The Libretti of Opera

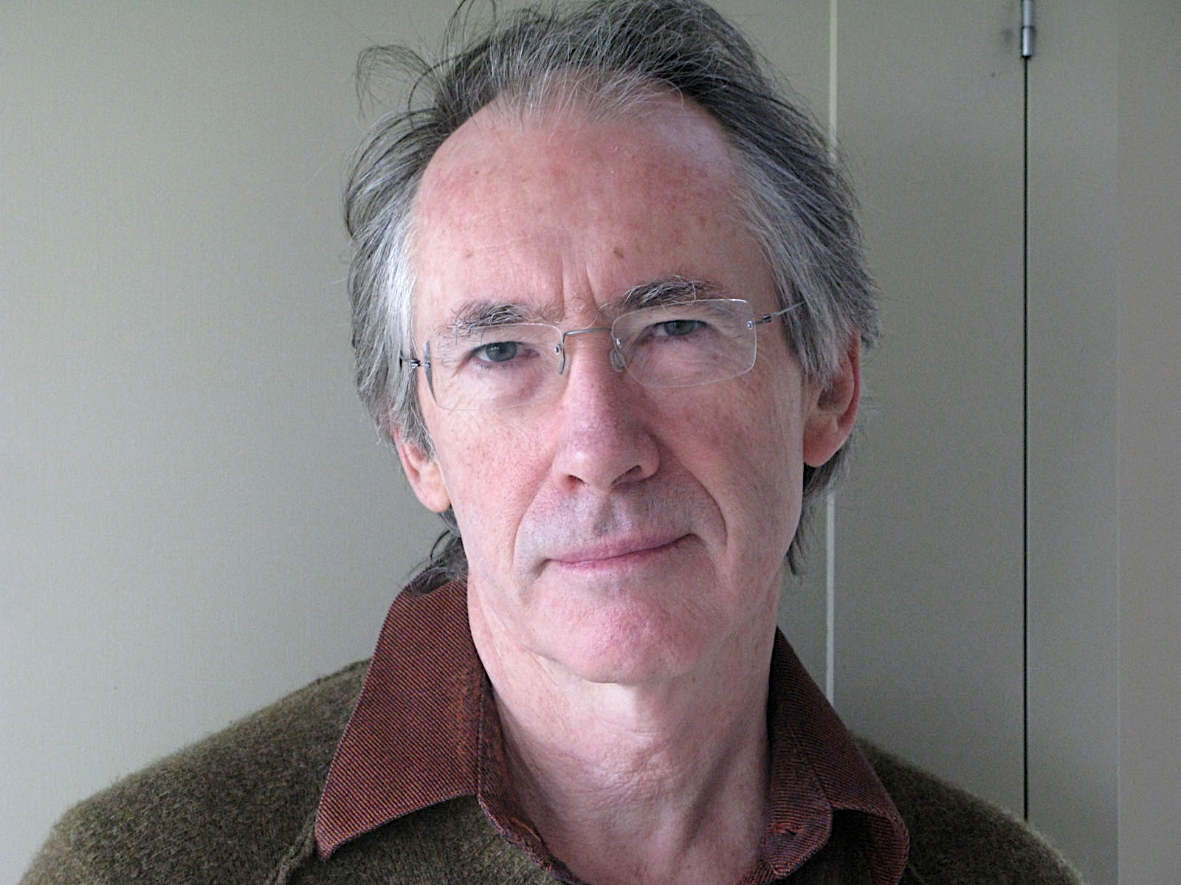

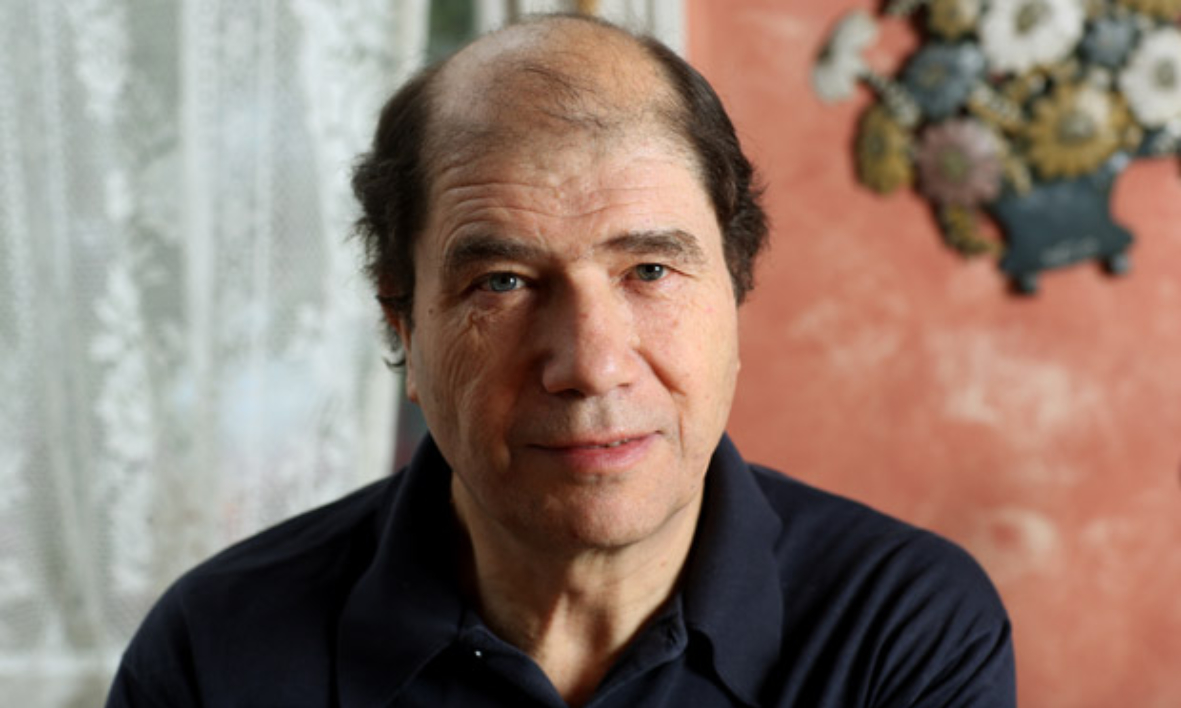

Novelists Ian McEwan and Philip Hensher, opera director Daisy Evans and composer Michael Berkeley talk to BBC Radio 3 presenter Petroc Trelawny about opera libretti

The speakers began by considering how rarely operas are set in the time in which they were written. Philip Hensher made a case for Berg’s Lulu, but Petroc Trelawny noted that while Britten had never set an opera in real time, his friend Lennox Berkeley had set his one-act comedy A Dinner Engagement in the 1950s, the decade when the piece was written. Petroc pointed out that Hensher’s libretto for Thomas Adès’s Powder Her Face, with scenes spanning 1930-1990, and Ian McEwan’s librettto for Michael Berkeley’s For You, a study of sexual obsession set in current times, were among the few other operas which broke the mould.

Ian McEwan talked about Charles, the hero of For You, a successful composer, conductor and compulsive womaniser, in a fever of anxiety over the imminent première of a new work, and obsessed by the thought that his creative powers are failing. It was, he agreed, a tale of now. This raised all sorts of issues about the use of modern language in opera, especially when performed in the vernacular. Ian said he had been determined that the audience should catch every word, and, at the first performance at Music Theatre Wales in 2008, he had fought a small battle with his old friend Michael Berkeley over subtitles: Ian had won, and the show was performed with titles.

Outlining the plot of A Dinner Engagement, with its dated class distinction and social aspiration, Daisy Evans said that she had turned to the medium of cartoon to enhance some of the period aspects of the opera, while offering a view of the work through a brightly-coloured looking glass.

Michael spoke about the librettist of both A Dinner Engagement and The Bear, the poet and Oscar-winning screenwriter Paul Dehn, who had been a friend of his parents and regular visitor to their house in Little Venice. Indeed the burning of an hors-d’oeuvre, which lies at the centre of A Dinner Engagement, was based on a real incident at a dinner party at the Berkeleys’. Best known for his screenplays for Goldfinger, The Spy Who Came in from the Cold, the Planet of the Apes sequels and Murder on the Orient Express, Dehn really understood music and story-telling; his partner, the composer James Bernard, was particularly associated with horror films, having scored such classics as The Curse of Frankenstein and Dracula.

