Selina Hastings on Lennox Berkeley at Oxford in the Brideshead years

Selina Hastings, biographer of Evelyn Waugh, gives a talk at Merton College in 2019, about Berkeley’s years at Oxford in the Roaring Twenties.

Originally, the subject of this talk was to have been Lennox AT Oxford, rather than Lennox AND Oxford; but Lennox the undergraduate, unlike many of his contemporaries, was a very modest, private individual. There are only minimal records of his time at university, his way of life there very different from that of such flamboyant figures as Evelyn Waugh, Brian Howard and Harold Acton, who spent much of their time getting blind drunk and indulging in the most outrageous behaviour. Although, like them, Lennox spent little time on his official studies, his paramount interest was in music, his pleasure in the company of a few like-minded friends.

Lennox was 19 when he first arrived at Merton for the Michaelmas term of 1922. Oxford was already familiar territory. He himself had been born at Sunningwell, a village only a few miles south of the city, the family not long afterwards moving to a cottage on Boar’s Hill, before eventually settling into The Lodge, a handsome house, with a conservatory and spacious garden, on the Woodstock Road. A further connection was provided by Lennox’s Uncle Randal, later the 8th Earl of Berkeley, who lived at Foxcombe Hall, a faux medieval manor house built at the beginning of the century on Boar’s Hill.

Lennox was fortunate in his parents, both of them kind, loving and very musical. His father, Hastings Berkeley, who had been a captain in the Royal Navy, had written a number of books on obscure subjects as well as compiling a large collection of piano rolls, in particular of Beethoven sonatas and keyboard arrangements of concertos, to which Lennox loved to listen. His mother, Aline, who was half German and a devout High Anglican, was also very musical, exceptionally intelligent and with a pretty singing voice. When Lennox was four he attended the Woodside kindergarten on Boar’s Hill, after which his parents sent him to the Dragon School in north Oxford. Situated on the banks of the Cherwell, the Dragon allowed a freedom which was unusual in boys’ school at the time, with no insistence on walking in crocodiles or wearing Eton collars. Every morning Lennox bicycled to school, where he would join his classmates in singing the Dragon’s song:

A weathercock glistens on high And upon it a dragon is seated And the words on that tin Mean ‘Go in and win!’ And the dragon is rarely defeated. For the dragon above Is the dragon we love And so to the Dragon we sing.

When Lennox was 11 he was sent away from home for the first time, to Gresham’s in Norfolk, his arrival in September 1914 only weeks after Britain’s entry into the First World War. Like the Dragon, Gresham’s was notable for its relaxed approach: apart from a rule that all boys’ pockets must be sewn up to prevent masturbation, there was great freedom, with no fagging or beating, no fierce competition in sports and inter-school matches. In the words of one of its old boys, W. H. Auden, such a policy resulted in ‘the high tone that prevailed throughout the school, and in the courteous attitude of the boys towards visitors and strangers’. The final two terms of Lennox’s school career were spent at St George’s, Harpenden, one of the country’s first co-educational establishments, after which he went up to Oxford, in the Michaelmas term of 1922, only weeks after his parents had sold their house on the Woodstock Road and moved to France.

Oxford in the early 1920s was still a city of grey and gold, from its spiked and pinnacled medievalism to the plain ashlar beauty of the 18th century. The ancient colleges with their cloisters, lawns and quadrangles were networked with narrow streets and passages, beyond which lay woods and water meadows, a slow-moving river and the lush pastoral beauty of the Thames valley. Cattle were driven through the streets to market, and at certain times of day nothing was heard except the sound of church bells. But this was the 1920s, and Oxford was also a city of sports cars and motor-bikes, jazz and gramophones, of the Black Bottom and Chili Bom Bom, of Jack Hulbert and Binnie Hale at the New, Mary Pickford, Harold Lloyd and Charlie Chaplin at the Super. Smart young men wore plus-fours and Charvet ties, while the aesthetes defied convention in polo-neck jumpers and Oxford bags. Christian socialists from Manchester and miners’ sons from Cornwall could be found on the same staircase, breathing the same air as the young bloods of the Bullingdon, who hunted, played polo and got spectacularly drunk on incomes of £3000 a year.

