Paul’s Dehn’s life in music, poetry, films and wartime spying

Tony Scotland tells the story of Berkeley’s librettist Paul Dehn

The librettist of Berkeley’s operatic double bill (as well as the creator of the MRS RAVOON verses so warmly recalled by John Julius Norwich on pages 16-18), Paul Dehn was also a film critic, broadcaster, novelist, playwright, Oscar-winning screenwriter – remembered for Goldfinger and three of the Planet of the Apes films – and an MI6 spymaster who led cloak-and-dagger operations during the war.

Born in Manchester in 1912, to a German-Jewish family engaged in the cotton trade, Dehn was educated at Shrewsbury School and Brasenose College, Oxford. While at university he edited the undergraduate paper, Cherwell, and wrote an unpublished novel and two unstaged plays. Encouraged by his godfather, the great drama critic James Agate, he decided to become a critic himself. Enrolling as an apprentice reporter on the Stockport Advertiser, he gradually worked his way up to become film critic of the Sunday Referee in 1936.

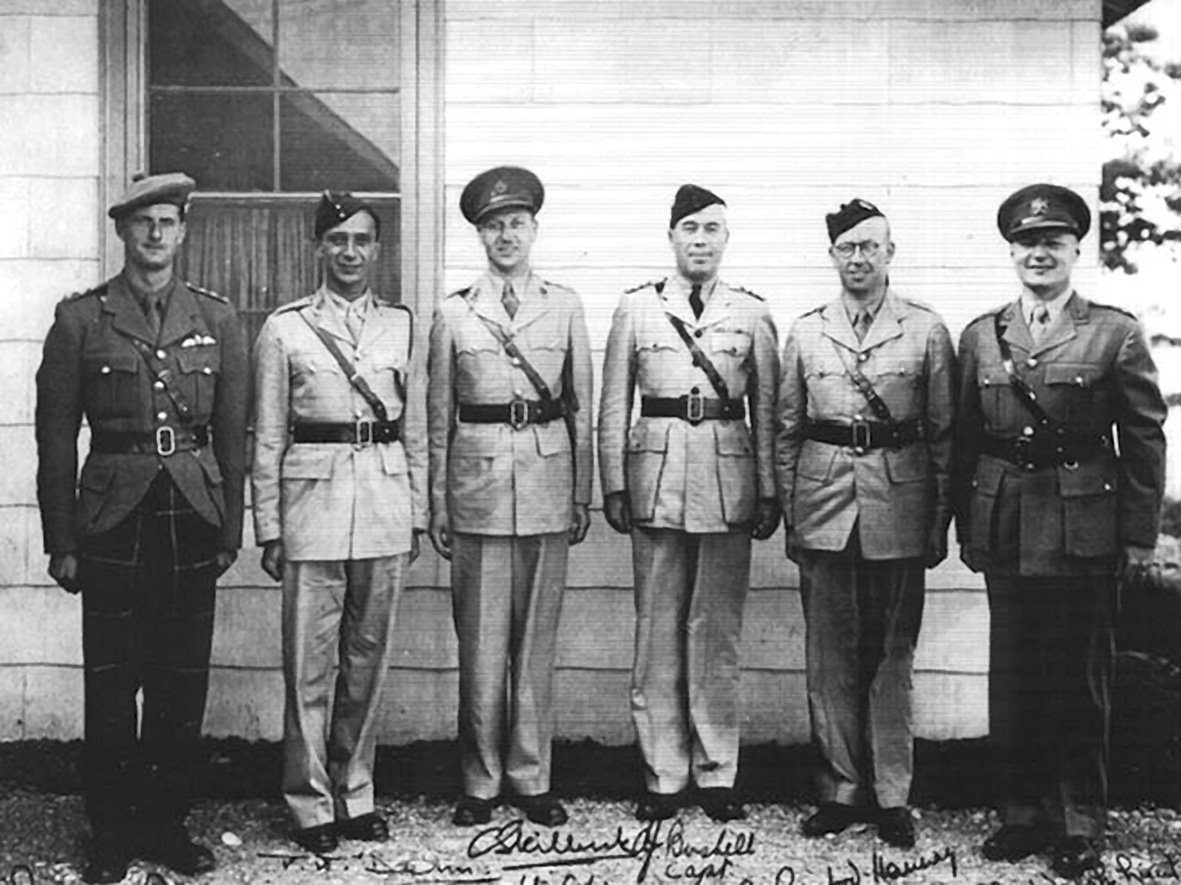

When war broke out he joined the army and was seconded to the Special Operations Executive which had been set up to conduct espionage, sabotage and reconnaissance in occupied Europe and to assist local resistance movements. For most of the war he was based at Camp X in Canada, the secret training school on the shores of Lake Ontario, where he instructed Allied agents how to operate behind enemy lines. With him at The Farm, as it was known locally, were Ian Fleming, later creator of James Bond, the children’s writer Roald Dahl, and the actor Christopher Lee (who was to find fame as Count Dracula). Dehn co-wrote the S.O.E.’s spy-training manual, and drilled spies in the dark arts of black warfare. ‘I was an instructor to a band of thugs called the S.O.E.,’ he recalled years later (in what may be his only surviving interview), ‘and I instructed them in various things on darkened estates, so I got a pretty good view of what counter-espionage was like.’