Michael also spoke of the friendship between William Walton and his father, about which he wrote in the 2015 Journal. And he and Ian talked about the way they worked together on For You. Petroc wondered if they would collaborate again – perhaps on Ian’s family saga novel Atonement, which was shortlisted for the 2001 Booker Prize and adapted as a film. They kept talking about it, Ian said – but that was the problem: talking rather than doing.

Philip Hensher said that Powder Her Face had been commissioned by Almeida Opera. Given that no Almeida opera had ever been revived, he and Thomas Adès felt freed from the constraints of traditional opera and had decided to write whatever they wanted. Philip admitted to having done minimal historical research about the period in which Powder was set. After its initial triumph, he and Ades were asked by English National Opera to write another full-scale opera. ‘We will give you someone to work with, so you get the logistics right’, he was bluntly told – so they decided not to accept.

Philip thought it was odd that he was often described as a librettist, even though he has written only one opera – and ten novels. Librettists, he said, were treated very badly. When the Royal Opera House staged Powder Her Face, they had invited the composer to attend, but not the librettist. In the event Hensher had to threaten to withdraw his text before the house finally found him a pair of seats. ‘We are the corporals in the process,’ McEwan said, ‘the composers are the generals. But that is as it should be – it’s the music people remember’.

Afterwards Petroc Trelawny, as Chairman of the Berkeley Society, thanked the speakers for their contributions; the Academy – and, in particular, the Principal, Jonathan Freeman Attwood, and the Director of Artistic Planning, Nicola Mutton – for staging the two operas; and (through their representative, Mr Kenji Fujiwara), Mr Noriyuki Ida and his wife for their generous support of the Berkeley events at the Academy, in memory of their daughter, the pianist Kumiko Ida, who died suddenly in 2007.