Phonographs, pianolas and Berkeley

Michael Boyd, an authority on the history and workings of the Pianola, considers the instruments and the repertoire which provided Berkeley’s gateway to music

Lennox Berkeley used to recall that his father, a retired naval officer, was passionately fond of music but had not been able to learn music as a boy, or even to hear very much. In an interview in 1974 he said that Captain Berkeley had ‘acquired a Pianola, with all kinds of rolls of classical music – Beethoven sonatas and arrangements of concertos – which I heard at a very early age on this machine. That was my introduction to music’.1

It is very easy, in our age of freely-available recorded and broadcast music, to overlook the simple fact that in the early 1900s there were only two means of enjoying ‘recorded’ music in the home: the Phonograph and the Pianola.

The Phonograph, invented by Thomas Edison in 1877, was conceived as a means of recording speech, and its cylinders had a capacity of two minutes’ duration on each one. This was doubled in 1908 with the introduction of the four-minute ‘Amberol’. Emile Berliner’s development of the flat disc (which we all now refer to as the ‘78’, played on a gramophone) again increased the available time per record, but the fundamental drawback remained – poor recording quality. With the benefit of hindsight, these early recordings are very poor indeed. This is hardly surprising given that they were recorded acoustically, with the performers being overshadowed by a vast horn, which captured their efforts and directed it to the needle that etched a groove in the master recording disc.

Piano performances fared particularly badly. In 1910, Arthur Rubinstein recorded Liszt’s Hungarian Rhapsody No 10 for the Polish label Favorit. The pianist was so displeased with the process, saying it made the piano sound ‘like a Banjo’, that he did not record for it again until the advent of the electric recording process in the mid-1920s.

The longevity of the 78 record and the gramophone (both lasted until circa 1960) has ensured their place in recent cultural history, and large numbers have survived.

The original Pianola was one of several such instruments that became available in the 1890s. The principle had its origins in the organette and similar instruments which used a roll of thick paper, perforated with holes representing the notes of the chosen piece of music, with bellows producing the ‘wind’ to sound the organ reeds. When a hole in the moving roll exposed a corresponding hole in the reading-bar, air was drawn in by the bellows and a reed sounded. The Jacquard weaving-loom and Charles Babbage’s Analytical Engine (the forerunner of the modern computer) also used the perforations on card or paper as a means of storing information.

The first Pianola (a trademark of The Aeolian Company of New York) appeared in 1898 in America, and a year later in Europe. It was placed in front of a piano, which it played by depressing the keys with felt-covered wooden fingers. Sixty-five notes of the piano were played (the lowest and highest octaves were omitted), though later models played the whole keyboard. The ‘Pianolist’ operated foot-treadles, as in a harmonium, producing a vacuum which closed a small bellows when instructed to do so by a perforation in the music roll. Each of the sixty-five key-pressing fingers had one such bellows operating it, controlled by valves linked to the holes in the roll-reading bar. The Pianolist’s hands were occupied with levers that controlled the tempo of the music, the sustain pedal of the piano (via a metal foot) and also the balance between melody and accompaniment. Thus the Pianolist was able to make an interpretation of the music roll.