For many of the middle and upper classes who were children of Victorian parents and too young to have fought in the war, frivolity was a way of life. As one of Lennox’s contemporaries, Evelyn Waugh, wrote in The Isis magazine, ‘We are all of us young at Oxford… and do not need a psychology text-book to cause us to yearn once more for the nursery floor.’ Just as it was the fashion to pretend to be homosexual (for those for whom pretence was necessary), so for this rebellious youth it was the done thing to behave like children. The universities, and Oxford in particular, were regarded as a kind of deregulated nursery where bread-and-milk was replaced by plovers’ eggs and champagne, and nobody said anything about going to bed early or not answering back. The undergraduates played practical jokes, got themselves up in fancy dress, devised nicknames for each other and even a sort of private language, an Oxford idiolect that converted the Radcliffe Camera into the Radder, St Giles into the Giler, the Martyrs’ Memorial into the Maggers’ Memogger, and the Bodleian into the Bodder. (As an aside, I remember my father, who was up at Oxford at this period, once holding up a copy of the Daily Express with a picture on the front page of the Queen, the Queen Mother and the Prince of Wales. ‘Oh look,’ he said, ‘The Quagger, the Quagger Magger and the Pragger Wagger.’)

In the words of Anthony Powell, a contemporary of Lennox at Oxford, ‘Raucous high spirits were the trademark of a generation that grew up … too young to enter the war, too old to inherit the peace.’ But raucous high spirits and a dissolute way of life held little allure for Lennox, a tall, dark-haired, rather shy young man. For him, part of the attraction of Merton was that it was one of the lesser known colleges, and of great antiquity, both qualities which appealed to his modesty and conservatism. When he arrived there in 1922, Merton was enjoying a reputation for philosophy in general, and idealist views in particular – a reputation earned chiefly by two leading members of the senior common room, the philosopher F. H. Bradley and his disciple Harold Joachim, who was then Wykeham Professor of Logic and, as it happened, a talented amateur violinist. Lennox’s courses were French, Old French and Philology, chosen mainly because he had been fluent in French since childhood and was widely read in French literature, especially in medieval poetry and modern novels; among his favourites in the latter category were Huysmans, Simenon, Julian Green and Gide, although he never cared for Proust, whose characters he found boring: ‘one would surely run a mile’, he said once, ‘rather than actually encounter the Princesse de Guermantes or M. de Charlus’.

But as always for Lennox, his overriding interest was in music; already he knew that ‘composing was his vocation … and for the rest of his time … to the almost complete neglect of his French studies, he devoted himself to music’. During his first term at Merton, due to some major repair work, the organ in the college chapel was closed, so Lennox took to bicycling over to New College, where for a while he had lessons with the resident organist, William Harris. The mild and modest Harris was an expert on Bach, and taught Lennox a great deal about the composer which was to prove invaluable to him in his later career. So inspirational were these sessions that during the Trinity term Lennox decided to take a further step and introduce himself to Henry Ley of Christ Church cathedral, one of the most distinguished organists of the day. Lennox was fascinated by Ley, and was soon taking regular instruction from him, sitting high up on the Willis organ, looking down on the magnificent cathedral below. Lennox was not a natural organist, any more than he was a natural pianist, but that was of small importance: he was learning about music, about Bach, Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven, Schubert and Brahms, from one of the most inspiring teachers of the early 20th century. And fortunately their musical tastes were similar, both adoring Bach while loathing Wagner.

Although reticent by nature, Lennox was a young man of gentle charm and an excellent conversationalist, and he soon made a number of friends both at Merton and at other colleges. Throughout his undergraduate career his closest friend was Vere Pilkington. Vere, sleekly handsome, witty, and high-spirited, was a keen motorist and pilot, as well as an accomplished musician. He was an outstanding keyboard player – he had his own harpsichord in his rooms – and it was he who introduced Lennox to many early composers whose work at that time had been unknown to him. Lennox composed several pieces for Vere to play on his harpsichord, including Mr Pilkington’s Toye, in imitation of Scarlatti, and also two dances for a piano duet which he and Vere played together.

Needless to say, however, most of the undergraduates who were part of Lennox’s social circle were not particularly musical. Although highly intelligent, many of them showed little interest in their studies, dedicating themselves instead to a flamboyant social life. Robert Byron, for instance, who arrived at Merton the term after Lennox, set out in a letter to his mother the dilemmas that faced him at university: ‘The problems of life that confront one here’, he wrote, ‘are 1. How to find time to do any work. 2. How to get to bed before one (a shilling fine imposed every time you enter the college after eleven…) 3. How to get drunk cheaply. 4. How to be rude first.’

