Lennox Berkeley (1903–1989)

The late Master of the Queen’s Music, Malcolm Williamson, once wrote that if quality meant more than fame, then Lennox Berkeley should be placed in a position of the highest eminence. In an obituary notice in 1990, he called for a major revival of the Berkeley repertoire, saying that ‘it needs to be played and heard — all of it, and many times.’

The surprising thing about the music of Lennox Berkeley is that there is so much of it. Though a notoriously painstaking and meticulous craftsman, he produced — in a creative life of about 65 years — no fewer than 226 works, including fine examples of music for the theatre, the concert hall, church and home. There are four symphonies; concertos for cello, flute, guitar, piano and violin; string quartets; piano pieces; four operas, a ballet, film and incidental music; Mass settings and other sacred music; and songs.

Berkeley’s special gift lay in writing music that rings with the truth of his own personal voice. He found that voice and learned to trust its individuality under the magisterial influence of the great French composition teacher Nadia Boulanger, to whom he had been introduced by Maurice Ravel on coming down from Oxford in 1926. It’s no coincidence that he should have found his faith as a Roman Catholic at the same time, and even considered becoming a priest. From then till his final illness he dedicated himself to writing music that expresses, in his own inimitable way, his personal vision of life and the God who created it.

With its hallmarks of stylishness, clarity and economy, and a certain bitter-sweet tunefulness, Berkeley’s music is instantly recognisable. Some of it may, at first meeting, seem modest, gentle and charming — like the man himself. But a further acquaintance reveals — as it did with Lennox himself — hidden depths of resolution, wisdom and purposefulness. And now and again, as the critic Edward Lockspeiser once pointed out, ‘some beautiful little flower of melody unexpectedly blossoms out, and this seems to be the true Berkeley.’

Lennox Berkeley was born at Sunningwell Plains, Boars Hill, near Oxford in 1903. His father, Hastings Berkeley, was a naval officer, amateur mathematician and the radical author of some recondite works of scholarship; his mother was a daughter of Sir James Harris, British Consul for Monaco, and a German aristocrat. The paternal grandparents were George Lennox Rawdon, 7th Earl of Berkeley, and Cécile Drummond de Melfort (descended from the French Ducs de Melfort and the Scottish Earls of Perth and of Seaforth). If George and Cécile had been free to arrange the timing of their marriage more conventionally, Lennox, in due course, would have inherited the earldom and Berkeley Castle — and we might never have had his music. But they couldn’t marry till after the birth of the second son because the young Cécile was already married to an elderly admiral infamous for causing mutinies, so Lennox’s father and uncle were born out of wedlock, and the third son, Randal, became the last earl. That George, Lord Berkeley turned out to be an inveterate gambler and an undischarged bankrupt cast a long shadow over the lives of all three of his sons and even over the next generation.

Lennox Berkeley was introduced to music by his father’s pianola rolls, by a godmother who had studied singing in Paris, and by an aunt who was a salon composer. Educated at the Dragon School in Oxford, Gresham’s at Holt in Norfolk (where he was followed by W.H.Auden and Benjamin Britten), and St. George’s School, Harpenden (where one of his first compositions was performed), Berkeley went up to Merton College, Oxford, in 1922 to read modern languages. He had, at that time, no intention of making music his profession, although he took some organ lessons from W.H. Harris and Henry Ley, and continued to compose. (And even though he wasn’t a stereotypical hearty, he also coxed a victorious Merton eight.)

The meeting with Ravel in London in 1926 was a watershed. Impressed by Berkeley’s gift for melody and harmony, Ravel was in no doubt that the young man’s future lay with music — and that Boulanger should be the teacher to forge the steel of his talent. Berkeley rose to the challenge and, with an undistinguished B.A., set off for France. He soon became a favourite of the godlike ‘Mademoiselle’, and stayed in Paris till 1932, studying counterpoint, developing his own unique musical language, and meeting many of the great figures of twentieth-century music including Stravinsky, Fauré, Francaix and Poulenc.

For nearly four years, after leaving Paris, he lived on the Riviera, looking after his ailing parents, and enjoying a glamorous social life — of tennis and golf, parties and concerts — as the friend and neighbour of Somerset Maugham at Cap Ferrat.

In 1936, after the death of his mother, he went to Barcelona for the annual festival of the International Society for Contemporary Music, and there met Benjamin Britten, with whom he collaborated on Mont Juic, a joint composition based on Catalan folk dances. For a time the two young men shared a mill at Snape in Suffolk till, on the outbreak of war, Britten went to America with a new friend, Peter Pears. Berkeley stayed on in England, spending the summer of the Battle of Britain composing, in an eccentric ménage in Gloucestershire, with, amongst others, Dylan and Caitlin Thomas, Humphrey Searle and William Glock. Immediately afterwards he volunteered for war service with the RAF, but was rejected for health reasons, whereupon he joined the BBC as an orchestral programme builder, based, at first in Bedford, and then in London. Throughout the Blitz he served as a volunteer air-raid warden in London.

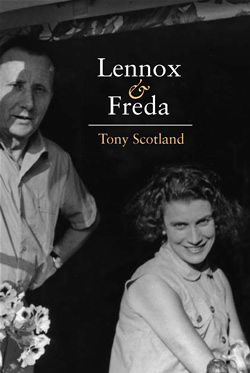

In 1946, at the age of 43, he married his secretary at the BBC, Freda Bernstein, the orphaned daughter of a Jewish merchant who had fled the pogroms of his native Lithuania (then part of Russian Poland), settled in Merthyr Tydfil selling clothes in around the populous coalfields of Merthyr Tydfil, and ultimately made his fortune as a boot dealer and landlord in Cardiff. The alchemy of Lennox and Freda created a conspicuously happy partnership that produced three sons, and radiated a celebrated warmth to a large circle of friends.

Earlier that same year Berkeley left the BBC to concentrate on writing music, and to take up a post as professor of composition at the Royal Academy of Music. He remained at the Academy till 1968, nursing two generations of diverse and idiosyncratic talents: among them David Bedford, Sir Richard Rodney Bennett, Professor Peter Dickinson, Brian Ferneyhough, Sir John Manduell (the Society’s President), Nicholas Maw and Sir John Tavener.

Knighted in 1974, Berkeley was president of the Composers’ Guild, the Performing Right Society, the British Music Society and the Cheltenham Festival of Music, and Master of the Musicians’ Company. These public honours were at odds with his essentially private nature, which was more comfortable with reticence than rhetoric; indeed understatement may well have limited his wider appeal.

Moderation is hardly the keynote of that handful of Berkeley’s works which have become classics, including Serenade for Strings, Divertimento in B Flat, the one-act opera A Dinner Engagement, the Missa Brevis (dedicated to his two elder sons, Michael and Julian, and the other boys of Westminster Cathedral Choir who first performed it in 1960), the psalm setting The Lord is my Shepherd and Four Poems of St. Teresa of Avila for contralto and strings (written for Kathleen Ferrier in 1947). A number of Berkeley’s smaller pieces are similarly popular, including Six Preludes for piano, the Sonatina for treble recorder (or flute) and piano, and several songs — for example Ode du premier jour de mai. But some works have disappeared from the repertoire — among them the Symphony No 1, the three-act opera Nelson, the one-act Bible opera Ruth and the two piano concertos (one of them for two pianos).

All the music is polished, thoughtful, and, in its quiet but sure way, passionate. Much of it is beautiful, and some is unquestionably of lasting importance. When he died in 1989, after suffering from Alzheimer’s disease, Lennox Berkeley left many treasures still relatively unexplored. Unearthing these — and re-discovering the rest of his work — will be both moving and exhilarating.