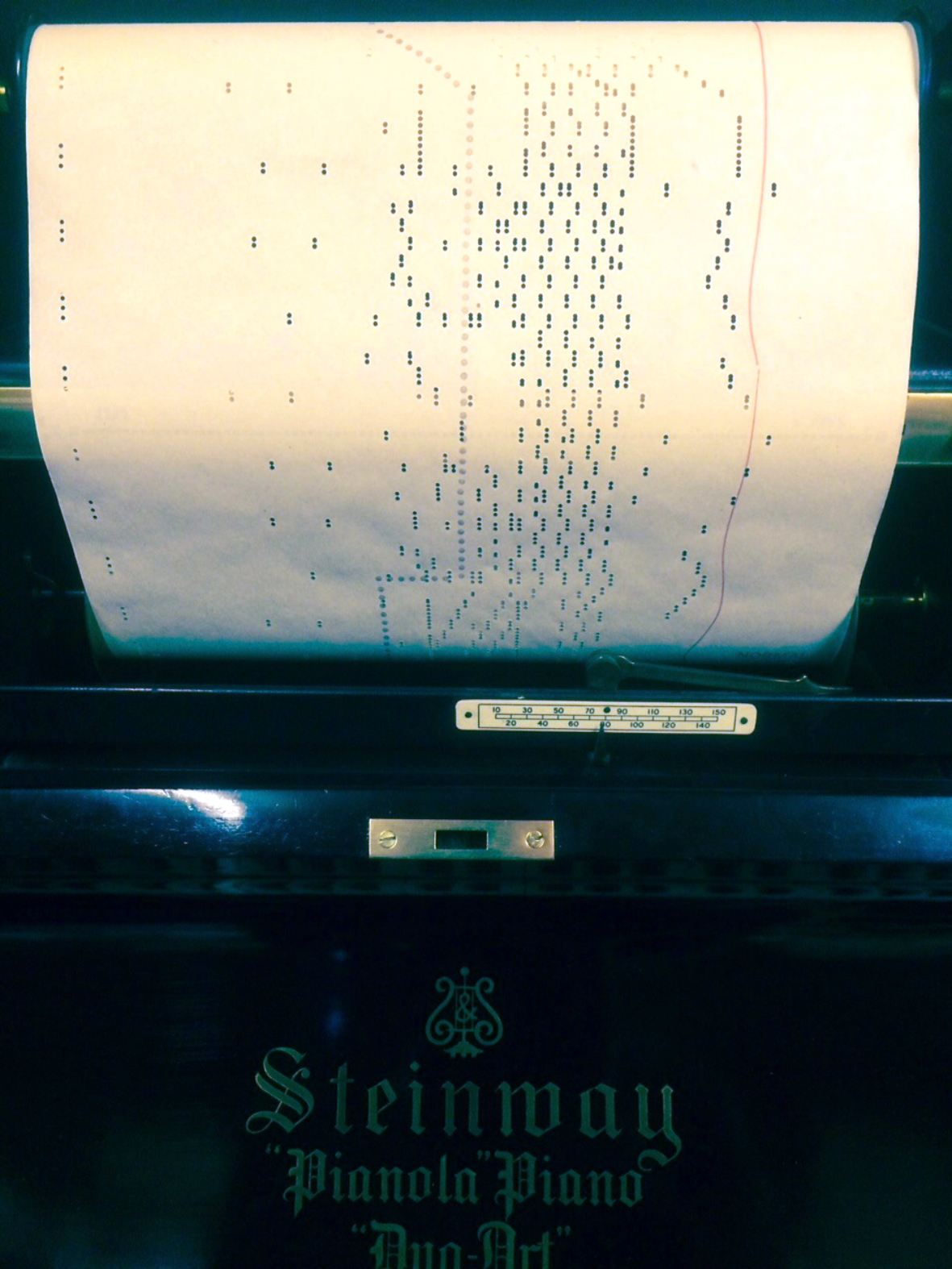

Despite its high price (£65 in 1902, or at least £6,300 now), the Pianola rapidly gained popularity around the world, and could be found in the salons and music-rooms of most royal families – Queen Victoria owned two, but it is not known whether she actually played either. By about 1905, the cabinet Pianola was beginning to be superseded by the Pianola piano, specially-made instruments that incorporated the pneumatic mechanism within them. Their development at once removed the often-heard complaint that the cabinet Pianola obstructed the use of the piano keyboard for hand-playing. It is these instruments that are commonly known as Pianolas nowadays.

The catalogue of music for the Pianola became, as the years went by, a weighty tome which embraced almost all genres and composers. The Beethoven sonatas that Lennox Berkeley mentions were the staple of most Pianolists’ roll libraries, together with the music of Chopin, Mendelssohn, Brahms, Gilbert & Sullivan et al, and the popular tunes of the day. The surviving piano rolls – and there are vast quantities of them – provide an accurate snapshot of the musical tastes of the time (and later times, for piano rolls are still being made today; production has never ceased in over a century). In those pre-World War 1 days, there was little appetite for Bach or anything earlier, nor for Mozart or Haydn, save for a few of the latter two composers’ symphonies arranged for four hands, and some other pieces.

