Robin Tritschler on Lennox Berkeley’s ‘Songs of the Half-Light’

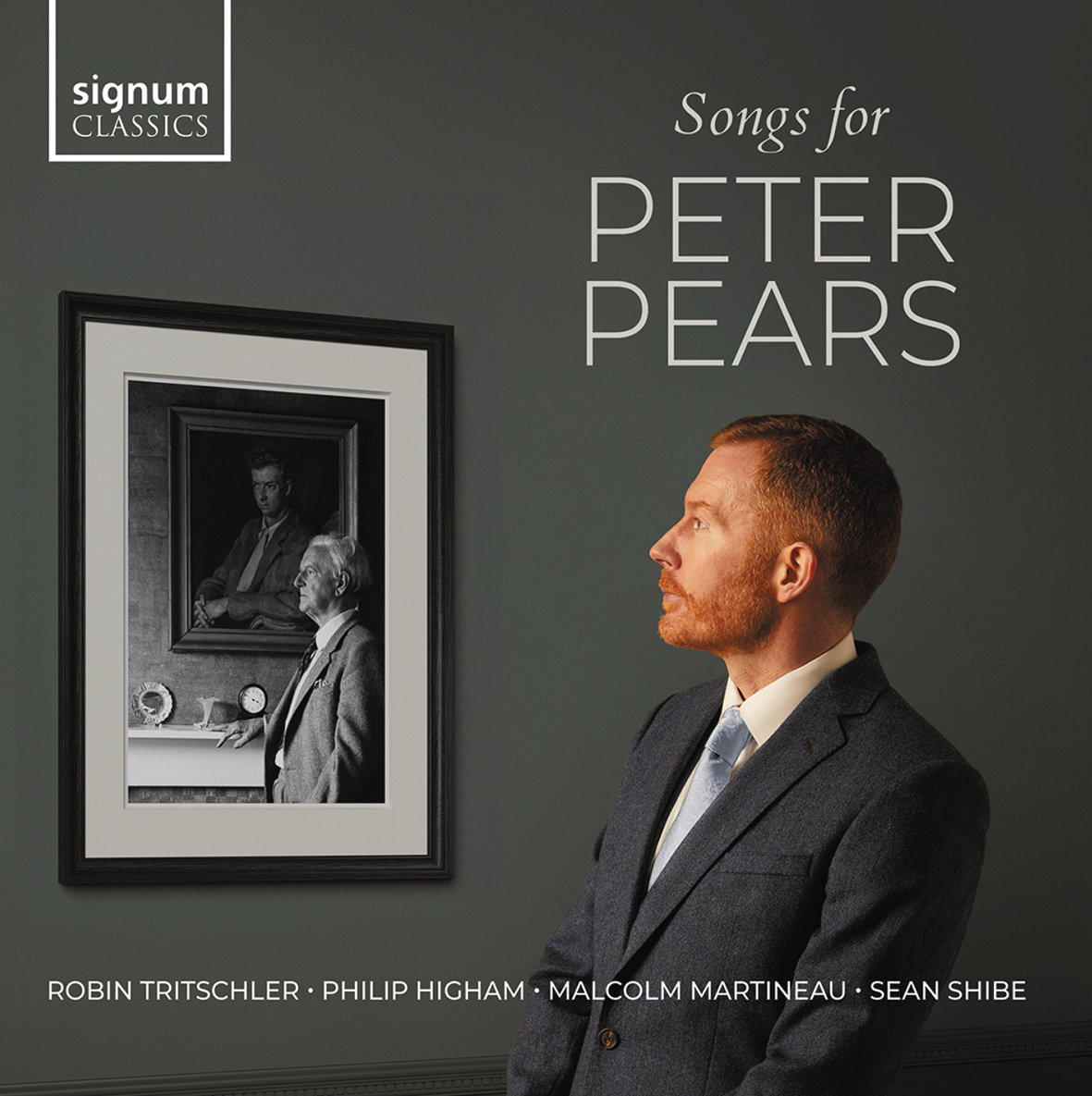

Tenor Robin Tritschler writes about Berkeley’s de la Mare setting, ‘Songs of the Half-Light’, which he has recorded with guitarist Sean Shibe.