As well as Robert Byron and Vere Pilkington, two other friendships that Lennox formed at this time were with fellow Mertonians, Rudolph Messel and William (‘Billy’) Clonmore. Rudolph, elegant and effete, was the son of a wealthy stockbroker, his grandfather the celebrated Punch cartoonist, Linley Sambourne, his cousin to become the famous set designer, Oliver Messel. Rudolph was outstandingly handsome. ‘Lots of people fell in love with him,’ according to Robert Byron. ‘[He] was very precocious and over-sexed and had a tremendous number of affairs’. He was also clever and charming and, unlike Lennox, had a passion for the works of Wagner. Billy Clonmore, son of an Irish earl, had been Robert Byron’s great friend at Eton, described by Byron as surveying the world ‘through half-closed … eyes, utterly impassive, his simian looks only flickering to life with a well-judged sneer or scowl.’ As John Betjeman said of him at the time, he not only ‘looked exactly like the Mad Hatter: he was the Mad Hatter’.

Lennox, Messel and Clonmore were all members of a small Merton dining club, known as the Myrmidon. Founded in 1865, and famously the model for the Junta, the fictional club in Max Beerbohm’s Zuleika Dobson, it had originally been a haunt of the college hearties, but by now the membership had far fewer hearties than aesthetes. The Myrmidons met twice a term, gathering first for sherry in a member’s rooms, then dinner at the Mitre, the Clarendon or the Criterion, before returning to college for dessert. Not much seems to have happened apart from the obligatory drunkenness and some rather curious parlour games, and Lennox remained a member for only a couple of years. Nonetheless through the friends he made at the Myrmidon he was introduced to a much wider circle, including a sophisticated set of Christ Church men.

Among these were David Talbot-Rice, a studious young man and already a keen archaeologist, currently engaged in the unusual pursuit, among Lennox’s friends, of courting a female undergraduate, a beautiful Russian girl whom he was later to marry. Then there was David Ponsonby, a talented pianist and aspiring composer; the very musical Eddy Sackville-West, a frail, elegant figure, who wore a monocle and spoke in a curiously languid tone. And Wystan Auden, who, like Lennox, had also been at Gresham’s, and was such a loner that he was said to live in hermit-like seclusion in college; his jackets were out at the elbows, his nail-bitten fingers yellow with nicotine, he was never without a large pipe, which he smoked insatiably, explaining his habit as ‘insufficient weaning. I must have something to suck.’ Two other familiar figures at the University and friends of Lennox were John Lloyd and John Greenidge, the latter of whom Lennox had known since boyhood. Both Greenidge and Lloyd had graduated before Lennox came up, but both were so deeply attached to university life that they were frequently at Oxford, Greenidge anxious to keep in touch with his friends, while for Lloyd the chief draw was the infamous drinking club, of which he himself as an undergraduate had been a devoted member.

Situated opposite Christ Church, above a bicycle shop in St Aldate’s, the Hypocrites’ Club – motto ‘Water is best’ – had originally existed as a sombre meeting-place for old Rugbeians and Wykehamists with a taste for folk-dancing, shove ha’penny and the Cowley Fathers. More recently, however, it had been taken over by a group of dissolute Etonians, such as Brian Howard, Harold Acton, Robert Byron, and Billy Clonmore, who habitually got wildly and noisily inebriated. One of the most regular members was Evelyn Waugh, who nightly consumed vast quantities of alcohol, usually ending the evening helplessly drunk, and occasionally violent: he was suspended for a time for smashing up some of the Club’s furniture with his walking stick.

