Performing and recording the Stabat Mater

Lennox Berkeley Society president Petroc Trelawny and conductor David Wordsworth explain a highly ambitious project to revive, perform and record Lennox Berkeley’s masterpiece, the ‘Stabat Mater’.

It was the Society’s most ambitious undertaking: a grand project to revive, perform and record Lennox Berkeley’s masterpiece, the Stabat Mater. Two years elapsed between informal discussions at a Society committee meeting and the first performance, with some major hurdles presented along the way.

It was not the Society’s first grand projet – nearly a decade ago we recorded a disc of Lennox’s songs, performed by tenor James Gilchrist and pianist Anna Tilbrook. At the time it seemed like an overly ambitious idea. But now we found ourselves working not with two but nineteen professional musicians; simply finding space in their schedules was challenging enough.

David Wordsworth, my predecessor as Chairman, explains in the interview below why he wanted to record the Stabat Mater. Written for Britten’s English Opera Group, it calls for a very particular set of voices. Should we cast six solo singers individually, or go for an already established group? As David explains, it was composer Gabriel Jackson who suggested the Marian Consort. Rory McCleery, its director, showed immediate enthusiasm when we met him late in 2014. The highly talented Berkeley Ensemble, who already have a close relationship with Lennox’s music and the Society, were the obvious source of instrumentalists.