For the 1965 Aldeburgh Festival Peter Pears commissioned Berkeley to compose songs with guitar accompaniment. Berkeley chose poems by Walter de La Mare (1873–1956), a poet he had set twenty years before.

Like his earlier choice of Housman, Berkeley appears to be out of step with the time’s modern thinking. De la Mare, who often wrote of the innocence of children and the desire to return to that state, had been dismissed by the modernists who thought his verse structures and themes at odds with their movement and response to World War 1 (and by now WW2). So for Berkeley this was a personal choice.

Berkeley always had an individual approach to his music. He rejected the English nationalism of Vaughan Williams and the post-Romantic style. Instead he trod a line between his English predecessors and the tonal experiments of the Second Viennese School. As Peter Dickinson puts it, in The Music of Lennox Berkeley, ‘His musical inheritance, unpretentiously European, finds its centre of gravity somewhere in the English Channel.’

Pears gave the first performance of the songs on 22nd June 1965 with guitarist Julian Bream.

Rachel

The poem features three of de la Mare’s favoured topics; innocence, the desire for childhood, and ageing. A little boy is entranced by Rachel’s singing and her movements over the piano. But he also sees the darkness of her thoughts. Berkeley uses the long guitar theme economically throughout the song as it plays Rachel’s music. Its distinct rhythm almost hypnotises the boy, while the constant alternation between the melodic and harmonic minor unsettles Rachel’s sense of reality. The vocal line is not Rachel’s, rather a third person observing the scene. Only when the interloper speaks of memory does the voice mimic the guitar. The protracted and legato melisma inspire their own examination of past experience.

Full Moon

Here is a lunar liaison of a most delicate nature beautifully described in words and music. Berkeley’s opening theme introduces the listener to a gentle moon. The up beat, a written-out strum which would sound like an ornament in a faster tempo, portrays the slow but constant movement of the moonlight which envelops objects in the room, until finally vanishing. Dick is undisturbed by the fascinating and welcome visitor. Otherwise, why would he leave the curtains open?

All that’s past

De la Mare offers a grim reality in this poem. Nature exists in a cycle of replenishment; the roses entangle themselves with their surroundings and bud each year, the snows and rain maintain the winding river as it winds through the landscape. Those have seen eons pass and have grown wiser as result. Men alone age. Our initial young dreams may be the same as those of our predecessors but as our own time passes our thoughts develop individually. They are barely a whisper to the world. Only in death do we become an eternal part of nature. Berkeley seems to want to race through this tale. Like nature his music does not settle for a moment. The guitar theme tugs back and forth, the ostinato mingling major and minor modes as it surges on. The inevitability of this unremitting music strangely makes the realisation of our own temporary state easier to bear.

The Moth

This song highlights for me why Berkeley is a brilliant composer of vocal music. The simplicity of the idea; the theme and its execution combine to make an immensely satisfying song to perform and to hear. The moth’s efforts are heard as it rages towards the light. Berkeley’s accompaniment perfectly captures the moth’s hectic path; frantic to our ears (and eyes when you see the score) but light and delicate for the moth. However the wonder for me is how the same music also seems to describe the creature; its furry wings and feathery eyes, its weightlessness, its determination.

The Fleeting

If Berkeley’s whooshing wind were any more powerful the point of the poem would be obliterated. But the composer judged the pitch, length and speed of the underpowered wind to perfection. Now the eerie silence de la Mare describes can be discerned among the distant gusts. In this placid moment the movement of the stars is perceptible and the enormity of the universe, and our minuscule role in it, can be fully appreciated.