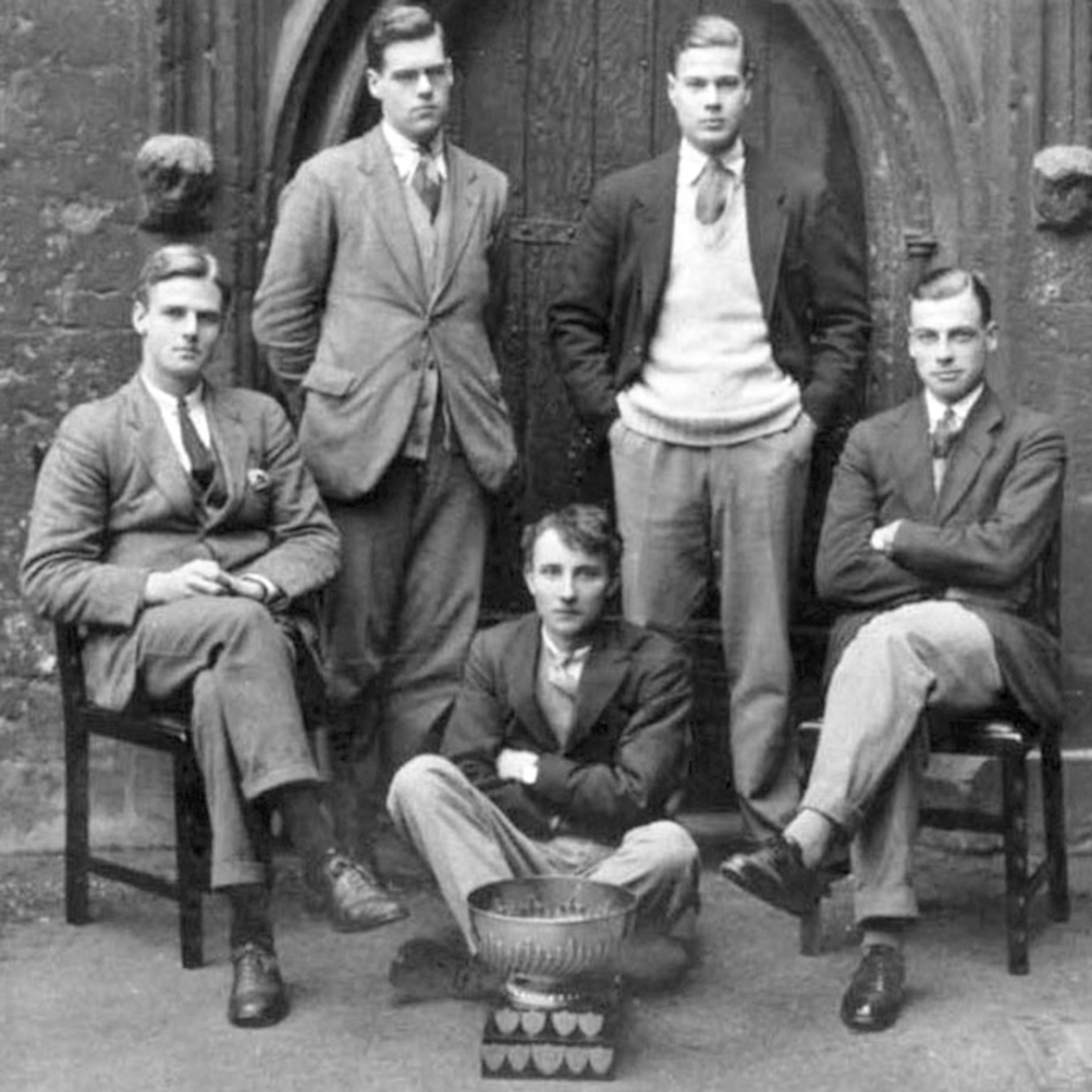

Although friends with a number of the Hypocrites, Lennox, neither athlete nor aesthete, led a far more tranquil life than many of his contemporaries. His slight frame unsuited to both football and cricket, Lennox had never showed much enthusiasm for sport. As John Greenidge’s brother, Terence, wrote on the subject, ‘A brown, sinewy hand may prove a necessary instrument for hitting a six, but pallid, lissom fingers are requisite for playing Chopin exquisitely’. Lennox did for a time take up rowing, in his second term becoming cox for the Merton 2nd VIII. His sense of rhythm was naturally an advantage, and although his exertion of authority was perhaps a little too polite – ‘Would you kindly row a little faster?’, he would ask of his crew – he had a clear, deep voice, and according to another Merton rowing man, ‘a cool assessment of district, ability to ignore all the noise and turmoil from the river bank, steering a straight course throughout.’ In 1923, Lennox coxed the Merton Clinker-built IV to a victory in the Oxford University Boat Club Clinker Fours, winning promotion to the 1st VIII for the following season. As a college cox, Lennox was obliged to attend the riotous Bump suppers that were such a feature of Eights Week, although he was unlikely to have enjoyed the high level of drinking and aggression. The physical discipline and training involved were hard for someone used to neither, and after the second season he gave up rowing for good.

Although well-read and fluent in French, Lennox never showed any great enthusiasm for his studies. In those days it was up to the undergraduate to impose self-discipline, many of the dons remaining somewhat detached, showing little interest in teaching. According to the poet Louis MacNeice, who arrived at Merton in Lennox’s last year, the dons ‘lived in a parlour up a winding stair and caught little facts like flies in webs of generalizations. For recreation they read detective stories. The cigar smoke of the Senior Common Rooms hid them from each other and from the world … they had charm without warmth and knowledge without understanding … Their wit and themselves had been kept too long; the squibs were damp, the cigars were dusty, the champagne was flat.’

