during which time he commissioned no fewer than 250 new works. For the last six of those Cheltenham years, Lennox Berkeley served as President of the Festival, and in 1983 Manduell celebrated his old teacher’s eightieth birthday by inviting fifteen former pupils to write a variation of a minute each on a theme from ‘The Reaper’s Chorus’ in Berkeley’s opera, Ruth. Manduell himself edited the contributions into a cohesive whole and added his own introduction to what he called Bouquet for Lennox.

Throughout those Cheltenham years Berkeley’s music was constantly featured at the festival, whilst Manduell’s own work was more often heard at the Cardiff Festival. And when he retired from Cheltenham, it was Lennox’s son, Michael, who succeeded him.

In a Foreword to No Bartók Before Breakfast, Michael Berkeley described his mentor as ‘a pivotal cog’ in twentieth-century musical life in Britain, and he paid this personal tribute:

John has enabled, eased and cajoled so much that is of value in our musical life with the kind of determination that marks out people who are really going to make things happen. Whether his early life in South Africa informed his ability to aim high as a musical big game hunter I do not know, but what I have personally borne witness to is John’s extraordinary sense of commitment and loyalty to those he believes in (including countless composers and students) and those he counts as friends.

In a letter of condolence to Sir John’s widow (the pianist and teacher, Renna Kellaway), our President, Petroc Trelawny, and Chairman, Adam Pounds, wrote that without Sir John’s support and enthusiasm the Berkeley Society could not have grown into the ‘vigorous, passionate organisation’ that it is today. The letter went on:

From the start he encouraged us to be ambitious and broad-thinking in our efforts to promote the musical legacy of his teacher. Many of the grander projects we took on – our disc of Lennox’s songs, the partnership with the Royal Academy of Music, and last year’s Stabat Mater tour and CD – were a direct result of his determination that we should set ourselves high goals.

In an affectionate memoir of his time as a student of Berkeley, Sir John told readers of the Society’s 2012 Journal that he regarded his teacher at that time as holding ‘a near-divine pre-eminence’. Berkeley was, he wrote, ‘one of this country’s most admired and distinctive composers.’ It would surely have pleased Sir John that Lennox and Freda Berkeley thought just as highly of him, both professionally and personally.