By the end of the 1920s that situation had changed very little, but it is interesting to see how much twentieth century music had been transcribed on to piano rolls. Several composers had discovered the possibilities offered by a pianist with eighty-eight fingers – for that is, essentially, what a Pianola was. The list is an illustrious and lengthy one, notably including Stravinsky, Hindemith, Busoni, Casella, Bax, Milhaud, Eugene Goossens, and Percy Grainger. Stravinsky, Hindemith and Casella wrote with the Pianola in mind, and used its unique capabilities to the full. For Busoni, Goossens and Grainger, existing compositions were arranged for the instrument. Stravinsky’s Étude pour Pianola, written in 1917, is unplayable by two or more pianists at one piano and is known today in the composer’s later orchestration as ‘Madrid’ in his Quatre Études pour Orchestre (Stravinsky boasted to Ernest Ansermet that his Étude was ‘the first in the world’). Percy Grainger, perhaps unsurprisingly, arranged his Shepherd’s Hey for Pianola in 1914. Although essentially the same in style, duration and dynamics as the piano solo and various instrumental arrangements, the Pianola roll version contains occasional ‘outbursts’ which range across the entire keyboard at once and are not conceived from a pianistic point of view. Grainger also arranged (or ‘dished up’, as he would have said) Molly on the Shore at the same time, but this is a much more restrained affair. In both arrangements, Grainger treats the keyboard in a freely orchestral manner, devoid of digital constraints.

Some of Lennox Berkeley’s circle of French friends each had very different encounters with the Pianola. Francis Poulenc got as far as announcing, in 1921, that he was composing Trois études pour Pianola. Whether or not this was suggested to him by Stravinsky, nothing seems to have resulted; more’s the pity. Maurice Ravel’s strange and uncharacteristic Frontispice of 1918 (for two pianos, five hands) has been attributed to the series of commissions made by The Aeolian Company in 1917-18 which resulted in the Stravinsky Étude and pieces by Casella, Goossens, Bax and others. Ravel had agreed to contribute, it seems, but the absence of a piece by him in the final series of rolls may be explained by Aeolian’s dissatisfaction with his submission – Frontispice perhaps? Darius Milhaud’s one-act ballet La bien-aimée was an arrangement of music by Schubert and Liszt for Pleyela (the piano maker Pleyel’s brand of player piano or Pianola) and orchestra. It had the misfortune of receiving its première in the same week (in November 1928) as Ravel’s Bolero which eclipsed it. It is also very likely that the difficulties of synchronising the Pleyela with the orchestra, and the decline in popularity of the instrument, also contributed to its being soon forgotten. Milhaud re-orchestrated it some years later, omitting the Pleyela, but the original score and orchestral parts (and presumably the rolls) were destroyed in a fire at the publisher’s offices in the 1950s, thus preventing this writer and others from resurrecting it. Arthur Honegger’s ‘Pacific 231’ of 1923, the first of his three Symphonic Movements, was issued by Pleyela in a piano-roll transcription of the piano duet score, as was Milhaud’s Le Boeuf sur le toit, though the latter is an ‘edited highlights’ version by the composer.

Pacific 231’ and Le Boeuf sur le toit and countless other transcriptions were, for the most part, no more or less than their piano originals and had to be interpreted using the controls previously mentioned, and judicious use of the foot-treadles. Some rolls were ‘hand-played’, that is to say that the master-roll was created in the same way as a pianist (or pianists) played a recording piano. These rolls ensured that the correct tempi (and variations thereof) were automatically reproduced if the roll was played at the speed as indicated at the start. The correct dynamic levels still had to be provided by the Pianolist. Many rolls had perforations that operated an automatic sustain-pedal mechanism, and others that enabled the melody to stand out above the accompaniment if the instrument was suitably equipped. There was even a ‘Reproducing Piano’ that used a hand-played roll that had the entire performance of a famous pianist encoded in it – including the dynamic strength of each note or chord, and the sustain and soft pedal operation. These complex instruments would reproduce the performance with remarkable fidelity, and even today a properly-restored Duo-Art, Ampico or Welte reproducing piano can give astonishing results. They were powered by an electrically-driven vacuum pump, and were aimed squarely at the wealthy and famous. Most pianists of note in the period from about 1910 to 1930 recorded for them.

The majority of Pianolists, such as Lennox’s father, would probably have found the Stravinsky Étude or Casella’s Trois Pièces pour Pianola decidedly beyond the pale. The ‘Beethoven Sonatas and arrangements of Concertos’ and all the other unspecified rolls in Hastings Berkeley’s collection provided a musical stimulus for the young Lennox, and he was not alone in being able, in later life, to credit the Pianola in this way – Gershwin, Poulenc, John Lill, Jools Holland and many more have acknowledged the influence that this unique instrument had on their musical awakening.