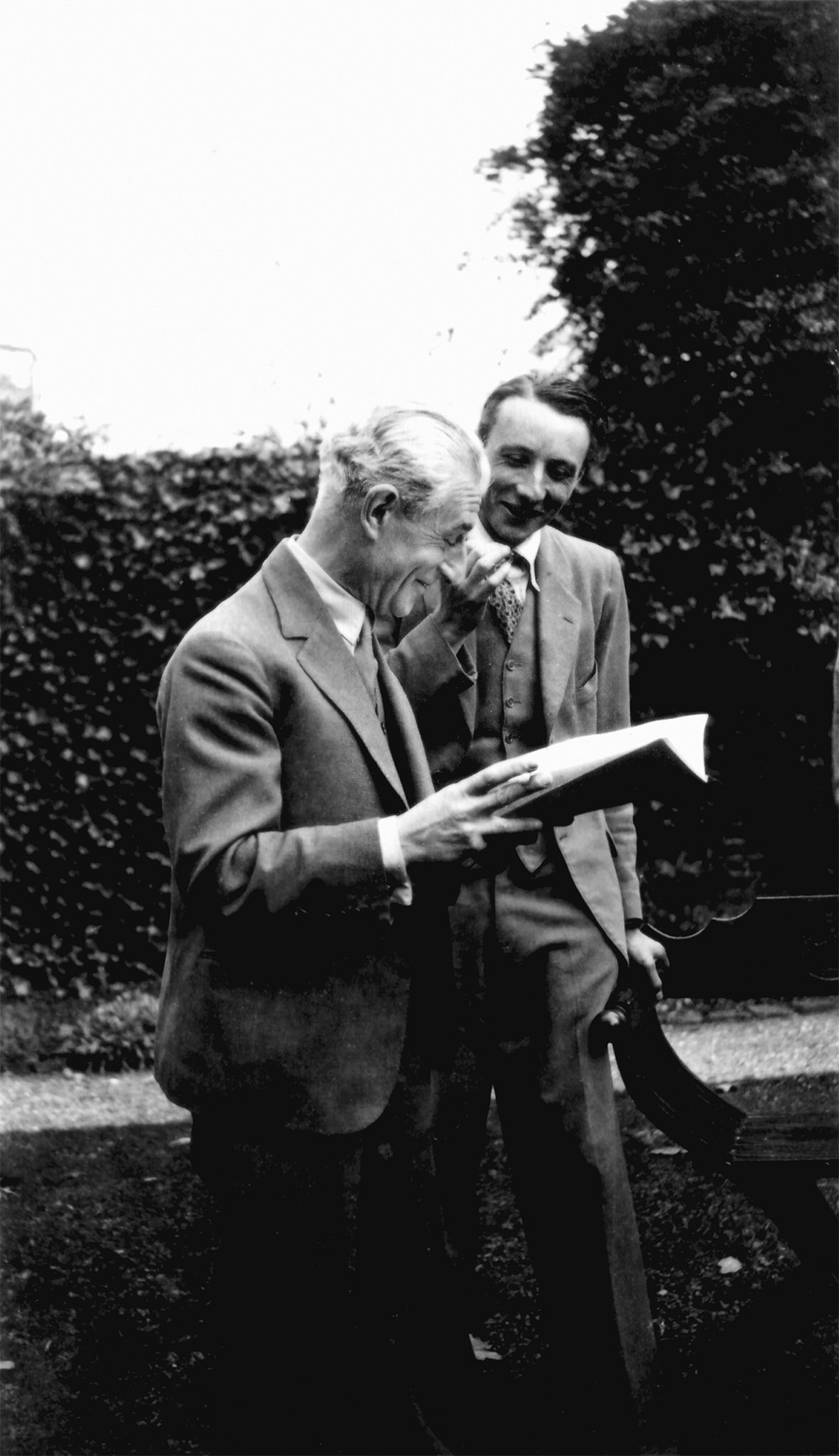

One exception in the Senior Common Room at Merton was the Oxford Professor of Poetry, H.W. Garrod. Lennox, always an avid reader, was keen to set some of his favourite poetry to music, and anxious for guidance he went for advice to Prof. Garrod, quickly becoming part of Garrod’s charmed circle. Unlike most of his fellow dons, Garrod seemed at ease in almost any kind of company, as aware of what was happening in the world outside as within the precincts of the university. Although one of his pupils at the time, the writer, Stephen Potter, described Garrod as an ‘evil old oyster’, he was generally regarded as the presiding genius, most of his pupils feeling for him nothing but admiration and affection. Garrod was a true eccentric, plump, bespectacled, cigar always in hand, his beloved terrier at his feet. Extremely clever, he was also curiously absent-minded. ‘Do you like your tea hot or cold?’ he would ask in his high quavering voice. Garrod loved the company of young men, and quickly took to Lennox, with his large dark eyes, floppy hair and slender figure, a charming and appreciative acolyte. Perhaps unsurprisingly, it was Lennox whom Prof. Garrod suggested accompany him to Sicily for the New Year’s holiday in 1925.