It was said that every one of the five hundred soldiers who graduated from Camp X could kill a man with his bare hands in fifteen seconds. In an interview accompanying the DVD of the thriller The Spy Who Came in from the Cold (adapted for the screen by Paul Dehn in 1965), the writer John le Carré revealed that Dehn had been a professional assassin. ‘It was a gruesome fact’, he said, that Dehn had had ‘pretty startling experience of the spook world’, but he was ‘a very gentle guy, lovely to work with’.

Promoted to the rank of Major, Dehn was Political Welfare Officer in the SOE from 1942 to 1944, during which time, impatient with teaching, he went on secret missions to France and Norway, took lives and risked his own.

It was in 1944 while working with MI6 at Bletchley Park that Dehn met his life-long friend, collaborator and partner, the composer James Bernard, who was then in RAF Military Intelligence working on the Enigma code-breaking machine with Alan Turing.

After the war James Bernard – on Benjamin Britten’s recommendation – went to study composition with Herbert Howells at the Royal College of Music, and Dehn resumed his versatile writing career, as a poet, playwright, sketch-writer, contributor to the radio programme, The Critics, and film reviewer for, successively, the Sunday Chronicle, the News Chronicle and the Daily Herald. But, according to his own account, he found it so difficult ‘allocating praise and blame justly in a composite work of art like a film’ that he started writing film scripts of his own, in the hope that this would make him a better critic.

