Christopher Daly tribute to Julian Bream

Guitar teacher Christopher Daly on Julian Bream as musician and guitar

The passing of Julian Bream on 14th August last year meant our saying goodbye to a very great musician and performer. He had brought dedication and vitality to his chosen instrument, and made an invaluable contribution to our musical life throughout a half-century. To aspiring guitarists, he was a veritable reference point, and for the future we are very thankful to have recourse to an important legacy of fine recordings, many of which received prestigious awards in their day.

Many years ago, one particular Bream recital left me with an unusual and significant memory. The venue was the church of Gussage All Saints in Dorset, and the programme an excellent one beginning with Frescobaldi and ending with Walton. Included was a transcription of the Sonata No 1 in G Minor BWV 1001 by Bach.1 During the opening ‘Adagio’, there came a passage in which the guitar seemed wholly transcended by the overwhelming beauty and shapeliness of Bach’s melodic line. It took great musicianship to achieve this level of communication. Such was the mastery of this guitarist.

A century ago, it was the destiny of the great Andrés Segovia to bring the solo classical guitar into the world of the modern concert hall. To achieve this, he needed three things in particular: fine musicianship, fabulous technique and, not least, a worthy and persuasive repertoire. He reached right back to the vihuelistas of the sixteenth century,2 and played music from all periods up to his own time. Looking forward, he persuaded composers who were not themselves guitarists to write for the instrument.3 This was a great advance.

Little more than a generation after the Spanish master, Julian Bream began to make his own remarkable contribution to the advance of the classical guitar. Looking to the past, he was, like Segovia, fastidious in his choices from the historic repertoire, and also added transcriptions of his own which he performed and published. These included editions of works by welcome names such as William Lawes, Buxtehude and Cimarosa. Bream’s collaboration with modern composers resulted in new works from Arnold, Berkeley, Britten, Walton and many others. Thus, the expressive possibilities of the instrument were developed and revealed in contemporary compositions of high musical worth.

Julian’s cooperation with Lennox Berkeley resulted in the Sonatina, Op. 52 No 1 of 1957.4 This fine work is thoroughly idiomatic, yet displays the Berkeley elegance throughout its three movements. It is now well established in the guitar’s modern repertoire and is much recorded. It is, though, a work needing a disciplined approach to the composer’s requirements, and very careful attention to time, rhythm and tempo.

A few years later, the guitarist worked with Lennox Berkeley again, this time on a commission from the great Peter Pears. The Songs of the Half-Light Op. 65, for high voice and guitar, consists of five short poems by Walter de la Mare.5 This work was mentioned in the only conversation I ever had with Sir Lennox, in a meeting whose memory I cherish.6 He indicated that ‘it is difficult to put the voice and guitar together’ in these songs. Looking at the score, it is easy to see why, because the guitar writing has so much variety of rhythm and texture as well as demanding harmonic progressions. The five guitar parts alone would make excellent studies. As far as I know the Songs of the Half-Light were not recorded by Pears and Bream.