It was almost certainly through Garrod that Lennox discovered the texts by Ronsard, du Bellay and Charles d’Orleans, which he set to music, and were subsequently performed at the Oxford University Musical Club and Union. Later, in his final term, Lennox chose works of a rather more modern period, a couple of poems by Wystan Auden, to be sung by the poet Cecil Day Lewis. It was Auden himself who had suggested to Lennox that Day Lewis should perform; an enthusiastic amateur pianist, Auden had a piano in his rooms at Christ Church, and would play for hours at a time, thumping his way through a series of Bach preludes, a cigarette hanging out of the side of his mouth, scattering ash all over the keyboard. His playing, according to Day Lewis, was ‘loud, confident, but wonderfully inaccurate.’ Unfortunately, the performance, according to Cecil himself, turned out to be ‘a bit of a disaster’, as he limped through the first poem and stalled irretrievably in the second, the reaction from the audience ‘a sustained outburst of silence.’

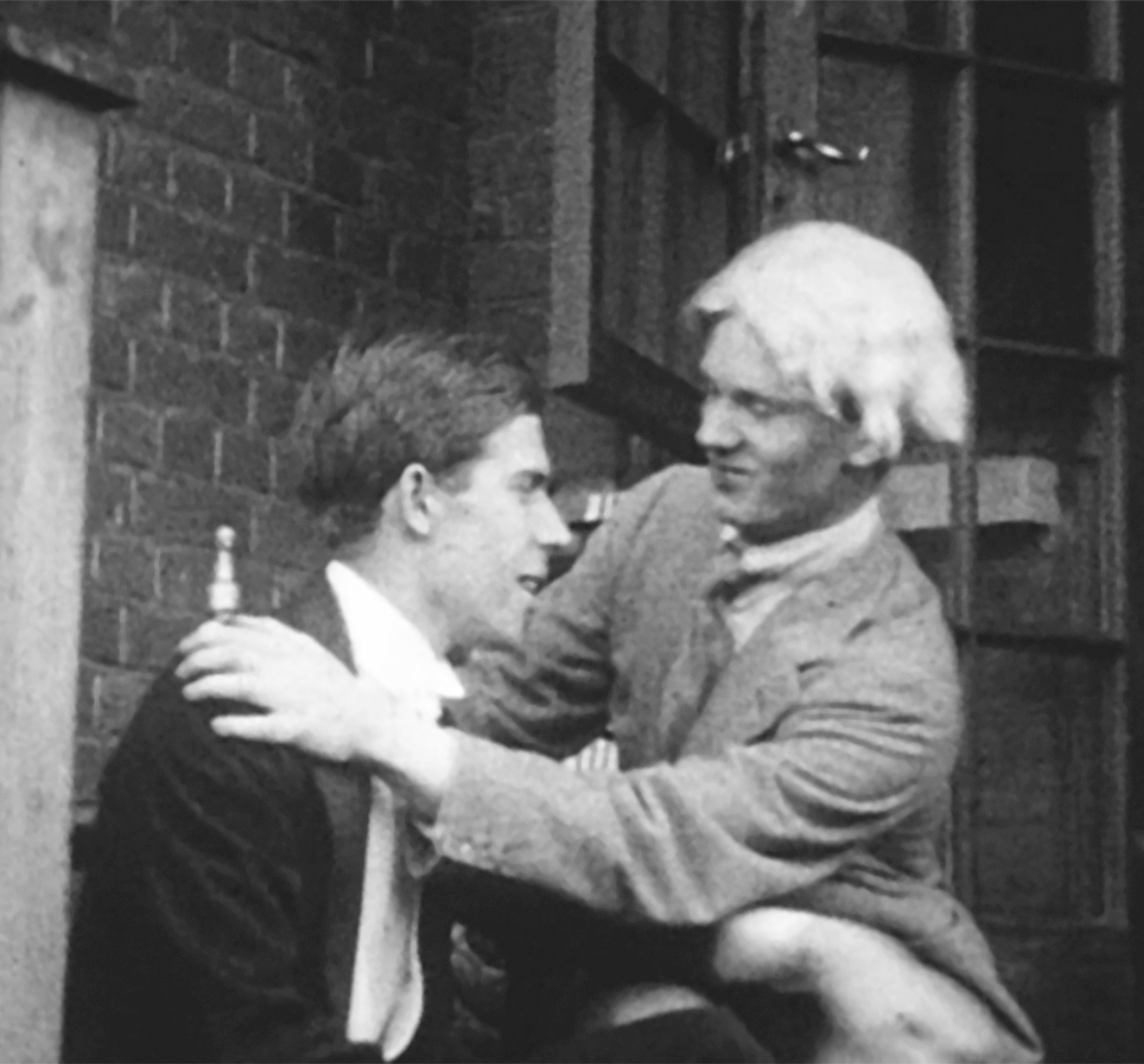

During the Michaelmas term of his second year, in November, 1925, Lennox became involved in the making of a film, for which he had agreed to compose the music. The Scarlet Woman, an Ecclesiastical Melodrama was a typically exuberant undergraduate rag. The comic plot, written by Evelyn Waugh, revolved around an imaginary attempt by Waugh’s old enemy, the Dean of Balliol, to restore Catholicism to contemporary England by exploiting the bisexuality of the Prince of Wales. John Greenidge’s brother, Terence, directed it, the filming taking place in Oxford, on Hampstead Heath, and in the garden of Waugh’s family house in Golders Green. Evelyn in a tousled white wig took the part of Sligger, the dastardly Dean, John Sutro was the crafty Cardinal Montefiasco, Evelyn’s brother Alec Waugh, the cardinal’s drunken mother, and John