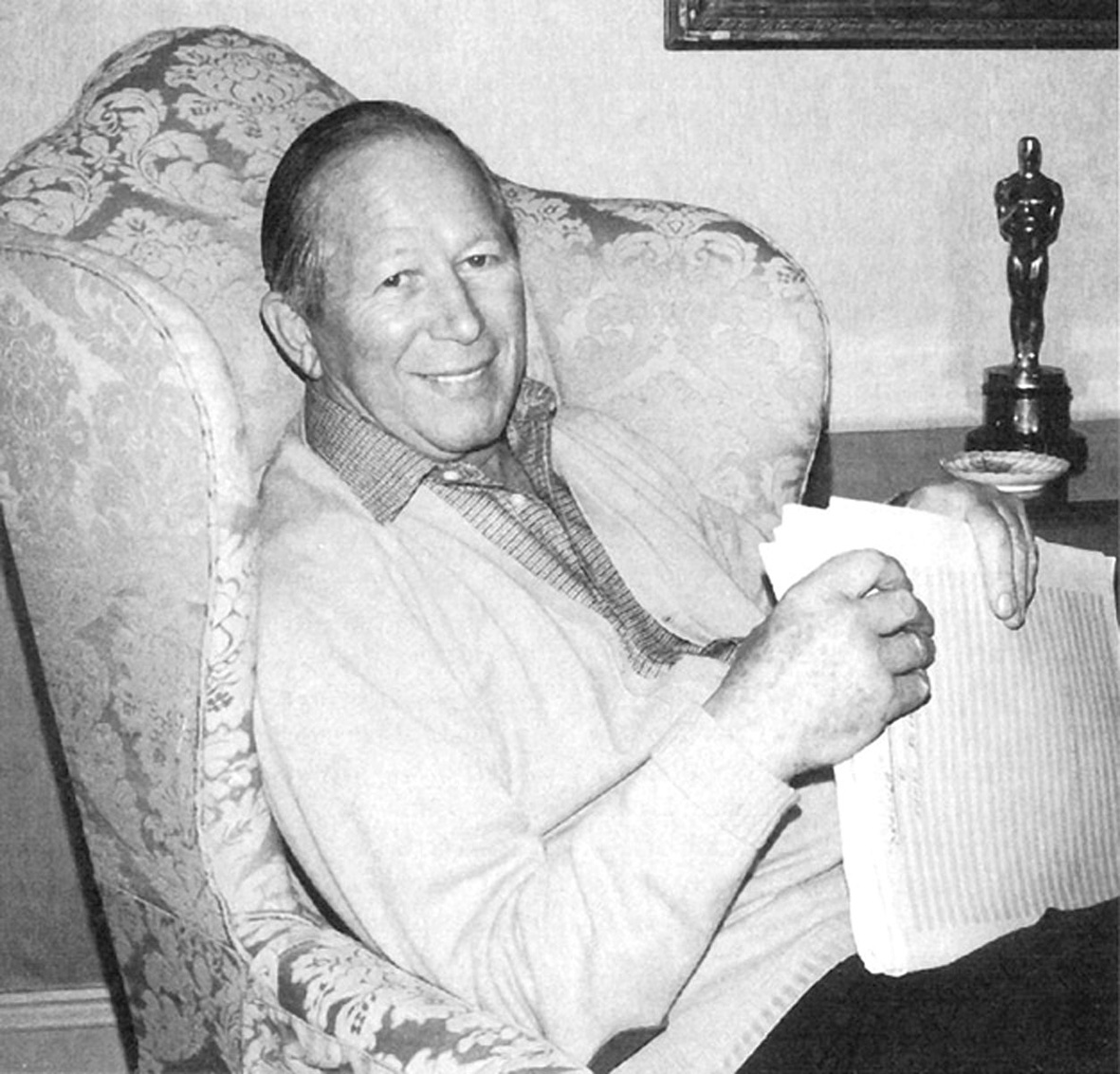

His first foray into films was a collaboration with James Bernard in 1950: a Cold War thriller for the Boulting brothers called Seven Days to Noon, which won them an Academy Award for Best Motion Picture Story. The plot tells of an English scientist who has a religious conversion and steals an atomic bomb, which he threatens to detonate unless the British Government promises to end atomic research within a week. It was a theme that haunted Dehn for the rest of his life, and would later take a darkly comic form in a miscellany of familiar verse rewritten from an anti-nuclear perspective, with ghoulish illustrations by the American artist Edward Gorey. Here is one of Dehn’s disturbing verses:

‘Mary, Mary, quite contrary, Say how the bomb test went.’ ‘I’ll let you know in a week or so, When I’ve had my Happy Event.’ 1

In 1955 Paul Dehn wrote the script for Anthony Asquith’s film about Glyndebourne Opera, On Such a Night, and three years later Asquith invited him to write the screenplay for his wartime drama, Orders to Kill, which won a BAFTA Award for Best Screenplay.2 In 1963 he decided to take the plunge and become a full-time screenwriter. Within a year he had won his first big break with Goldfinger, regarded by many as the definitive James Bond film. This led to a string of successes, including The Spy Who Came in from the Cold (1965), The Deadly Affair (1967), Zeffirelli’s The Taming of the Shrew the same year, three Planet of the Apes films between 1970 and 1972, and the all-star Murder on the Orient Express (1974), which won him an Oscar nomination for Best Adapted Screenplay.