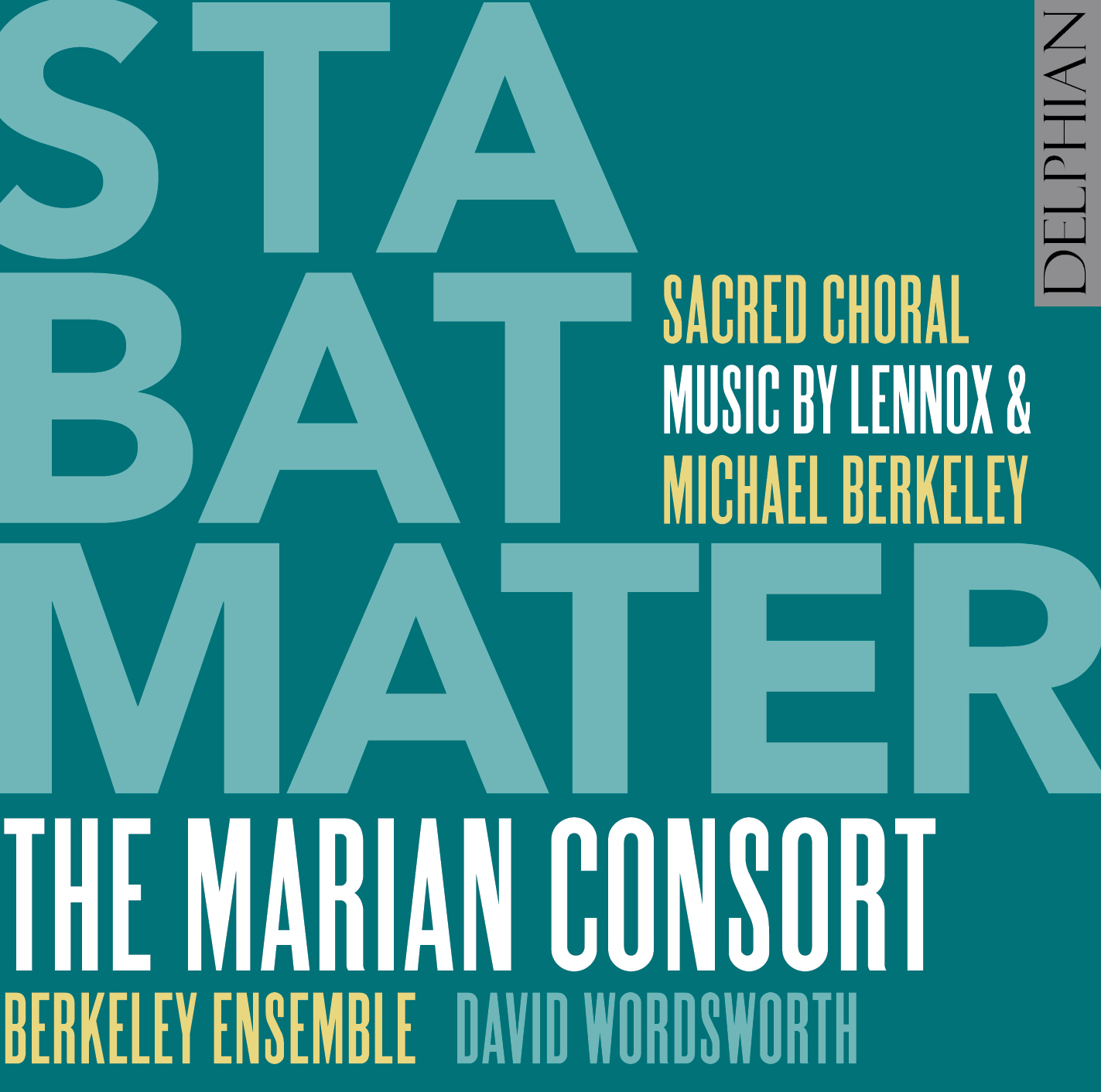

Two record labels were keen to make the CD recording, and, after some discussion, it became clear that Delphian was the perfect home for the work. The company’s founder, Paul Baxter, was highly supportive from the start, convinced that this was the right moment to bring the Stabat Mater off the shelf, and to present it to a new audience.

The Cheltenham Festival were the first to ask us to perform Stabat Mater on stage. Then Aldeburgh Music came on board, its director Roger Wright determined that a work with such close connections to Benjamin Britten should ‘come home’. Michael Berkeley then suggested Spitalfields, and within a matter of days it was on board too. Generally music festivals like to have exclusivity when it comes to performance – but understanding the unique nature of this work, Cheltenham, Aldeburgh, and Spitalfields all agreed to host it within the same season. Aldeburgh suggested we might rehearse and record in the Britten Studio, an acoustically fine venue set at the heart of the bustling Snape Maltings site.

Just one issue was left – how to finance the project. The costs – artists’ fees, music hire, rehearsal venues, accommodation and expenses – appeared daunting when presented on one of our Treasurer’s all-too-clear spreadsheets. But, bit by bit, the funding came in – from the three festivals, charitable trusts, individual members, friends and supporters, many of whom asked to remain anonymous.

On a bright, cold Good Friday, Blythburgh Church was packed for our first performance – on the home ground of the composer who commissioned the work seventy years earlier. Over the following days the musicians recorded the work, carefully marshalled by producer Paul Baxter, who demanded the highest standards of his assembled cast – and, achieving them, responded with warm praise. On 7 June, the project came to London, where the performance at St Leonard’s, Shoreditch, was recorded for broadcast by BBC Radio 3; a matinée at the Pittville Pump Room in Cheltenham on 17 July concluded the project.

As well as the Stabat Mater, the CD also includes Lennox’s Mass for Five Voices, written for the Choir of Westminster Cathedral, and his motet Judica Me, along with his son Michael Berkeley’s rapturous meditation on Monteverdi and Purcell, Touch Light, for soprano and counter-tenor soloists.

Already the recording and the live performances of the Stabat Mater have brought fresh interest for the work. Paul Driver in The Sunday Times described it as ‘downright astonishing’. Classical Music made it their Editor’s Choice, calling it ‘an inspired and moving major work … by turns, eerie, poignant and powerful’. The Guardian found it had ‘a solemn sort of neo-classicism, all jagged-edged mysticism and glimmering triads’, concluding ‘There’s earnest beauty in it’. Music Web International introduced the recording as a very important presentation of ‘an unjustly neglected English vocal work of the highest quality’.

Bringing this project to fruition has been an extraordinary achievement by the Society; the calm faith and patience of the Committee (in the face of sometimes alarming budgets) has now been rewarded; the dedication of the players of the Berkeley Ensemble and singers of the Marian Consort deserves rich praise, as does David Wordsworth’s dogged determination to bring the Berkeley Stabat Mater back to life.

An ardent champion of Lennox Berkeley’s music, David Wordsworth has long nurtured an ambition to record the ‘Stabat Mater’. In an interview with Katherine Cooper on the website ‘Presto Classical’, he spoke about the challenges posed by this unusual and demanding work, and about Berkeley’s evolution as a composer of sacred music.

KATHERINE COOPER: Why do you think the Stabat Mater has been performed so rarely?