Greenidge the Prince of Wales, who makes homosexual advances to the Pope. The first showing, at the Oxford University Dramatic Society, with Lennox in charge of the musical accompaniment, was such a success that a request for a second performance was received from the Society of Jesus at Campion Hall. Father Martindale, the Master, was so amused by it that John Greenidge took it upon himself to insert a subtitle, ‘Nihil Obstat … – C. C. Martindale SJ.’

The inter-war period, the 1920s and ’30s, saw one of the most active periods of Catholic conversion in England. This had begun with the restoration of the hierarchy in 1850; the veering towards Rome among Anglicans, both lay and clergy, instigated by the Oxford Movement; the pervasive influence of Cardinal Newman; the continuing mass immigrations from Ireland; and the traumatising effects of the First World War. By the 1930s there were some 12,000 converts a year in England alone; among Lennox’s Oxford generation, as well as Lennox himself, were Christopher Hollis, Graham Greene, Billy Clonmore, Robert Speaight, Harold Acton and Evelyn Waugh. Many, like Waugh, had been brought up Anglican, experienced a period of calf piety in childhood, then turned sceptical agnostic at university. As Mgr Arthur Barnes, the University’s late Catholic Chaplain, used to say, ‘all young men give up religion at 18 to return to it at 23’. Inevitably, there was considerable anti-Catholic feeling in response to this wave of conversion, referred to by the Protestant opposition as ‘embracing the Scarlet Woman’. The hymn-writer John Moultrie called on the Church of England to resist the influence of Rome:

God give her wavering clergy back that honest heart and true, Which once was theirs, ere Popish fraud its spells around them threw; Nor let them barter wife and child, bright hearth and happy home, For the drunken bliss of the strumpet-kiss of the Jezebel of Rome.