Meanwhile James Bernard (a direct descendant of the composer Thomas Arne) was making his mark as a film composer, with X the Unknown, The Quatermass Xperiment, and all the Hammer horror films which followed – from The Curse of Frankenstein (1957) to Frankenstein and the Monster from Hell (1974).

It was James Bernard who brought Dehn and Berkeley together in the late 1940s. While still a student at the RCM, but already sharing a house with Paul Dehn, off the King’s Road, Bernard was invited to tea with the Berkeleys in Warwick Avenue. Speaking on Michael Berkeley’s Radio Three programme, Private Passions, years later, he recalled, ‘We became great friends and they soon invited me and Paul – and the cups of tea turned into the most wonderful gourmetic dinners, which we used to exchange in each other’s houses. One of my most vivid memories of Lennox would be at the beginning of a dinner party when he’d be mixing the drinks. He loved mixing dry Martini cocktails – and his Martinis were the real thing: a great deal of gin or vodka with just the merest hint of vermouth; and I can see him mixing them now, with a kind of sparkle about him and a boyish zest and happiness.’

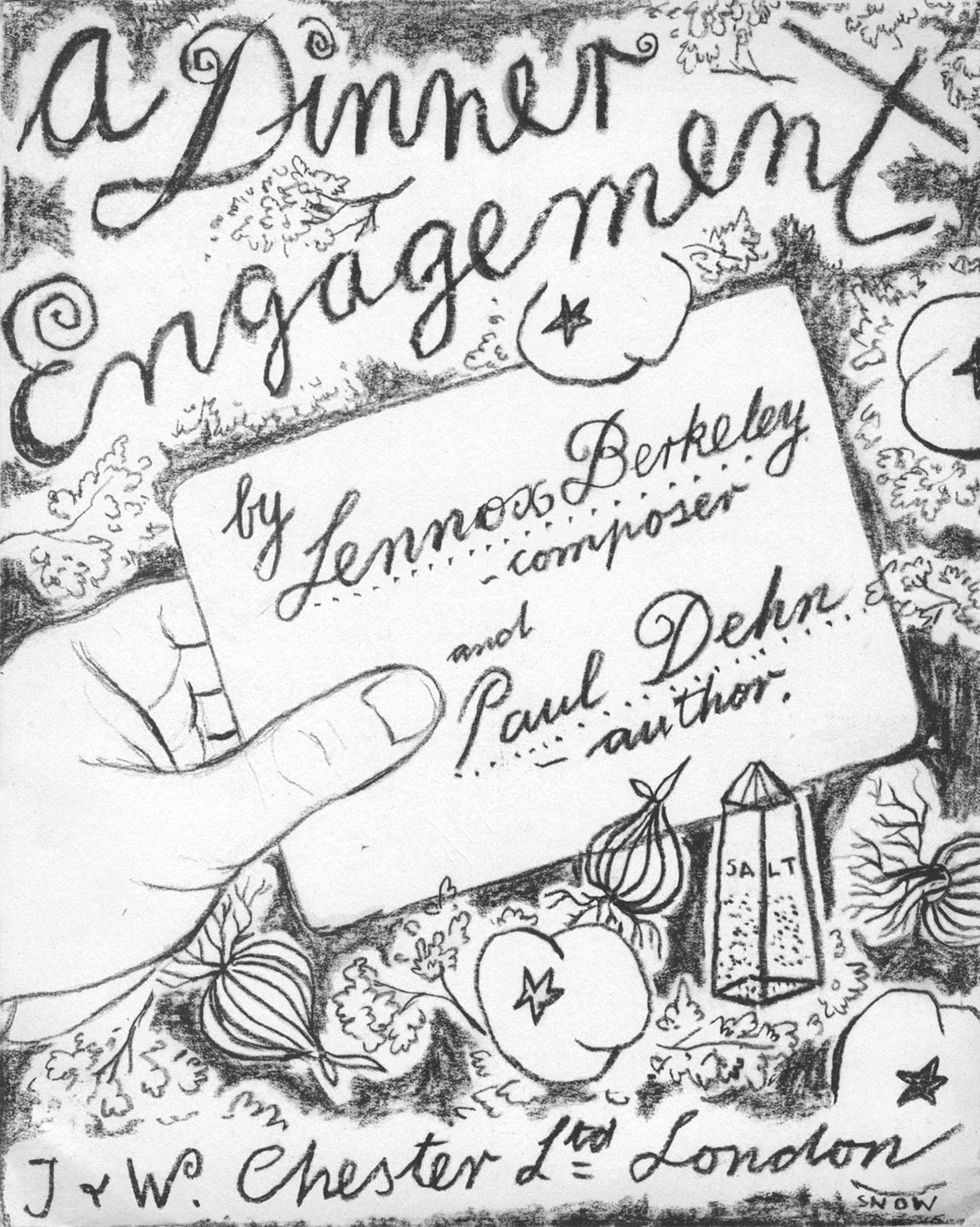

According to Dehn, A Dinner Engagement was conceived in 1954 ‘through a series of actual dinner engagements at Lennox Berkeley’s house and my own. On these occasions we always spoke glowingly of each other’s food, so that when the English Opera Group commissioned us to write a light one-act opera, it seemed proper that the action should be set in a kitchen.’

Twelve years later Dehn and Berkeley collaborated again on another one-act opera, Castaway, based on an episode in Homer’s Odyssey. The piece was intended to precede A Dinner Engagement in a double bill, but at its first performance by Britten’s English Opera Group in 1967 it was paired with Walton’s The Bear, for which Dehn had written a libretto based on the play by Chekhov. And it was not till 1983 that Berkeley’s two Dehn pieces were staged together, by students at Trinity College of Music.