DAVID WORDSWORTH: I think part of the problem is that you need six singers who are good soloists but who are also able to blend with each other, plus twelve superb instrumentalists – it’s not a song-cycle, it’s not really a choral piece… It kind of falls into a little hole in the middle somewhere. The vocal parts are on the one hand quite operatic, quite dramatic, but on the other they’re very straight and focused. It’s a very hard piece to programme, I think, partly because of the quality of singers and instrumentalists it requires – also what does one programme with it? Perhaps also because Berkeley is one of those composers who’s fallen through the cracks a little bit – he’s perhaps not as well-known as Britten or Walton, but he should be, he has a very particular voice – and a piece like the Stabat Mater shows a rather more passionate and intense side of his musical character. It really is a major statement.

KC: You’ve wanted to record this for many years: how did you hit upon the Marians as being the group you needed?

DW: Well I can’t really take credit for that – the suggestion actually came from my friend, the composer Gabriel Jackson. He knew that I very much wanted to do the piece and suggested that I listen to the Marians. I first conducted it something like twenty-six years ago, in a memorial concert for Lennox in 1990, at St Giles, Cripplegate. I didn’t know the piece at all, but when I got the score it completely knocked me out: I thought it was a masterpiece, so I’ve been itching to record it for years. And then I became chairman of the Lennox Berkeley Society, and they were keen to record as well, but I hesitated because I wanted the right kind of voice. It was written for the English Opera Group, to go on tour with Albert Herring and The Rape of Lucretia, and the voices and instruments match the scoring for those pieces: they were the resources on offer, and so Britten asked Lennox to work with that. I wasn’t so keen on putting together a kind of random group of soloists for the recording.

KC: Was there also an element of wanting ‘cleaner’ voices?

DW: I suppose so, yes – the piece is in a way a kind of conducted chamber music that requires the singers and instrumentalists to really blend. Now I’m not saying that more conventional soloists wouldn’t do that, but it’s just more natural for a vocal ensemble, that work together a great deal and sing a lot of early music as well as more recent work. This of course means that the seventh movement, which was originally written for a female voice, is now sung by the counter-tenor Rory McCleery (Director of the Marian Consort), but he does it wonderfully and it really works. I like to think that Lennox would have approved of this.

KC: Are there plans to record any other sacred works – I believe there’s a Jonah, for instance?

DW: Gosh, I’d love to. There is indeed a Jonah, which is a large-scale pre-war oratorio – a vocal score exists, but I think the orchestral material’s been lost. Lennox was a devout Roman Catholic, and I think the sacred music speaks particularly strongly. Quite a lot has been recorded already, particularly the church music, but there are some gaps, an early choral/orchestral piece called Domini est Terra, for example.

KC: Do you feel that Britten’s influence is apparent in the Stabat Mater (and indeed throughout Lennox’s career)?

DW: I think it’s certainly there, but it became less obvious when Britten went to America and Lennox was able to become his own man a little bit more. I think the influence of Britten is fairly slight in the Stabat Mater – there’s more Stravinsky I think, and even a little bit of Poulenc, but I think it’s completely individual as well. Lennox, like all good composers, cheerfully pilfers from lots of sources, but the important thing is that it comes out sounding like Lennox Berkeley. Particularly in the more lyrical movements, I think there’s a very personal melodic voice – he really sounds like nobody else.

KC: The disc includes some of Michael Berkeley’s work as well: how much influence do you think Lennox had on Michael’s choral writing, or are they very distinct voices?

DW: Michael, I think, was much more influenced by later twentieth-century developments, though a love for the voice comes through, and there is definitely a lyrical side to Michael’s language.

KC: How much had Lennox’s style altered between the Stabat Mater and the later works on the disc?

DW: Well, he went through a period in the late fifties and early sixties where he felt that everybody around him was experimenting with things like twelve-tone technique, but I don’t think he was ever really convinced it was for him. There are certain pieces that use the twelve-tone row, but it’s not strict in any way. It is true to say that the Mass For Five Voices is a little bit more austere – and it comes from that period [1964], but it is still remarkably beautiful and still recognisably by the same composer. He was engaged, certainly, with developments in music, but ultimately he had his own voice and he wanted to develop that rather than to experiment for the sake of experimenting.