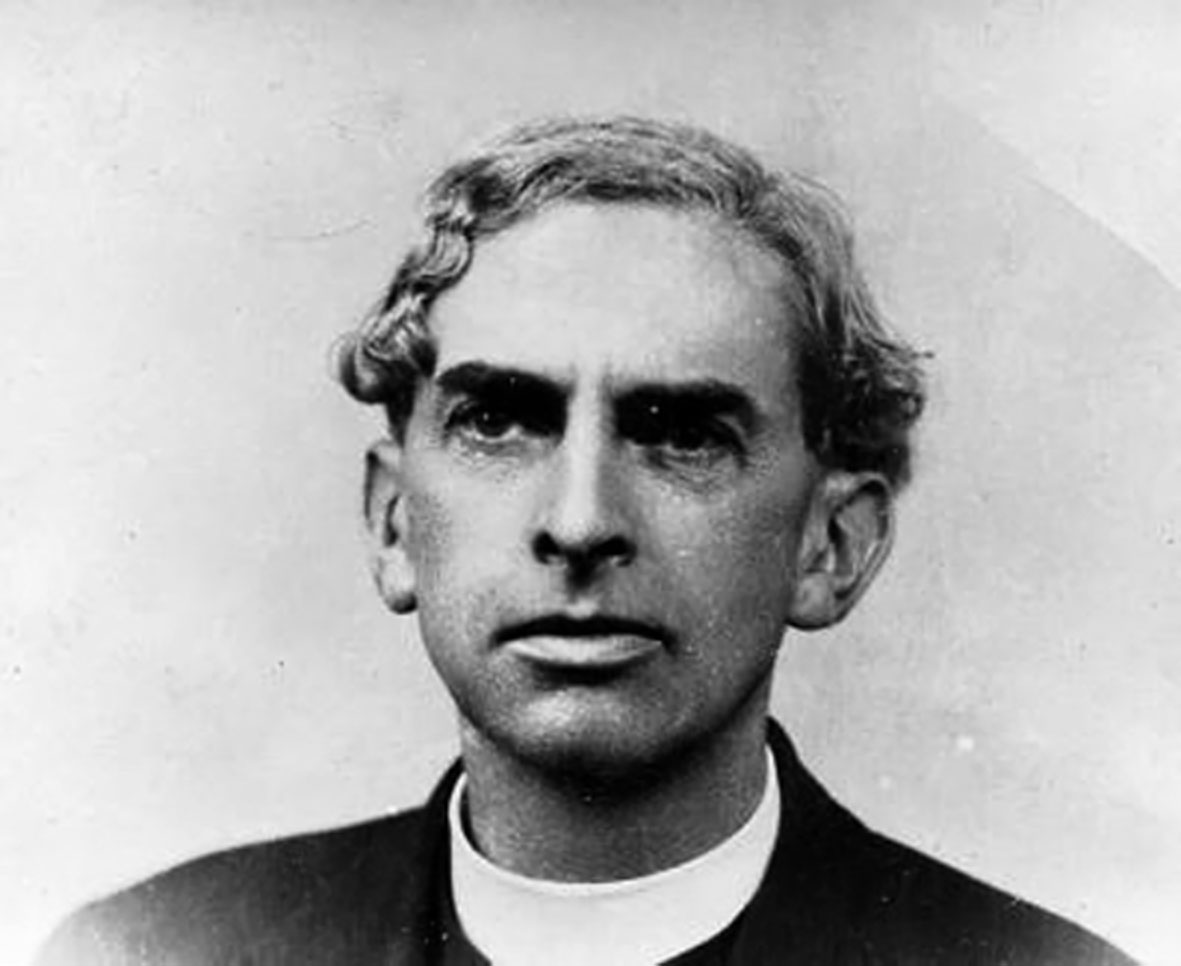

For Lennox, who was to convert to Catholicism in 1928, the later most significant influence on his religious life was to be the writing of Mgr Ronald Knox, the succeeding Catholic Chaplain, who arrived in Oxford in 1926 just as Lennox was on the point of going down. During his time at university, however, one of the most influential presences was the Jesuit, Father Martin D’Arcy. According to Louis MacNeice, D’Arcy alone among the Oxford dons ‘seemed to me to have the glamour that medieval students looked for in their masters. Intellect incarnate in a beautiful head, wavy grey hair and delicate features; a hawk’s eyes.’ D’Arcy spent much of his working life at the English Jesuit house, Campion Hall, where he taught Moral Philosophy. As a priest he was well known in more elevated Catholic circles for his strong logical mind, his eloquence and his success in bringing into the Church numbers of prominent converts. He regarded the modern age with distaste, looking back with nostalgia to a romantic and dignified past as represented by the great houses and ancient lineage of the old Catholic nobility.

Shortly before Lennox was to sit his finals, in June 1926, the General Strike broke out, lasting from 3rd to 12th May. The government responded by immediately calling on the army and on university students to help keep food supplies and public transport running. Crowds of undergraduates flocked to the major cities to help unload ships, escort food lorries and act as Special Constables, with 83 students at New College alone responding to the emergency. Despite this cataclysmic disruption, the examinations were not delayed, which may, or may not, have influenced the results of that year’s finalists: Lennox ended up with an undistinguished Fourth, as did Harold Acton; Evelyn Waugh was awarded a Third, while Brian Howard went down with no degree at all. But then as Stephen Potter, another Mertonian of that period, remarked, ‘Degrees were less important then … It was even rather magnificent to go down without bothering to take your degree. Oxford was, after all, a mainly social institution.’