A lifelong smoker, Paul Dehn died of lung cancer in 1976, aged only sixty-three.3 In an online appreciation, entitled Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Schreiber: The Unsung Achievement of Screenwriter Paul Dehn, the American arts journalist David Kipen writes, ‘Save The Taming of the Shrew, Dehn never wrote a script that did not begin or end in death. In the work of a writer as war-scarred as Dehn, death is rarely solitary. In Seven Days to Noon, he imperilled an entire city; in Goldfinger, half of Kentucky. In The Night of the Generals, Peter O’Toole orders the massacre of the surviving population of the Warsaw Ghetto. The “holy fallout” in Beneath the Planet of the Apes takes the whole planet with it.’

Like Paul Dehn himself, Kipen makes no exaggerated claims for these screenplays: ‘Dehn wasn’t the best screenwriter who ever lived. He wrote too few originals, and too often in collaboration, to claim anything of the kind’. But his scripts ‘suggest an intelligent, witty, morally engaged, cohesive sensibility’.4

In a brief entry in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, the military historian and travel writer, the late Raleigh Trevelyan, another friend of the Berkeleys, described Dehn as a serious thinker with a warm and romantic nature. ‘He delighted everyone with his entertaining manner and piano playing, and could put on a “good nightclub act”.’

Paul Dehn could also write highly effectively for the stage, and it is sad that he and Berkeley never collaborated on a third opera. But their friendship brought them much joy, which Dehn celebrated in a charming sonnet he wrote in 1971 on the occasion of the silver wedding of ‘Lennox-and-Freda – ever hyphenated till the journey ends’.