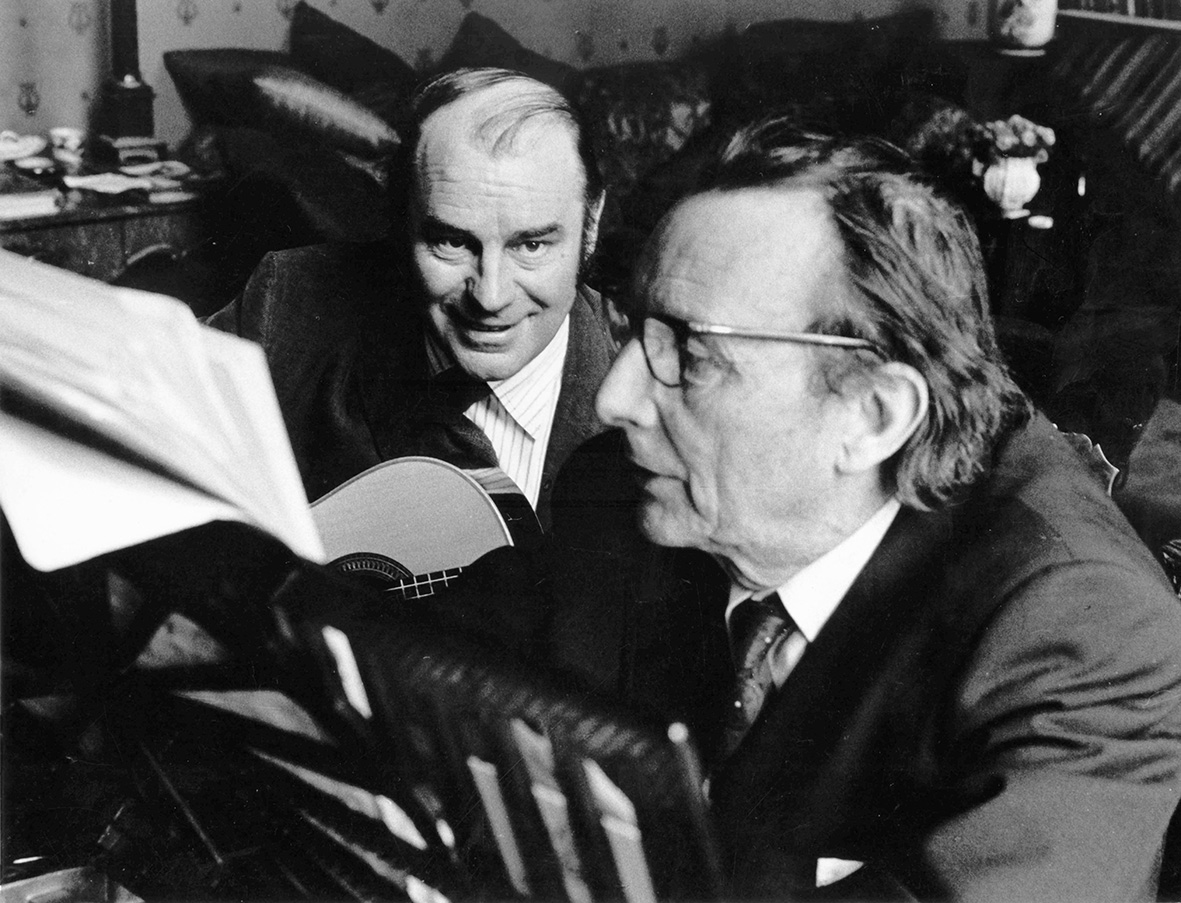

During the exchange referred to above, the composer reminded me that he had written a guitar concerto. This was, of course, the Concerto for Guitar Op. 88, composed for the City of London Festival of 1974. It is a fine addition to the repertoire for guitar and orchestra, and an indication of how successfully Julian and Sir Lennox worked together. The first movement, ‘Andante’, begins with a beautiful duet for horns, suggestive of the main theme, which is then stated by solo flute over guitar accompaniment. Julian expressed his particular admiration for the melody of the second movement, ‘Lento’, another lovely cantabile in five-eight time. The finale, ‘Allegro con brio’ is very lively, always engaging and highly developed for the soloist. Lennox had this to say about working with the guitarist on Op. 88 – ‘I learn a lot about performance with him. He has a wonderful sense of what will come off best, and great determination in finding it’.7

A very different aspect of Julian Bream’s astonishing success was his involvement in the music of Dowland and his contemporaries. 8 He took up the lute which he was to play for solos, songs and consort music, and brought great vitality to these wonderful traditions of the first Elizabethan age. Whether playing the lute or the guitar, Julian found a superb partnership with Peter Pears and proved himself a first-rate accompanist. This is particularly revealed in a recording they made in 1963 of modern songs with guitar, including works by Britten and Walton. The guitar is completely supportive of the singer, yet nuanced and beautifully expressive in its own ways. As Bream said, ‘The guitar has an evocative sound, lending support to the singer. One gives lustre to the other’.9

Away from the concert hall and recording studio, our guitarist liked to play in inspiring rooms which were also able to slightly lift the often subtle tone and dynamics of the instrument. One of these was the Adam library of Kenwood House, Hampstead. During the early 1960s several LP recordings were made there. After his move to the Wiltshire village of Semley a few years later, most of his solo recordings were made in the enclosed chapel of New Wardour Castle near Tisbury, and the last ones at Forde Abbey. Surely one of his smallest concert venues was Semley Parish Church, very near his home, Broad Oak House. For several years the guitarist would hold a little festival there over a summer weekend. Friends such as John Williams, Ossian Ellis, William Bennett and Peggy Ashcroft would join him for these delightful events intended mainly for his neighbours.

These are initial thoughts on the end of an era. The Society can be proud that Julian Bream was its Patron. He was an outstanding musical personality, immensely talented and accomplished. We are grateful for all he gave us. He now rests in peace from his great endeavours.